The Henry Jackson Society, a neo-conservative British think-tank, has issued a new report harshly condemning Saudi Arabia for funding religious extremism in the West.

The report, so far not accessible to the public, has been submitted to the British Prime Minister, Theresa May. The Henry Jackson Society speaks of a “clear and growing link” between jihadist terrorism and Saudi money and support.1

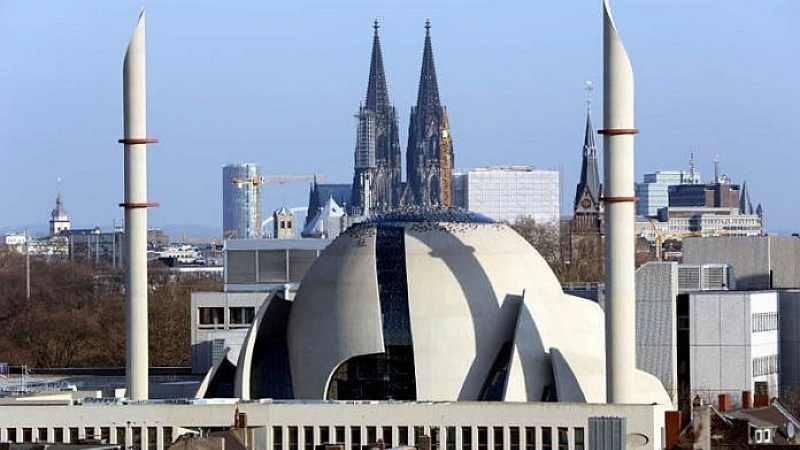

Saudi religious activism in Germany

The Society’s findings have been eagerly taken up abroad as well, including in Germany. Germany, too, has witnessed repeated public debates on the role of Gulf money in supporting Islamist extremism. In late 2016, a German intelligence report claimed that Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Kuwait were supporting radical Islamists in the country.

Speaking to Deutsche Welle, Susanne Schröter, anthropologist and professor of Islamic Studies at the University of Frankfurt, said that she was not at all surprised by the findings ofthe Henry Jackson Society. She asserted that Saudi Wahhabism was largely similar to the ideology of the so-called “Islamic State” and that the post-1979 Saudi attempts at exporting a rigid and violent understanding of religion had been a great success.2

Long-standing accusations

In and of itself, none of these allegations are new. In journalistic as well as in academic discourse, it is commonplace to assert that the oil boom (al-tafra) allowed the Saudi Wahhabi establishment to go on such a spending spree that it managed to obtain what had eluded religious reformers for more than a thousand years – namely global hegemony over the Islamic nation (umma).

To be sure, this perspective has some valuable insights to offer: it is indeed true that the Saudi clerical and political establishments have sought to rely on the exportation of religious doctrine as a way of buttressing their own agendas. Nor can it be denied that individuals socialised in Saudi or Saudi-funded institutions have been amongst the proponents and perpetrators of jihadi violence.

Saudi money, Saudi control?

Yet what those pointing to the “Saudi connection” often fail to make explicit are the ways in which Saudi largesse does its work. More specifically, one might wonder about the extent to which Saudi monetary transfers to various religious causes and institutions actually lead to Saudi control. And here the Saudi track record does not look particularly good.

At almost every historical juncture – starting from the 1990/91 Gulf War, through the internal Saudi unrest of the 1990s and the wave of terrorist attacks of the early to mid-2000s, to the engagement of the Saudi state in Syria – the Islamist and jihadist scene, supposedly marked by the adhesion to Saudi dogma, in fact abandoned the Kingdom and worked on the side of the Kingdom’s enemies.

Local adaptations

In some ways, this should not come as a surprise: to many outside observers (Islamists and even jihadists included), the Saudi regime appears simply too corrupt and sclerotic to be worthy of sustained loyalty. And even where such questions of political allegiance take the back seat, Salafi preachers – even those educated in a Saudi setting – have always been forced to adjust their teachings to local circumstances.

To give but one rather colourful example in this regard, in order to make to with the gender norms prevalent in the country, Germany’s most well-known Salafi Pierre Vogel – touched upon in the abovementioned interview with professor Schröter – has stated that in the German context it is licit for women to have a prominent role as public speakers at gender-mixed Salafi events.

According to Vogel, haja (‘necessity’) in this case nullifies the prohibition on gender-mixing imposed by the doctrine of sadd al-dhara’i’ (‘blocking of the means’). Needless to say, this striking doctrinal innovation would certainly be regarded with a high degree of suspicion by Saudi scholars.3

The attractiveness of the ‘Salafi’ creed

In her interview, Schröter discusses the proximity of various figures of the German Islamic associational scene to Saudi money and religious orthodoxy. Yet the precise workings of the stipulated causality are left unclear: how is it that generous financial backing from the Gulf leads to the radicalisation of Muslims in the West? And on which terms?

The most glaring lacuna in this respect is the failure to provide an account of the sources of the attractiveness of a Salafised religiosity: why is it that this particular religious form should be seen as appealing by a small but considerable number of European Muslims? Indeed, the Islamic tradition would offer a host of other spiritual paths, some of whom may also be deemed “radical” (though not necessarily violent).

More complex questions

This is not to deny the overwhelmingly illiberal nature of Saudi-sponsored religiosity. Nor is it to exclude that Saudi support may play a role in spreading a particularly rigid, Wahhabi-tinged religious thought and practice. What appears necessary to scrutinise, however, are the ways in which a Wahhabi-Salafi creed resonates with the particular conditions of Muslim life in Germany and Europe.

This means going beyond pointing to Saudi funding of mosques and preachers. It means starting to ask a host of questions that may be far more difficult to answer, and the answers to which might be far more unsettling.

Sources

http://www.dw.com/en/saudi-arabia-exports-extremism-to-many-countries-including-germany-study-says/a-39618920 ↩

See Wiedl, Nina (2014). “Geschichte des Salafismus in Deutschland”. In Hazim Fouad and Behnam T. Said (eds.), Salafismus: Auf der Suche nach dem wahren Islam. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder. ↩