For many decades after the arrival of Muslim ‘guest workers’ from Turkey, Morocco, and other Muslim-majority countries, German authorities were happy to outsource the provision of religious services to Imams and preachers sent by the Muslim immigrants’ countries of origin. Since the Muslim workforce would ultimately return home, it was unnecessary and even counterproductive to grant Islamic religiosity a permanent presence – or so the reasoning went.

‘Domesticating’ Islam

It was only around the turn of the millennium that perceptions changed. After the events of September 11, 2001, authorities took a securitised perspective on Islam. Fears about the uncontrolled flourishing of a radical underground religious scene appeared to call for the creation of more transparent structures of Islamic learning.

Members of the Muslim community also began to voice a critique of the prevailing arrangement: they bemoaned the fact that Imams knew little about life in Germany or Western Europe and could not provide guidance on many issues that mattered to believers, and especially to younger audiences.1

Establing new chairs

In 2011, then, the German government – taking cues from the country’s ongoing Islamkonferenz, an (often controversial) forum bringing together state authorities and various Muslim figures and organisations – decided to fund the creation of several university departments of Islamic theology.

Subsequently, several university chairs were established – at Tübingen, Frankfurt/Gießen, Münster, Osnabrück, and Erlangen/Nuremberg. State funding, initially granted for five years, has since been renewed. Overall, the Ministry for Education and Research has spent € 36 million on these new faculties.2

Training school teachers

Yet while the formation of Imams for Germany’s mosques has been on the agenda of these university departments, their main focus has been the training of teachers for Islamic religious education classes in public schools.

The understanding of secularism anchored in Germany’s constitution is not marked by a laic attempt to cleave apart public and religious life in a stringent manner. Instead, the German ethos is one of cooperation of state and religious bodies in the public sphere. Consequently, the country’s public schools offer confessional courses in religious education adapted to the pupils’ faith.

Expanding employment opportunities for graduates

Many of Germany’s 16 federal states – who are each individually responsible for their own educational sectors – rapidly expanded their offerings of Islamic religious education in the 2000s. Ever since, they have been in dire need of skilled teaching personnel to fill vacant positions.3

Of the currently 2,000 students enrolled in degree courses in Islamic theology, most will seek employment as secondary school teachers. Others might staff the ranks of Germany’s expanding Islamic social welfare sector. Confessional institutions run by large Catholic and Protestant charity organisations play a pre-eminent role in various fields of pastoral care, including in care for the elderly. Now, with the ‘guest worker’ generations ageing, there is a growing demand for Islamic offers in this domain.4

No progress on the formation of Imams

What the centres for Islamic theology have not accomplished so far, however, is to foster a new generation of Imams that could preach in German mosques. In fact, students themselves express little desire to pursue this career – a stance for which a number of reasons can be adduced.5

First of all, given their lack of firm legal status in Germany – they are not recognised as a ‘corporations of public law’ and thus do not hold a status comparable to Christian churches or Jewish congregations – many Muslim communities have extremely limited financial wiggle room. They are, consequently, at times not in a position to pay the salaries of a fully-trained Imam – and students of Islamic theology are reluctant to accept employment with extremely meagre pay.

Continued reliance on clergymen from abroad

The organisation that could most easily avoid this financial trap is DİTİB, the country’s largest Islamic association with roughly 1,000 Imams. Yet DİTİB is a subsidiary of the Turkish government’s Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) and as such only employs Imams trained in and funded by Turkey.

To be sure, DİTİB spokesman Zekeriya Altuğ has affirmed that the mosques of his organisation will gradually move towards relying on German-trained Imams.6 Altuğ has also stressed DİTİB’s overall willingness to emancipate itself from its Turkish superiors.7

Yet it remains doubtful whether the organisation will be either willing or capable to accomplish such a manoeuvre in the near future, particularly given the recent reassertion of central control from Ankara.

Distrust between theology chairs and associations

Scepticism about the suitability of potential Imams trained at German university extends beyond DİTİB, however. The 300 mosques of the Central Council of Muslims in Germany (ZMD) do fund their Imams through private donations, without relying on a financially strong state backer. Nevertheless, they have not embraced the idea of turning to graduates of Germany’s Islamic theology seminaries.

It seems likely that this reticence is linked to disputes over personnel choices and over the content of the curricula at Islamic theology faculties. On both of these matters, the more liberal-leaning faculties (with backing from universities and public authorities) and the more conservative Islamic associations have often clashed bitterly.

‘Liberals’ vs. ‘conservatives’

Generally, the liberals have had the upper hand, to the chagrin of their opponents. Consequently, Aiman Mazyek, chairman of the ZMD, criticised the tendency to “see university institutions as counter-models to the mosques”.

He claimed that the dichotomisation into “enlightened” university Islam and “backward” practices of mosque communities “does particular harm to the reputation of university institutions. For after all it is the congregations that are supposed to employ the graduated Imams one day.” In other words, the ZMD’s constituent communities continue to be suspicious of the ideological orientation of the university degree holders.8

Managing students’ expectations

At the same time, members of the ‘liberal’ university teaching staff have themselves expressed some dissatisfaction with their students and their outlook on the Islamic theology curriculum.

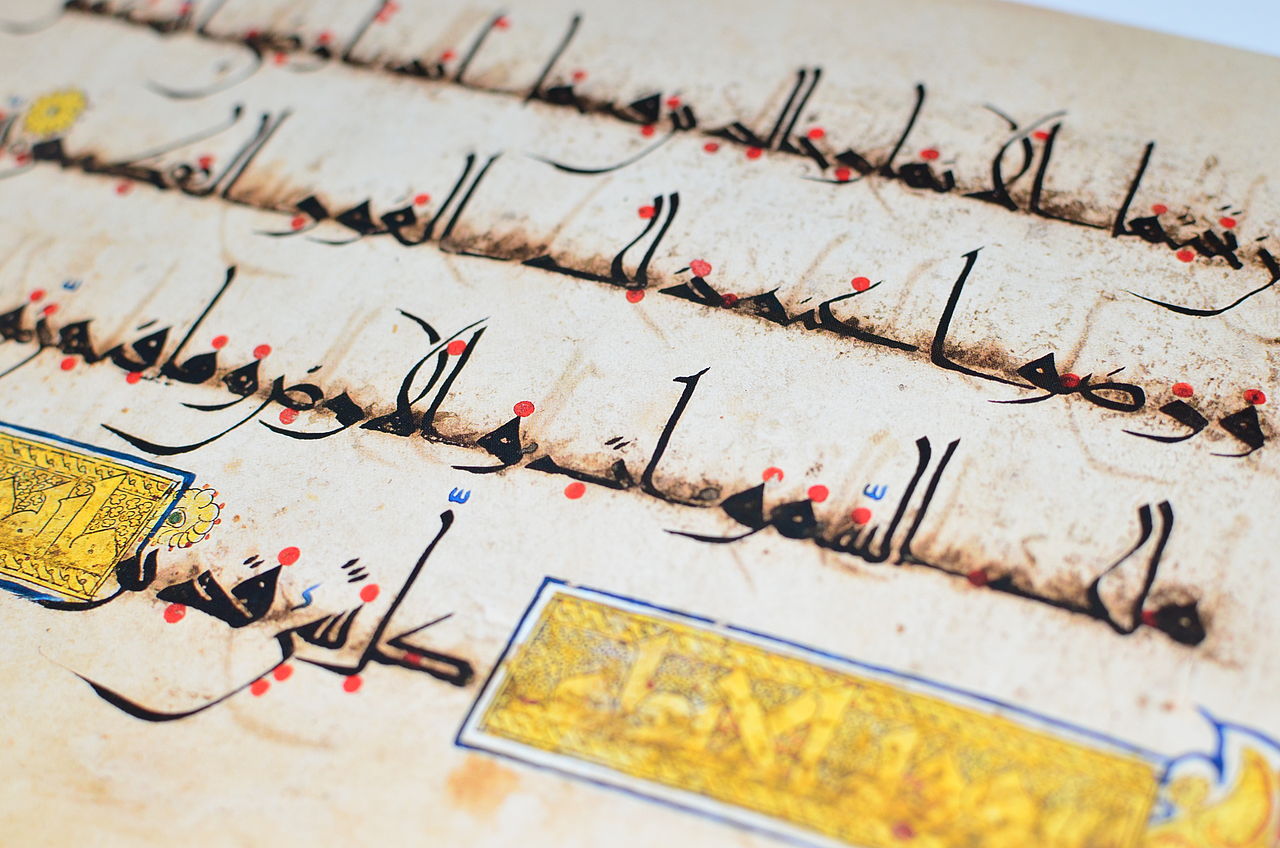

According to Harry Harun Behr, Professor of Religious Education at the University of Frankfurt, many students “seek to deepen their faith, not to work scientifically. When I tell them that the Qur’an is the result of a theological discourse, they don’t want to hear.”9

Professor Mouhanad Khorchide of Münster University concurred: Many students “want to have their faith confirmed”, he asserted, “but university is a place to reflect on faith”. According to him, it would take at least two or three additional generations of students for this point to be accepted across the board.10

Positive results

A little more than five years after the creation of the new faculties, policymakers as well as Islamic scholars and theologians nevertheless continue to see the experiment in positive light.11

Academic observers have stressed that, among other beneficial contributions, the establishment of departments of Islamic theology has helped to bring a more adequate and more intellectually sophisticated Muslim voice to current debates; debates which are all too often controlled by questionable “Islam experts” without any solid theological credentials.12 Indeed, Muslim theologians have not shied away from weighing in on controversial issues.

Islamic theology’s struggle for independence

Thus, there are encouraging signs. They might enable Islamic theology at German universities to transcend its twofold challenge: first, like any new academic discipline, it needs to establish itself and find its own turf – institutionally as well as intellectually. This, by itself, is not an easy feat to accomplish.

In the case of Islamic theology, a second and more particular hurdle presents itself, linked to the inherently contested nature of the study of Islam itself. The most powerful factions seeking to gain definitional authority and dominance over the field are conservative Islamic associations on the one hand and public authorities on the other hand.

While the latter are ostentatiously more liberal than the former, they are nevertheless bent on enforcing their security agenda and on creating a state-backed ‘moderate’ Islam. If Islamic theology wants to come of age in Germany, it must shake off the demands of both sides and strive to cut its own path.

Sources

See Ceylan, Rauf (2009). Prediger des Islam. Imame – Wer sie sind und was sie wirklich wollen. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder. ↩

http://www.zeit.de/2016/07/islamische-theologie-universitaet-fach-studium-bilanz/komplettansicht ↩

http://www.deutschlandfunk.de/wohlfahrtspflege-der-religionsgemeinschaften-muslimische.886.de.html?dram:article_id=346493 ↩

http://www.rp-online.de/panorama/deutschland/imam-ausbildung-in-deutschland-studierende-wollen-nicht-imam-werden-aid-1.6046869 ↩

http://www.rp-online.de/panorama/deutschland/imam-ausbildung-in-deutschland-studierende-wollen-nicht-imam-werden-aid-1.6046869 ↩

http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/f-a-s-exklusiv-ditib-will-unabhaengiger-werden-14386218.html ↩

http://www.rp-online.de/panorama/deutschland/imam-ausbildung-in-deutschland-studierende-wollen-nicht-imam-werden-aid-1.6046869 ↩

http://www.zeit.de/2016/07/islamische-theologie-universitaet-fach-studium-bilanz/komplettansicht ↩

http://www.zeit.de/2016/07/islamische-theologie-universitaet-fach-studium-bilanz/komplettansicht ↩

https://en.qantara.de/content/europe-and-its-muslims-islamic-theology-in-germany-spanning-the-divide?nopaging=1 ↩

Antes, Peter and Rauf Ceylan (2017). “Die Etablierung der Islamischen Theologie: Institutionalisierung einer neuen Disziplin und die Entstehung einer muslimischen scientific community”. In Antes and Ceylan (eds.), Muslime in Deutschland: Historische Bestandsaufnahme, akutelle Entwicklungen und zukünftige Forschungsfragen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. ↩