Germany is, as is well known, home to a large community with Turkish roots, numbering roughly 3 million. Many of them have lived in the country for generations, and roughly half now hold German citizenship – even if the widespread parlance of ‘second-, third-, and fourth-generation immigrants’ stubbornly continues to emphasise their quintessential Otherness.

In recent years, political relations between Germany and Turkey have soured. Domestically, German Turks’ loyalty has been ceaselessly questioned. Stereotypes and racial slurs that many had thought were a thing of bygone eras have been rehabilitated, as right-wing politicians insult German Turks as “camel herders” and “caraway traders” (Turks hardly have camels and their cuisine does not contain caraway.)1

Anti-Turkish hysteria

A new low point was reached when two German football players of Turkish extraction took a photo with Turkish president Erdoğan in the context of a charity event. A media storm ensued during which the players were essentially told that they were undeserving to be German. Subsequently, 80 per cent of respondents to a poll asserted that the two should be expelled from the German national team.

Marco Reus has been replaced by Ilkay Gündogan and fans aren’t happy. Boos and whistles every time the ManCity player is on the ball. #GERKSA pic.twitter.com/UiM84i6loz

— Hecko Flores (@hecko90) June 8, 2018

When he came on during a pre-World Cup friendly against Saudi

Arabia, German fans booed player İlkay Gündoğan at every touch

of the ball for his photo with Turkish President Erdoğan.

It is of course true that under Erdoğan Turkey has embarked on an authoritarian political project, severely restricting central rights and freedoms – not least of the press. The German media is of course not submitted to the dictates of an autocratic ruler. Yet the demands of the German news market have resulted in an Erdoğan-centred coverage of Turkish affairs that sometimes seems almost as tendentious and histrionic as the news emanating from the regime-controlled press on the Bosporus.

As a result, Germany has witnessed a ratcheting of anti-Turkish racism; a racism that often hides behind the self-righteous guise of the defence of democratic freedoms in Turkey.2

German Turks: politically immature and backward

Perhaps most notable has been the complete unwillingness of large parts of the German media and societal establishments to ask the hard question why large numbers of German Turks continue to support President Erdoğan. (In the controversial 2017 constitutional referendum, 63.1 per cent of those German Turks eligible to vote backed the presidential system.)

Most German commentators seem content to explain this support by pointing – in a more or less veiled manner – to German Turks’ supposed political backwardness and immaturity. In its benevolent, liberal-left version, this argument takes the form of the paternalistic assertion that most German Turks are the descendants of poor manual workers from rural Anatolia who don’t know any better.

The perhaps more widespread assumption is that Turks – and their Muslim religion – are simply alien to the values of democracy. In this view, German Turks only have themselves and their cultural recalcitrance to blame for failing to ‘integrate’ into German society. The individual and collective inferiority of ‘the Turk’ is very much taken for granted.

Political disagreements between father and son

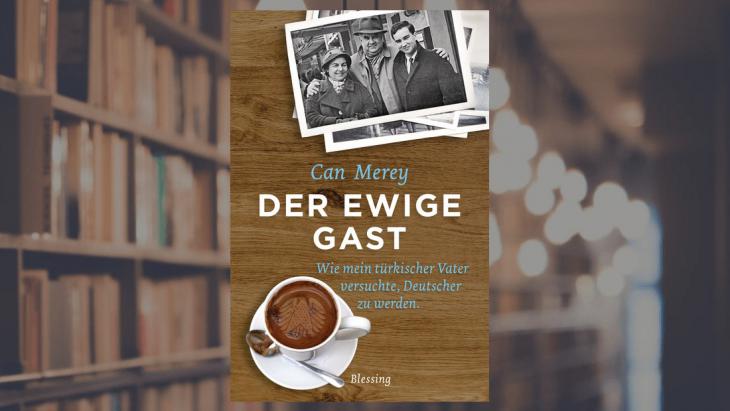

Journalist Can Merey has written an intensely personal book that challenges all these presuppositions. Entitled The Eternal Guest (Der Ewige Gast in German), the book chronicles the struggles of Merey’s father Tosun as he sought for decades to fulfil the role and acquire the standing of a model German citizen. (The book’s subtitle reads: How My Turkish Father Tried to Become German.)

Can Merey, who currently serves as the Istanbul correspondent of Germany’s leading press agency DPA, was compelled to write the book as he noted how, in the aftermath of the 2013 Gezi protests, his father developed into a vigorous defender of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s policies.

As a man of the press, Can Merey was initially left shocked and aghast by his father’s (new) politics. After a vigorous purge of the media landscape, 150 journalists continue to be imprisoned in Turkey today. Merey set out to write the book in order to come to terms with his father’s shift of political opinion. In the process, he wrote the story of what Tosun Merey himself describes as an “unrequited love” for Germany.3

Tosun Merey’s attempt at ‘integration’

For Tosun Merey did in fact try very hard to please his love interest. After coming to Germany in 1958, he studied at Munich’s prestigious Ludwig-Maximilian-University; he acquired German citizenship; he married a German wife from conservative-Catholic Upper Bavaria; he only spoke German to his children; his circle of friends was purely German; he worked in well-regarded jobs; and he took a liking to Bavarian wheat beer and pork roast.4

In a glowing book review, the left-leaning TAZ newspaper refers to a number of the central accusations routinely levelled against German Turks and asks laconically: “Has he [Tosun Merey] spent is life in one of the oft-invoked ‘parallel societies’, acquired no German skills, only watched Turkish television and spent his free time in one of these male-dominated cafés where Germans practically don’t have the right to enter? Has he taken refuge in Islam and has he placed shari’a above the Basic Law?”5

Needless to say, none of this is the case. As Can Merey observes, his father “fulfilled every demand that is still regularly directed at all foreigners coming to Germany today. […] He really tried to become German”. So why does this man now support President Erdoğan and, after sixty years in Germany, has come to consider himself as above all a Turk?6

Everyday racism

Can Merey in fact chronicles the slow and agonising “failure” of his father’s “life project” of making a home in Germany. For over the course of sixty years, Tosun Merey never managed to shake of the feeling of being a “second-class citizen”.

This did not involve in life-altering events, such as open racist violence. Rather, Tosun Merey’s second-class status manifested itself in a never-ending series of everyday humiliations and setbacks: In his company, some colleagues did not want to work together with ‘a Turk’. When Tosun Merey and his family lived in Iran on a temporary assignment from a German company, his children were not admitted to the German kindergarten for racial considerations. Back in Germany, his sons were insulted as ‘Kanacken’, a racial slur levelled at persons of Turkish descent. When they were looking for a place to live, they were told that no apartments would be given to “foreigners”.

The book also describes how Tosun Merey was particularly hurt at the depiction of Turks in Germany’s mainstream media. Throughout the 1970s and the 1980s, respected magazines and newspapers like Der Spiegel or Die Zeit ran headlines such as “The Turks are coming, save yourselves if you can!” or “Close the gates, the Turks are coming!”. (While immigrants and their descendants are ceaselessly encouraged today to consume only German media, this shows that the supposed benefits of ‘integration’ resulting therefrom might unsurprisingly be elusive if newspapers continue to dish out xenophobic hatred.)7

"Was macht Erdogan für Menschen mit türkischen Wurzeln gerade in Deutschland so attraktiv?" @ChristophScheff hat mich für @hrinfo zu meinem Buch "Der ewige Gast" interviewt https://t.co/IfbcrcKaw1

— Can Merey (@CanMerey) May 19, 2018

Journalist Can Merey presents his book ‘The Eternal Guest’.

Never more than ‘just another Turk’

What is particularly interesting about the story of Tosun Merey is of course that he represents everything that the acolytes of a German ‘guiding culture’ are looking for in a role model: well-educated, hard-working, law-abiding, beer-drinking, and pork-eating.

In fact, Tosun Merey’s particular disappointment results from precisely this fact: As the offspring of an Istanbul businessman, he is an educated, avowedly ‘modern’ and secularist member of the middle class. As such, Tosun Merey was deeply hurt at being lumped together with the large numbers of workers who came to Germany as impoverished and more religious migrants from rural Anatolia.8

However, the dynamic of racialisation and exclusion rode roughshod over Tosun Merey’s sense of distinction – some might say his arrogance – and assimilated him to the inchoate masses of the ‘guest workers’ in front of whom Germany’s gates had to be closed.

‘Erdoğan has given me back my pride’

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, first as Prime Minister and then as President, has “given me back my pride”, Tosun Merey asserts. Speaking to Deutschlandfunk radio, he accepts the fact that Erdoğan “rules via an authoritarian system in Turkey”. Yet the 78-year-old also complains that “often something is depicted as false just because Erdoğan said it.”9

Prior to writing the book, his son Can would have found this line of reasoning incomprehensible: How could his father defend an autocrat, and how could the fact that occasionally Erdoğan’s words were misrepresented justify this support?

Yet with the book finished and published, Can Merey acknowledges that the process of writing and reflection has made him “much more understanding of the Turks in Germany.” In particular, he criticises how “many Germans equate Turkey and Erdoğan […]. So I sometimes feel that there is a dislike of Turks that breaks to the fore that is not really directed against Erdoğan at all but against Turkey in general. There is an underlying hostility towards Turks (Türkenfeindlichkeit) in Germany that is hurtful to many German Turks.”10

Germany’s inability to use the R-word

If a leading journalist speaks about deeply ingrained patterns of Türkenfeindlichkeit and of institutional racism, this might seem unremarkable to British or American audiences – not in the sense that there is no racism in Anglo-American societies, but in the sense that the discussion of racial discrimination is a routine part of public discourse.

In the German context, however, matters are different. As scholars have observed, the very notion of racism is often a taboo subject: “The legacy of the Shoah […] has meant that the word ‘Rassismus’ (racism) is equated with ‘Nazism’ by many white Germans. The consequence is that inevitably all discussions on the subject hit a ‘but I am not racist!’ dead end.”11

As a response, many German activists refrain from using the term ‘racism’ in their advocacy work, fearing that if they do their concerns will not be heard. Yet this pragmatic choice also risks silencing them, since they lack the appropriate vocabulary to describe the structures of oppression they face.

Beyond Tosun Merey

To be sure, a single biography such as the one delivered by Can Merey cannot resolve all these issues. Nor can it be fully representative of the experiences of millions of German Turks. However, Tosun Merey’s story, for all its particularities, does not seem exceptional: In a 2016 representative study by the University of Münster, more than half of German Turks asserted that they felt relegated to the status of second-class citizens.12

These survey results highlight obvious issues of discrimination, racism and xenophobia. Yet instead of facing these uncomfortable questions, the main reception of the study focused on something entirely different – namely the “Islamic-fundamentalist attitudes” supposedly widespread among German Turks. The basis for this accusation was that 47 per cent of the study’s respondents had asserted that the commands of their faith were more important to them than German laws.

Not only is this a sentiment that religious believers of any tradition would conceivably support. (Surely Christians cannot seriously place the Basic Law over the commands of the Almighty.) In fact, the very idea that it is problematic if German Turks stress their loyalty to the precepts of their faith fundamentally relies on the notion that one cannot be a believing Muslim and a German citizen at the same time. This is precisely the kind of often implicit and unconscious racism that drove Tosun Merey into Erdoğan’s waiting arms.

Sources

Germany is, as is well known, home to a large community with Turkish roots, numbering roughly 3 million. Many of them have lived in the country for generations and roughly half now hold German citizenship – even if the widespread parlance of ‘second-, third-, and fourth-generation immigrants’ stubbornly continues to emphasise their quintessential Otherness.

In recent years, political relations between Germany and Turkey have soured. Domestically, German Turks’ loyalty has been ceaselessly questioned. Stereotypes and racial slurs that many had thought were a thing of bygone eras have been rehabilitated, as right-wing politicians insult German Turks as “camel herders” and “caraway traders” (Turks don’t hold camels, nor does their cuisine contain caraway.)13

A new low point was reached when two German football players of Turkish extraction took a photo with Turkish president Erdoğan in the context of a charity event. A media storm ensued during which the players were essentially told that they were undeserving to be German. Subsequently, 80 per cent of respondents to a poll asserted that the two should be expelled from the German national team.

It is of course true that under Erdoğan Turkey has embarked on an authoritarian political project, severely restricting central rights and freedoms – not least of the press. The German media is of course not submitted to the dictates of an autocratic ruler. Yet the demands of the German news market have resulted in an Erdoğan-centred coverage of Turkish affairs that sometimes seems almost as tendentious and histrionic as the news emanating from the regime-controlled press on the Bosporus.

As a result, Germany has witnessed a ratcheting of anti-Turkish racism of enormous proportions; a racism that often hides behind the self-righteous guise of the defence of democratic freedoms in Turkey

Perhaps most notable has been the complete unwillingness of large parts of the German media and societal establishment to ask the hard question why large numbers of German Turks continue to support President Erdoğan. (In the controversial 2017 constitutional referendum, 63.1 per cent of those German Turks eligible to vote supported Erdoğan’s presidential system.)

However, most German commentators seem content to explain thus support by pointing – in a more or less veiled manner – to German Turks’ supposed political backwardness and immaturity. In its benevolent, liberal-left version, this argument takes the form of the paternalistic assertion that most German Turks are the descendants of poor manual workers from rural Anatolia who don’t know any better.

The perhaps more widespread assumption is that Turks – and their Muslim religion – are simply alien to the values of democracy. In this view, German Turks only have themselves and their cultural recalcitrance to blame for failing to ‘integrate’ into German society, or so the argument goes. The individual and collective inferiority of ‘the Turk’ is very much taken for granted.

Journalist Can Merey has written an intensely personal book that challenges all these presuppositions. Titled The Eternal Guest (Der Ewige Gast in German), the book chronicles the struggles of Merey’s father Tosun as he sought for decades to fulfil the role of a model German citizen. (The book’s subtitle reads: How My Turkish Father Tried to Become German.)

Can Merey, who currently serves as the Istanbul correspondent of Germany’s leading press agency DPA, was compelled to write the book as he noted how, in the aftermath of the 2013 Gezi protests, his father developed into a vigorous defender of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s policies.

As a man of the press, Can Merey was initially left shocked and aghast by his father’s (new) politics: after a vigorous purge of the press landscape, 150 journalists continue to be imprisoned in Turkey today. Thus, Merey set out to write the book in order to come to terms with his father’s shift of political opinion. In the process, he wrote the story of what Tosun Merey himself describes as an “unrequited love” for Germany.14

For Tosun Merey did in fact try very hard to please his love interest. After coming to Germany in 1958, he studied at Munich’s prestigious Ludwig-Maximilian-University; he acquired German citizenship; he married a German wife from conservative-Catholic Upper Bavaria; he only spoke German to his children; his circle of friends was purely German; he worked in well-regarded jobs; and he took a liking to Bavarian wheat beer and pork roast.15

In a glowing book review, the left-leaning TAZ newspaper refers to a number of the central accusations routinely levelled against German Turks and asks laconically: “Has he [Tosun Merey] spent is life in one of the oft-invoked ‘parallel societies’, acquired no German skills, only watched Turkish television and spent his free time in one of these male-dominated cafés where Germans practically don’t have the right to enter? Has he taken refuge in Islam and has he placed shari’a above the Basic Law?”16

Needless to say, none of this is the case. As Can Merey observes, his father “fulfilled every demand that is still regularly directed at all foreigners coming to Germany today. […] He really tried to become German”. So why does this man now support President Erdoğan and, after sixty years in Germany, has come to consider himself as above all a Turk?17

Can Merey in fact chronicles the slow and agonising “failure” of his father’s “life project” of making a home in Germany. For over the course of sixty years, Tosun Merey never managed to shake of the feeling of being a “second-class citizen”.

This did not involve in life-altering events, such as open racist violence. Rather, Tosun Merey’s second-class status manifested itself in a never-ending series of everyday humiliations and setbacks: In his company, some colleagues did not want to work together with ‘a Turk’. When Tosun Merey and his family lived in Iran on a temporary assignment from a German company, his children were not admitted to the German kindergarten for racial considerations. Back in Germany, his sons were insulted as ‘Kanacken’, a racial slur levelled at persons of Turkish descent. When they were looking for an apartment, they were told that no apartments would be given to “foreigners”.

The book also describes how Tosun Merey was particularly hurt at the depiction of Turks in Germany’s mainstream media. Throughout the 1970s and the 1980s, magazines and newspapers such as Der Spiegel and Die Zeit ran headlines such as “The Turks are coming, save yourself if you can!” or “Close the gates, the Turks are coming!”. (While immigrants are their descendants are today ceaselessly encouraged to consume only German media, this shows that the supposed benefits of ‘integration’ resulting therefrom might unsurprisingly be elusive if newspapers continue to dish out xenophobic hatred.)18

What is particularly interesting about the story of Tosun Merey is of course that he represents everything that the acolytes of a German ‘guiding culture’ are looking for in a role model: well-educated, hard-working, law-abiding, beer-drinking, and pork-eating.

In fact, Tosun Merey’s particular disappointment results from precisely this fact: As the offspring of an Istanbul businessman, he is an educated, avowedly ‘modern’ and secularist member of the middle class. As such, Tosun Merey was deeply hurt at being lumped together with the large numbers of workers who came to Germany as impoverished and more religious migrants from rural Anatolia.19

However, the dynamic of racialisation and exclusion rode roughshod about Tosun Merey’s sense of distinction (some might say his arrogance) and assimilated him to the inchoate masses of the ‘guest workers’ in front of whom Germany’s gates had to be closed.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, first as Prime Minister and then as President, has “given me back my pride”, Tosun Merey asserts. Speaking to Deutschlandfunk radio, he accepts the fact that Erdoğan “rules via an authoritarian system in Turkey”. Yet the 78-year-old also complains that “often something is depicted as false just because Erdoğan said it.”20

Prior to writing the book, his son Can would have found this line of reasoning incomprehensible: How could his father defend an autocrat, and how could the fact that occasionally Erdoğan’s words were misrepresented justify this support?

Yet with the book finished and published, Can Merey acknowledges that the process of writing and reflection has made him “much more understanding of the Turks in Germany.” In particular, he criticises how “many Germans equate Turkey and Erdoğan […]. So I sometimes feel that there is a dislike of Turks that breaks to the fore that is not really directed against Erdoğan but against Turkey in general. There is an underlying hostility towards Turks (Türkenfeindlichkeit) in Germany that is hurtful to many German Turks.”21

If a leading journalist speaks about deeply ingrained patterns of Türkenfeindlichkeit and of institutional racism, this might seem unremarkable to British or American audiences – not in the sense that there is no racism in Anglo-American societies, but in the sense that the discussion of racial discrimination is a routine part of public discourse.

In the German context, however, matters are different, where the very notion of racism is a taboo subject: “The legacy of the Shoah […] has meant that the word ‘Rassismus’ (racism) is equated with ‘Nazism’ by many white Germans. The consequence is that inevitably all discussions on the subject hit a ‘but I am not racist!’ dead end.”22

As a response, many German activists refrain from using the term ‘racism’ in their advocacy work, fearing that if they do their concerns will not be heard. Yet this pragmatic choice also risks silencing them, since they lack the appropriate vocabulary to describe the structures of oppression they face.

To be sure, a single biography such as the one delivered by Can Merey cannot resolve all these issues. Nor can it be fully representative of the experiences of millions of German Turks. However, Tosun Merey’s story, for all its particularities, does not seem exceptional: In a 2016 representative study by the University of Münster, more than half of German Turks asserted that they felt relegated to the status of second-class citizens.23

These survey results highlight obvious issues of discrimination, racism and xenophobia. Yet instead of facing these uncomfortable questions, the main reception of the study focused on something entirely different. Reporting on the study mainly discussed the “Islamic-fundamentalist attitudes” supposedly widespread among German Turks, given the fact that 47 per cent of respondents had asserted that the commands of their faith were more important to them than German laws.

Not only is this a sentiment that religious believers of any tradition would support. (Surely Catholic Christians cannot seriously place the Basic Law over the commands of the Almighty.) In fact, the very idea that it is problematic if German Turks stress their loyalty to the precepts of their faith fundamentally relies on the notion that one cannot be a believing Muslim and a German citizen at the same time. This is precisely the kind of often implicit and unconscious racism that drove Tosun Merey into the arms of Erdoğan.

http://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/afd-politiker-poggenburg-ermittlungen-wegen-volksverhetzung-eingestellt-1.4002870 ↩

http://www.spiegel.de/sport/fussball/pfiffe-gegen-ilkay-guendogan-es-geht-nicht-um-politik-kommentar-a-1212076.html ↩

https://www.hr-inforadio.de/programm/das-interview/das-interview-mit-can-merey-autor-und-journalist,can-merey-100.html ↩

https://www.hr-inforadio.de/programm/das-interview/das-interview-mit-can-merey-autor-und-journalist,can-merey-100.html ↩

https://www.hr-inforadio.de/programm/das-interview/das-interview-mit-can-merey-autor-und-journalist,can-merey-100.html ↩

https://www.hr-inforadio.de/programm/das-interview/das-interview-mit-can-merey-autor-und-journalist,can-merey-100.html ↩

https://www.hr-inforadio.de/programm/das-interview/das-interview-mit-can-merey-autor-und-journalist,can-merey-100.html ↩

http://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/can-merey-der-ewige-gast-von-einem-der-auszog-um-sich-in.2165.de.html?dram:article_id=414935 ↩

http://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/can-merey-der-ewige-gast-von-einem-der-auszog-um-sich-in.2165.de.html?dram:article_id=414935 ↩

Sharon Dodua Otoo “‘The Speaker is using the N-Word’: A Transnational Comparison (Germany-Great Britain) of Resistance to Racism in Everyday Language. In Karim Fereidooni and Meral El (eds.), Rassismuskritik und Widerstandsformen, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2017, p. 293. ↩

https://www.uni-muenster.de/Religion-und-Politik/aktuelles/2016/jun/PM_Integration_und_Religion_aus_Sicht_Tuerkeistaemmiger.html ↩

http://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/afd-politiker-poggenburg-ermittlungen-wegen-volksverhetzung-eingestellt-1.4002870 ↩

https://www.hr-inforadio.de/programm/das-interview/das-interview-mit-can-merey-autor-und-journalist,can-merey-100.html ↩

https://www.hr-inforadio.de/programm/das-interview/das-interview-mit-can-merey-autor-und-journalist,can-merey-100.html ↩

https://www.hr-inforadio.de/programm/das-interview/das-interview-mit-can-merey-autor-und-journalist,can-merey-100.html ↩

https://www.hr-inforadio.de/programm/das-interview/das-interview-mit-can-merey-autor-und-journalist,can-merey-100.html ↩

https://www.hr-inforadio.de/programm/das-interview/das-interview-mit-can-merey-autor-und-journalist,can-merey-100.html ↩

http://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/can-merey-der-ewige-gast-von-einem-der-auszog-um-sich-in.2165.de.html?dram:article_id=414935 ↩

http://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/can-merey-der-ewige-gast-von-einem-der-auszog-um-sich-in.2165.de.html?dram:article_id=414935 ↩

Sharon Dodua Otoo “‘The Speaker is using the N-Word’: A Transnational Comparison (Germany-Great Britain) of Resistance to Racism in Everyday Language. In Karim Fereidooni and Meral El (eds.), Rassismuskritik und Widerstandsformen, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2017, p. 293. ↩

https://www.uni-muenster.de/Religion-und-Politik/aktuelles/2016/jun/PM_Integration_und_Religion_aus_Sicht_Tuerkeistaemmiger.html ↩