written by Simon Sorgenfrei

Demographics

Even though Sweden, or what today is Sweden, has a long history of commercial and political contacts with countries dominated by Muslim culture – dating back to the Viking era1 and peaking with Swedish-Ottoman contacts in the seventeenth and especially eighteenth centuries2– Muslim presence in Sweden is a fairly recent phenomenon.

At the last census to include information on religious affiliation in 1930, 15 persons identified themselves as Muslims.3 This first small group of Muslims in Sweden were primarily of Baltic Tartar origin.4 Today the number of Muslims in Sweden is estimated to be approximately 400.000.5 Out of these, the Swedish Commission for state Grants to Religious Communities (SST) estimate 110.000 to be practising Muslims.6 In their big survey Islam and Muslims in Sweden – A Contextual Study, Larsson and Sander (2007) believes this estimation to be to low, and the result of SST’s “conservative and exclusive” definition, “only counting individuals who belong to congregations that are ‘recognized’ by itself.”7 According to their estimation the number of practising Muslims is closer to 150.000 individuals.8

Sander has acknowledged the problem of defining the term “Muslim” in Sweden.9 He presents four categories: Ethnic-, Cultural-, Religious-, and Political Muslims. An “ethnic Muslim” defines anyone:

“who has been born in an environment dominated by a Muslim tradition […] and carries a name that is attached to that tradition; also included in this category are those who identify with, or consider themselves to belong to, one or the other of these environments. This particular definition is independent of cultural competence, religious belief, active participation in Islam as a religious system, and/or individual attitudes regarding Islam and its various representatives.10”

A “cultural Muslim” is anyone who:

“has been socialized into the Muslim cultural tradition […] such that it has become an integral part of his/her attitudes and beliefs, and who has Muslim cultural competence as well [and] for whom the Islamic cognitive universe is the phenomenon through which they constitute and experience themselves and their life-world.”11

Someone can be considered a religious Muslim “if (s)he professes allegiance to a specific set of beliefs, participates in certain religious services and practices, and considers personal piety and other such religious elements to be essential to her/his personal lifestyle.”12 And as a political Muslim, finally, he considers someone who “views Islam primarily as a socio-political phenomenon, and has specific ideas about the place, role and function of religion in society [and] tend to view Islam as a total way of life, not only for the individual, but also for society at large.”13 These categories can, of course, be overlapping.

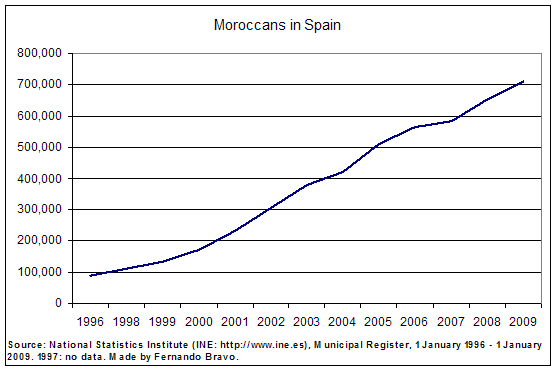

Today Sweden has one of the most heterogeneous Muslims populations in Western Europe, coming from more than 40 different countries of origin. The first group of Muslims of any number to arrive in Sweden were Turks coming as guest workers, probably with no ambitions to stay in Sweden, in the late 1960s. Many of them stayed, however, and as their families began to arrive in the 1970s and 1980s the requirement for institutions helping to uphold and preserve cultural and religious needs and values began to be felt. (More on the institutionalization of Islam in Sweden under the heading Organizations).

The 1980s also saw a growing Muslim population of refugees, and since then the Muslims of Turkish background are no longer in majority. The most influential groups come from Iraq, Iran, Somalia, the Balkans and Pakistan.14

Most Swedish Muslims live in and around the three largest cities – Stockholm, Göteborg and Malmö – and the great majority lives in suburbs such as Rinkeby, Tensta or Skärholmen in Stockholm, Biskopsgården, Hammarkullen and Hjällbo in Göteborg, and Rosengård in Malmö.

Labor Market

Even though there has been more or less consensus within Swedish politics that employment will promote integration, studies show that access to the labor market have decreased in the general for immigrants (not only Muslims) since the 1970s.15 According to Bevelander et al. (1997, Ch. 2) the failure of Sweden to give immigrant access to the labor market is so considerable that it (hand in hand with Norway and Denmark) resides at the bottom of the statistics in comparison to the rest of the industrialized world.

Even if they are fortunate enough to get a job, “most Muslim immigrants are forced to work in positions far below their level of education, training and skill. Employed foreign born are, consequently, to be fund [sic] primarily in branches with high amount of unqualified jobs, part of the industry sector, the hotel- and restaurant sector together with the private service sector.”16 Larsson and Sander conclude that “many labor market reserachers have drawn the conclusion that the mere happenstance of being an immigrant – and particularly a black or Muslim immigrant – is, in and of itself, a sufficient disqualification in terms of securing gainful employment in Sweden…”17 Many [Muslim] immigrants have chosen, or been forced into, self employment as a response to the poor situation on the Swedish labor market.

Schooling was made obligatory for all children in Sweden in 1842. The most important subject back then was religious instruction under influence of the Lutheran State Church. This was the case until 1919 – the starting point of the secularization of the Swedish school system – when religious instruction were reduced by fifty percent. In 1962, a school reform required the subject of Christianity to maintain a “neutral” profile with respect to questions of faith; and in 1969, the subject’s name was changed from Christianity to Religious Education (religionskunskap), indicating the transition from a confessional to a non-confessional form of religious education that prioritised teaching about religion—including different religions, rather than teaching into a religion (e.g Christianity).18

“The school has the important task of imparting, instilling and forming in pupils those values on which our society is based. The inviolability of human life, individual freedom and integrity, the equal value of all people, equality between women and men and solidarity with the weak and vulnerable are all values that the school shall represent and impart. In accordance with the ethics borne by Christian tradition and Western humanism, this is achieved by fostering in the individual a sense of justice, generosity of spirit, tolerance and responsibility. Education in the school shall be non-denominational.19”

In accordance with Sweden’s Educational Act, these guidelines are to be followed by all schools – whether non-confessional or confessional.

Housing

As a result of the financial situation following immigrant’s low status in the Swedish labor market most immigrants of African and Asian origin can be found in Sweden’s poorer neighborhoods – so called “disadvantaged areas”.20 The commission on Housing Policy (Bostadspolitiska utredningen) define these as follows:

State and Church

January 1, 2000 saw what has been called a formal separation between the Church of Sweden and the State of Sweden. Even so the Church of Sweden is still more priviledged than other religious organizations and did, for instance, get to keep its properties and real estate – much of which is considered Swedish cultural heritage.

Muslims in the Legislature

According to Larsson and Sander (2007) immigrant representation in Swedish politics is poor.21 There are a few noticeable (ethnic-, cultural-, and religious-) Muslims active in Swedish politics. For instance Nalin Pekgul, of Turkish-Kurdish origin, who held representation in the Parliament of Sweden between 1994-2002. Since 2003 she’s the chairman of the The National Federation of Social Democratic Women in Sweden. Another politician of Turkish origin is Mehmet Kaplan who is a member of Parliament of the Swedish Environmental Party, member of the Swedish Committee of Justice, deputy of the Swedish Committee of Foreign Affairs, and deputy of the EU-Committee. Prior to his political commissions Kaplan was secretary (1996-2000) and later chairman (2000-2002) of Sweden’s Young Muslims (SUM) and spokesperson (2005-2006) of the Swedish Muslim Council (SMR).

In Anne Sofie Roald’s Muslimer i nya samhällen (Muslim’s in New Societies) (2009) seven persons in the Parliament with names indicating Muslim background were approached with a questionnaire about their religious affiliation, out of these two affirmed a Muslim identity. According to Roald a great majority (80 percent in 2002) of Sweden’s Muslims vote for left wing parties. But even so, she concludes, most Muslims in Sweden seem to have family- and moral values agreeing more with the politics of the right wing, or conservative parties.22

February 2010 Mosa Sayed defended his much noticed dissertation Islam och arvsrätt i det mångkulturella Sverige. En internationellt privaträttslig och jämförande studie (Islam and Inheritance Law in Multicultural Sweden. A Study in Private International and Comparative law.) He himself summarizes the main concernes of his thesis as follows:

“Immigration has meant that to a large extent Sweden’s population at present is heterogeneous as regards culture and religion. In this doctoral thesis the choice of law rules of Swedish private international law relating to inheritance are elucidated in the context of an intestate succession characterised by Islam, to be precise the Egyptian law of inheritance.

The Egyptian rules are used as an example of a typical Islamic inheritance system. According to the Act (1937:81) on International Legal Relations Concerning Estate, the choice of law rule relating to inheritance is based on the principle of nationality.

This principle means that suitable rules follow the law of the country where the deceased was a citizen at the time of death. Many people in Sweden are citizens of countries with an Islamic inheritance legal order. The Swedish international inheritance rules imply that in these cases the estate will be devolved in accordance with the rules in the country of citizenship, i.e. the Islamic regime.

In this study the Swedish conflict rules are analysed in context of a multicultural Sweden.

What is the function of succession rules based on religion in a non-Muslim society, where a significant proportion of the population identifies themselves with the Islamic law due to their religious views and affiliation?

In what way can a multicultural perspective contribute to the interpretation and application of the international inheritance law regulations in Sweden?”23

Muslim Organizations

Sweden’s first national Muslim federation – Förenade Islamiska Församlingar i Sverige (FIFS) – was founded in 1973 and in 1976 an Ahmadiyya congregation in Göteborg opened the country’s first purpose built mosque. Due to a split in FIFS a second national federation was formed in 1982 called Svenska Muslimska Förbundet (SMuF), and two years later a new group broke out of FIFS and formed Islamiska Centerunionen (ICUS). In 1988 these three federations claimed a total of 38 local congregations and 60.000 registered members. All three have joined SST under the name of Islamiska Samarbetsrådet (IS).

In 1986, FIFS and SMuF created Stiftelsen Islamiska Informationsbyrån (two years later to be renamed Islamiska Informationsföreningen, IIF), aiming at informing Swedish Muslims and non-Muslims alike through informational publications, lectures and such. In 2000 a handful of prominent representatives of Sweden’s Muslim communities founded Svenska Islamiska Akademin with the intention to promote Islamic education and research in Sweden, and working towards an Islamic University that, among other things, would be responsible for the training of imams. FIFS and SMuF also cooperate in Sveriges Muslimska Råd (SMR) created in 1990 to centralize power and act as spokespersons for Sweden’s Muslims in contacts with authorities and to the public at large. That same year the still very active youth organization Sveriges Muslimska Ungdomsförbund (SMuF), later to be renamed to Sveriges Unga Muslimer (SUM) was founded. Other important organizations is the umbrella organization Islamiska Rådet i Sverige (IRIS), Islamiska Kvinnoförbundet i Sverige (IKF) focusing on issues regarding women’s situation, and Sveriges Imamråd (SIR).

Both SMR and IRIS are heavily dominated by Sunni Muslims, but since the 1990 Sweden have seen an increasing amount of denominational and ethnic organizations, such as the Shi’ite Islamiska Shiasamfunden i Sverige (ISS) founded in 1992, or Bosnien-Hercegovinas Islamiska Riksförbund created in 1995.24

January 2011 a Swedish Fatwa Counsel was established by some 10 Imams in Malmö. The ambition of the counsel is to offer guidance to Muslims living in Sweden, making it easier to practice Islam in harmony with Swedish law and culture.

In addition to these organizations there are also Sufi Tariqas and other Muslim congregations not necessarily affiliated with SST.

Islamic Education

Denominational schools in Sweden:

| Christian | Muslim | Jewish | |

| Compulsory schools | 54 | 9 | 3 |

| Upper secondary schools | 6 | 0 | 0 |

In her 2009 thesis Theaching Islam: Islamic Religious Education at Three Muslim Schools in Sweden Jenny Berglund found that:

“it is inaccurate to speak about IRE in homogeneous terms since the content varies distinctively between different schools. In addition, it has been found that the educational questions considered by the involved teachers are similar to those considered by many other types of teachers. Although classroom observations and teacher interviews showed that the general content of all three IRE classrooms included the teaching of the Quran, Islamic history through religious narratives and song, specific content variations were evident. Differences concerned approaches to the teaching of the Quran, ways of using religious narratives and genre of songs. Therefore pupils in each school received somewhat different answers to local and global questions that were raised in the classrooms, indicating somewhat different interpretations of Islam. These differences suggest that the depiction of IRE as a transmission of Islam to the younger generation is not accurate since it leads to the impression that religions are insulated entities that are capable of being passed from one generation to the next without any change taking place. Instead this study shows that the teachers translate the content of IRE according to their perception of what is vital for their pupils to know and suitable for them to comprehend since they constantly choose content and negotiate its meaning.”25

In 2010 Sweden’s first Muslim folk high school – Kista folkhögskola – opened. In 2011 they are investigating the possibility to offer some sort of an Imam education at the school.

Security, Immigration and Anti Terrorism Issues

December 18, 2001 two men of Egyptian origin – Ahmed Agiza and Muhammad al-Zery were deported from Sweden to Egypt on request from the CIA.

Mehdi Ghezali, a young Swedish man of Algerian background, was imprisoned at Guantanamo between January 2002 and July 2004. He was captured in Afghanistan December 2001 and taken to Guantanamo. In September 2009 ha was arrested again, in Pakistan, suspected of dealings with al-Qaida or other terrorist activity in Pakistan. He was released one month later and flown back to Sweden.

Oussama Kassir, a Swede of Lebanese origin, was found guilty on eleven charged brought against him in a terrorist trial by an American federal government in May 2009. Ousamma Kassir was convicted to lifelong imprisonment.

September 25, 2009 the daily newspaper Sydsvenska dagbladet knew to tell at least nine Swedish citizens were jailed around the world, suspected or convicted of crimes related to terrorism.26

Since 2009 there have been many reports about representatives from Somali Islamist network al-Shabaab recruiting in Sweden. According to Swedish Secret Police (SÄPO) ten to twenty Swedish-Somalis have been recruited and about ten persons have gone to Mogadishu to partake in battle.

January 2010 The Swedish government asked the Swedish Secret Police (SÄPO) for a report on radical Islamism in Sweden. “There are indications coming from SÄPO”, said Minister of Integration Nyamko Sabuni, “that violent, radical Islamists are recruiting in Sweden. Even if this is not a big problem, it can have grave consequences for some individuals.” The report was published December 15 2010. In the report “violence inclined Islamist extremism” is defined as “activities threatening security which are Islamistically motivated, and which aims at changing the society in a non-democratic direction by the use of violence or threat of violence.” Radicalization, further, is defined as: “the process leading to a person, or a group, supporting or exercising, ideologically motivated violence to support a case.”

The report was the result of a systematic adaptation and analysis of existing material gathered by Säpo, and focused on 2009. But they also made use of other publically available sources, such as other authority reports and research articles.

According to the report there are approximately 200 individuals engaged in violence inclined Islamist extremism in Sweden – even though this activity mainly pursue to support or aid terrorism in other countries, such as Somalia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and North Africa. The only somewhat common denominator for radicalization amongst these individuals seems to be that the majority consists of men in between 15-30 years of age. Out of these 200 individuals SÄPO estimates 80 percent to have friendly bonds or other connections to each other. Not surprisingly Internet seems to be the common ground for these individuals and groups.

SÄPO states that “the threat from violence inclined Islamist extremism in Sweden is currently not a threat against fundamental societal structures or the Swedish form of government.” The greatest potential threat towards Sweden, SÄPO concludes, is the long term effects of individuals travelling abroad to affiliate with violence inclined Islamist organizations.

The general conclusions of the report are that violence inclined Islamist extremism and radicalization is a reality in Sweden and must be seen as a potential threat. Presently, however, this is to be considered a limited phenomenon which is to be met with general crime preventive measures, already conducted in Sweden. On their homepage Säpo sums the report up as follows:

Violence-promoting Islamist extremism and radicalisation do exist in Sweden and should not be underestimated as potential threats. However, the currently limited occurrences of these phenomena should be countered mainly by an increased focus on preventive measures. These are the main conclusions of the report on violence-promoting Islamist extremism in Sweden presented to Government today.

In February 2010, the Security Service was commissioned by the Government to put together an official report on violence-promoting Islamist extremism. The report contains a description of violence-promoting Islamist extremism in Sweden, discernible radicalization processes and tools and strategies for use in countering radicalization. The overall purpose of the report is to facilitate a more balanced and informed debate on these issues.

Focus on other countries:

According to the report, there are a number of networks based on a violence-promoting Islamist extremist ideology that are currently active in Sweden. Most of these networks focus on action and propaganda against foreign troops in Muslim countries and against governments they see as corrupt and not representing what the networks consider to be the only true interpretation of Islam. Individual who are active in these networks engage in activities aiming to support and facilitate terrorist offenses mainly in other countries.

Relatively limited number of people.

The report also shows that the threat from violence-promoting Islamist extremism in Sweden is currently not a threat to the fundamental structures of society, Sweden´s democratic system or Central Government. This form of extremism may however constitute a threat to both individuals and groups.

Only a relatively limited number of people are involved in violence-promoting Islamist extremism, and the group of active members on whose actions the descriptions in this report are based consists of just under 200 individuals. There is nothing to indicate that the number of people radicalized in Sweden is growing.

The importance of preventive measures:

Violence-promoting Islamist extremism and radicalization should be countered mainly by an increasing focus on preventive measures. Given the substantial similarities in terms of how and why people radicalize, regardless of ideological affiliation, it should be possible to better coordinate preventive efforts and countermeasures targeting various extremist groups.

Experiences and knowledge gained from crime prevention initiatives in general should also play a more prominent role. Preventive work should be engaged in by actors on all levels of society — nationally, regionally as well as locally.

Just days before the publication of the SÄPO report, on the afternoon of December 11, 2010, a suicide bomber blew himself up in downtown Stockholm. The fatal blast occurred 10 minutes after a car exploded and injured two persons on a nearby street. The bombing was defined as a terror crime by Swedish Secret Police (SÄPO).

The Suicide bomber was later identified as Taimour Abdulwahab, a 29-year old Swede of Iraqi origin who was raised in the little town of Tranås in the south of Sweden. Abdulwahab was not in the SÄPO report published days before. One reason for this could be he was living in Luton, England since 2001, where he had studied to become a physical therapist. Some reports suggests he became radicalized through contacts with Hizb ut-Tahrir representatives in a local mosque there. Not long before the suicide bombing in Stockholm he spent some time in the Middle East – possibly Jordan – where he, according to a letter he sent out before the suicide attack – was engaged in Jihad.

He had been in Sweden for about four weeks before the bombing. The first explosion, sending two people to the hospital was set of in a car, filled with canisters of liquefied petroleum gas and fireworks. Minutes later came the other explosion on a side street, parallel to one of the main shopping streets in Stockholm. It seems one of the bombs he had strapped to his body went off prematurely, before he was able to reach his destination (which is unknown), killing just Abdulwahab himself without setting the other bombs off or injuring anyone else.

Roughly ten minutes before the explosions, Abdulwahab is to have sent an e-mail to the Swedish news agency TT and the Security Service in which he referred to the presence of Swedish troops in Afghanistan and the Swedish artist Lars Vilks’ drawing of Muhammad as a roundabout dog. The letter furthermore said: “Now will your children, daughters and sisters die the same way our brothers and sisters die. Our actions will speak for themselves. As long as you don’t end your war against Islam and degradation against the prophet and your foolish support for the pig Vilks.” The message ended with a call to “all Muhajedin in Europe and Sweden. Now is the time to strike, wait no longer. Go forward with whatever you have, even if it is a knife, and I know you have more than a knife. Fear no one, don’t fear prison, and don’t fear death.”

December 29, 2010 four men were arrested in Denmark suspected of planning an attack on the newspaper JyllandsPosten in Copenhagen. Three of these came from Sweden. Later a fifth man connected to the plot against the Danish newspaper, which published the Muhammad cartoons five years back, was arrested in Stockholm. The arrest was preceded by intelligence work by as well the Swedish (SÄPO) and the Danish (PET) Secret Police. According to Jacob Scharf at PET, Several of the suspects could be described “as militant Islamists with connections to international terror networks.”

The arrested men where a 37-year-old Swede of Tunisian background, a 44-year-old Tunisian, a 29-year-old Swede born in Lebanon, a 30-year-old Swede and a 26-year-old Iraqi asylum seeker. “We learned that people in Sweden were planning a terror crime in Denmark. We’ve known about it for several months. These people are known to the police in Sweden. We contacted our Danish colleagues. We’ve had people under intense surveillance,” SÄPO head Anders Danielsson said later.

One of the men arrested in Denmark, a 29-year-old Swede of Lebanese decent, have been arrested two times earlier. In 2007 he was arrested in Somalia together with several other Swedes, including his then 17-year-old fiancée, on suspicions of having fought on the side of Islamic forces in the ongoing battle in Somalia. He was also arrested once in Pakistan two years later. Also detained were, again, his fiancé and the couple’s toddler son, and Mehdi Ghezali. Ghezali is a former inmate of the US-operated Guantánamo Bay prison, who was released in 2004.

Also the man arrested in Stockholm in connection to the plot against JyllandsPosten in Copenhagen has a previous record. He was arrested in Pakistan last year and spent 10 days in a Pakistani prison for having entered the country illegally. According to Säpo, the man was involved in the planning of the Copenhagen attack, but decided to remain in Stockholm for reasons as yet unknown. 28

Bias and Discrimination

As showed above Muslims are being discriminated on the Swedish labor market, and as discussed under the heading “Media and Public Perception of Islam” below there are tangible evidence of discrimination against Muslims in Sweden. There are, writes Susanne Olsson (2009) a structural discrimination aganinst Muslims consisting in a cultural racism depicting Muslims as “the Other” in Swedish society:

Studies show that islamophobia has been increasing in Sweden since 2001, and a Committee against Islamophobia (KOmmitén mot islamofobi) was created in 2005. The Swedish Islamic Literature and Media Watch (Svensk Islamisk Litteratur och Mediebevakning (SILOM)), is a Muslim network that has been formed in to work against stereotyped and negative images of Islam and Muslims in the media and thus promote integration.29

Islamic Practice

There are about 250 Muslim national organizations in Sweden, usually occupying so called “basement mosques”.30 Out of these six are purpose built mosques, four of which are Sunni (in Malmö, Stockholm and Uppsala), one Shi’ia (Trollhättan), and one Ahmadiyya (Göteborg).31

May 2008 the Swedish Government appointed a commission to investigate the need and possibility for a Swedish education of Imams. The commissions report was published in June 2009 and promoted two proposals: 1, to do nothing or, 2, to do more of what is already being done.32

There are few studies of lay Muslims religious and spiritual everyday life in Sweden, but in 2007 Pia Karlsson Minganti successfully defended her thesis, titled “Muslima. Islamisk väckelse och unga muslimska kvinnors förhandlingar om genus i det samtida Sverige”. Miganti is focusing on young Muslim women’s engagement in an Islamic revival in Sweden, showing how they seek gender empowerment through the Qur’an.

Some Muslim traditions and practices are becoming more visible in Swedish everyday life. One example, as discussed in Jenny Berglund and Simon Sorgenfrei’s Ramadan – en svensk tradition (Ramadan – a Swedish Tradition) published in 2009, is the month of fasting during Ramadan and the following celebration of Id al-fitr or Bayram which today is being more recognized as a religious tradition amongst others in Sweden. Super markets and grocery stores has become more attentive to Muslims as customers – 2008 Swedish Muslims are estimated to have been shopping for 1.000.000.000 skr – and prayers and celebrations connected to Id al-fitr are usually being broadcasted in Swedish television. (Berglund and Sorgenfrei 2009). In 2010 Jonas Otterbeck – Assistant Professor of Islamic Studies at the University of Lund – published Samtidsislam – unga muslimer i Malmö och Köpenhamn (Contemporary Islam – Young Muslims in Malmö and Köpenhamn) in which he portrays nine young Muslim’s thoughts on religion, belief and identity. Otterbeck’s informants are all 17 or 18 years of age and of Arabic, Persian or Pakistani ethnic origin.

Otterbeck states he has two political objectives with his book. He wants to present contrasting images to the dominant negative stereotype of Islam and Muslims, and he wants to show how these young Muslims own the right to define their religiosity and how it is to be expressed (or not, one could add). It shows these nine youngsters have got different, but overlapping, relations to their religion and that their religiosity to a far degree complies with the surrounding majorities. Many of them avoid pork and alcohol – but some do not. None of them express their Muslim identity through visual symbols such as hijab or a beard. None of them prays regularly, and just a few visits the mosque to pray now or then. Using statistical surveys Otterbeck show how his young informants rather strong faith in God differentiate them from the majority in Sweden and Denmark, while their individualised religiosity – with a strong focus on ethics and intention – is rather typical for their time, place and age. Religion has become a private matter actualized at home with the family or through visits with relatives in their counties of origin.

In their everyday life in the larger community Islam is not as present. But, Otterbeck emphasizes, because of their ethnicity they are identified as Muslims by the surrounding society – while they are expected not to use Islam as a standard impinging on their behaviour or values. They are forced to live with expectations and demands which differentiate them from their ethnic Swedish and Danish peers.

Media and Public Perception of Islam

Most representation of Islam and Muslims in the media and other important areas of social discourse, writes Larsson and Sander (2009:211), “appear one-sided, ethnocentric, sensational and derogatory, confirming rather than challenging negative stereotypes, clichés and prejudices.” The general picture (regarding Sweds perception of Islam and Muslims), Larsson and Sander conclude, “is quite easy to summarize: the percentage of negative responses has varied from fifty to seventy-five percent, and the percentage of positive responses has varied from five to almost fifty percent.” (Larsson and Sander 2009:215f). They base this claim on a rather large body of research.33 The general opinion among Swedish scholars is that the media, as well as the popular discourse on Islam and Muslims in Sweden, promotes an essentialistic notion about Islam, allowing generalizing about Muslims as a homogeneous group. This has been recognized and acknowledged in recent media reports about Islam and Muslims in Sweden.

The subject of islamophobia has been discussed, amongst others, by Göran Larsson in Muslimerna kommer. Tankar om islamofobi (2006), Jonas Otterbeck Islamofobi – en studie av begreppet, ungdomars atityder och unga muslimers utsatthet (2007)35 and in Andreas Malm’s Hatet mot muslimer (2009).

Most representation of Islam and Muslims in the media and other important areas of social discourse, writes Larsson and Sander (2009:211), “appear one-sided, ethnocentric, sensational and derogatory, confirming rather than challenging negative stereotypes, clichés and prejudices.” The general picture (regarding Sweds perception of Islam and Muslims), Larsson and Sander conclude, “is quite easy to summarize: the percentage of negative responses has varied from fifty to seventy-five percent, and the percentage of positive responses has varied from five to almost fifty percent.” (Larsson and Sander 2009:215f). They base this claim on a rather large body of research.36 The general opinion among Swedish scholars is that the media, as well as the popular discourse on Islam and Muslims in Sweden, promotes an essentialistic notion about Islam, allowing generalizing about Muslims as a homogeneous group. This has been recognized and acknowledged in recent media reports about Islam and Muslims in Sweden.37

The subject of islamophobia has been discussed, amongst others, by Göran Larsson in “Muslimerna kommer”. “Tankar om islamofobi” (2006), Jonas Otterbeck’s “Islamofobi – en studie av begreppet, ungdomars atityder och unga muslimers utsatthet” (2007), Andreas Malm’s “Hatet mot muslimer” (2009) and in 2010 by professor Mattias Gardell in a book entitled ”Islamofobi”.

In comparison to some other European countries the political discourse on Islam and Muslims in Sweden has been comparatively civil. Between 1991 and 1994 populist Ny demokrati got elected to using xenophobic, and in many cases islamophobic, politics. In 1993 Vivianne Franzén, leader of Ny Demokrati between 1994-1997, pronounced a fear of Sweden’s future children being forced to turn their faces towards Mecca. The -00s have seen the growing popularity of another populist right-wing party – Sweden Democrats (SD) (founded in 1988 by individuals from other nationalist, xenofobic and/or neo-nazi organizations and parties). November 19 2009, Sweden Democrats’ leader Jimmie Åkesson published an article in Aftonbladet, one of Sweden’s main tabloids, where he talked about “the dangers of Islam and Islamization”, “as the greatest foreign threat to Sweden since World War II… ” January 2010 politicians and others have been debating the possibility of banning the burqa and niqab from public space in Sweden. So far none of the governing parties are promoting a law against burqa and niqab in Sweden.

In the national elections of 2010 the Sweden Democrats was made king makers in the Swedish government. The debate on Islamism discussed above ) in which they did not want to discuss other sorts of extremism, i.e. far-right or far-left) is one of a number of examples of how they been able to put forward a negative discourse on Islam in Sweden.

In a bibliography entitled “Islam and Muslims in the Swedish Media and academic research : with a bibliography of English and French literature on Islam and Muslims in Sweden”, Göran Larsson concludes that:

“while public debates and the media have both been occupied with preecceptional cases of violence, the academic study of Islam and Muslims in Sweden has mainly focused on questions such as organizatinal streuctures, historical aspects and freedom of worship. However, both journalists and academics have neglected the fact that secularim is also present among immigrant with Muslim cultural background and that ‘Muslims’ also take part in ordinary activities that are not related to religion alone.”38”

Sources

.Wikander 1978 ↩

Ådahl 2002 ↩

Svanberg and Westerlund 2002. ↩

Otterbeck 1998 ↩

Larsson 2009, Sayed 2010 The total population, according to SCB (November 30 2009) is 9 336 487. ↩

http://www.sst.a.se/statistik.4.7501238311cc6f12fa580005236.html ↩

Larsson 2009:56, Larsson and Sander 2002:108, Larsson and Sander 2007:158f ↩

Ibid ↩

Sander 1993, 1995. Also Sander and Larsson 2007 ↩

Larsson and Sander 2007: 153 ↩

Ibid 154 ↩

Ibid 154f ↩

ibid 155 ↩

Larsson and Sander 2009:163-169 ↩

Arai et al. 1999; Behtoui 1999; Bevelander 1995, 2000; Bevelander et al. 1997; Broomé et al. 1996, 1998; Ekberg and Gustafsson 1995; Franzén 1998; Månsson and Ekberg 2000; SOU 1996:55, Ch. 8; Larsson and Sander 2009: Ch. 3:1:7 ↩

Larsson and Sander 2009 ↩

Ibid 264 ↩

Berglund 2010 ↩

Curriculum for the non-compulsory school system Lpf 94: 2006 ↩

Larsson and Sander 2009: Ch. 3.1.9 ↩

Larsson and Sander 2009: 245 ↩

Roald 2009:137-143, Klaussen 2005 ↩

http://www.muslimsdebate.com/story.php?story_id=1488 ↩

Larsson & Sander 2009:169-186 ↩

Berglund 2009, 2010 ↩

http://sydsvenskan.se/sverige/article552769/Nio-svenskar-i-fangenskap-for-terrorbrott.html ↩

Säpo 2010 ↩

News Agencies ↩

Olsson, Susanne Religion in the Public Space: ‘Blue.and-Yellow Islam’ in Sweden. Religion, State and Society, No 3, 2009 Routledge ↩

Klausen 2005:113 ↩

For litarature on mosques in Sweden see: Eva Vikström, Rum för islam – moskén som religiöst rum i Sverige. Stockholm: Riksantikvarieämbetet (2006) and Pia Karlsson & Ingvar Svanberg: Moskéer i Sverige. En religionsetnologisk studie av intolerans och administrativ vanmakt. Tro & Tanke (1995). ↩

SOU 2009:52 http://www.sweden.gov.se/sb/d/11358/a/127317 ↩

See Larsson and Sander 2009, footnote 220, also pps 224-232 ↩

e.g http://www.dn.se/opinion/debatt/var-bild-av-muslimerna-ar-praglad-av-skaggiga-man-1.1024270 and http://www.svd.se/nyheter/inrikes/tio-muslimer-tio-satt-att-tro_4061975.svd ↩

An english summary of the study is available here: http://www.levandehistoria.se/files/islamophobia_englishsummary.pdf ↩

See Larsson and Sander 2009, footnote 220, also pps 224-232 ↩

e.g http://www.dn.se/opinion/debatt/var-bild-av-muslimerna-ar-praglad-av-skaggiga-man-1.1024270 and http://www.svd.se/nyheter/inrikes/tio-muslimer-tio-satt-att-tro_4061975.svd ↩

Larsson 2006

The full text is available at: http://cadmus.eui.eu/dspace/bitstream/1814/6318/1/RSCAS_2006_36.pdf ↩