After one year and two days in Turkish prison – mostly spent in solitary confinement – journalist Deniz Yücel was set free by the Turkish authorities on February 16, 2018. The case of Yücel, a German and Turkish dual national working for the German Die Welt newspaper, had been a severe stumbling block in German-Turkish relations over the past year.

High-profile case

To be sure, Yücel was far from the only German or German-Turkish citizen caught up in the mass arrests that have been commonplace in Turkey since the 2016 coup attempt. Nor is he the last to be liberated: five German Turks continue to be held in Turkish prisons. More than any other detainee, however, Yücel became a symbolic bone of contention between the two governments.

In Germany, Yücel’s arrest on February 14, 2017, has consistently been seen as a political manoeuvre on the part of the Turkish leadership. The fact that he was held in prison for more than a year without official charges being made only served to corroborate this view.

‘Terrorism’ allegations

Among those sympathising with the Turkish government’s position, Yücel was frequently castigated as a ‘terrorist’. President Erdoğan asserted – somewhat inconguously – that Yücel was both a German spy and a representative of the Kurdish PKK organisation.

However, over the past months the Turkish side had come to moderate its tone: Foreign Minister Çavuşoğlu signalled his willingness to resolve the case and expressed dismay over the failure to mount charges. Prime Minister Yıldırım recently expressed his hope for Yücel’s quick liberation.1

Reversal of the Turkish position

Setting the journalist free thus represents a dramatic reversal in the Turkish position: In April 2017, President Erdoğan had claimed steadfastly that Yücel would “never” be liberated “as long as I am in office”.

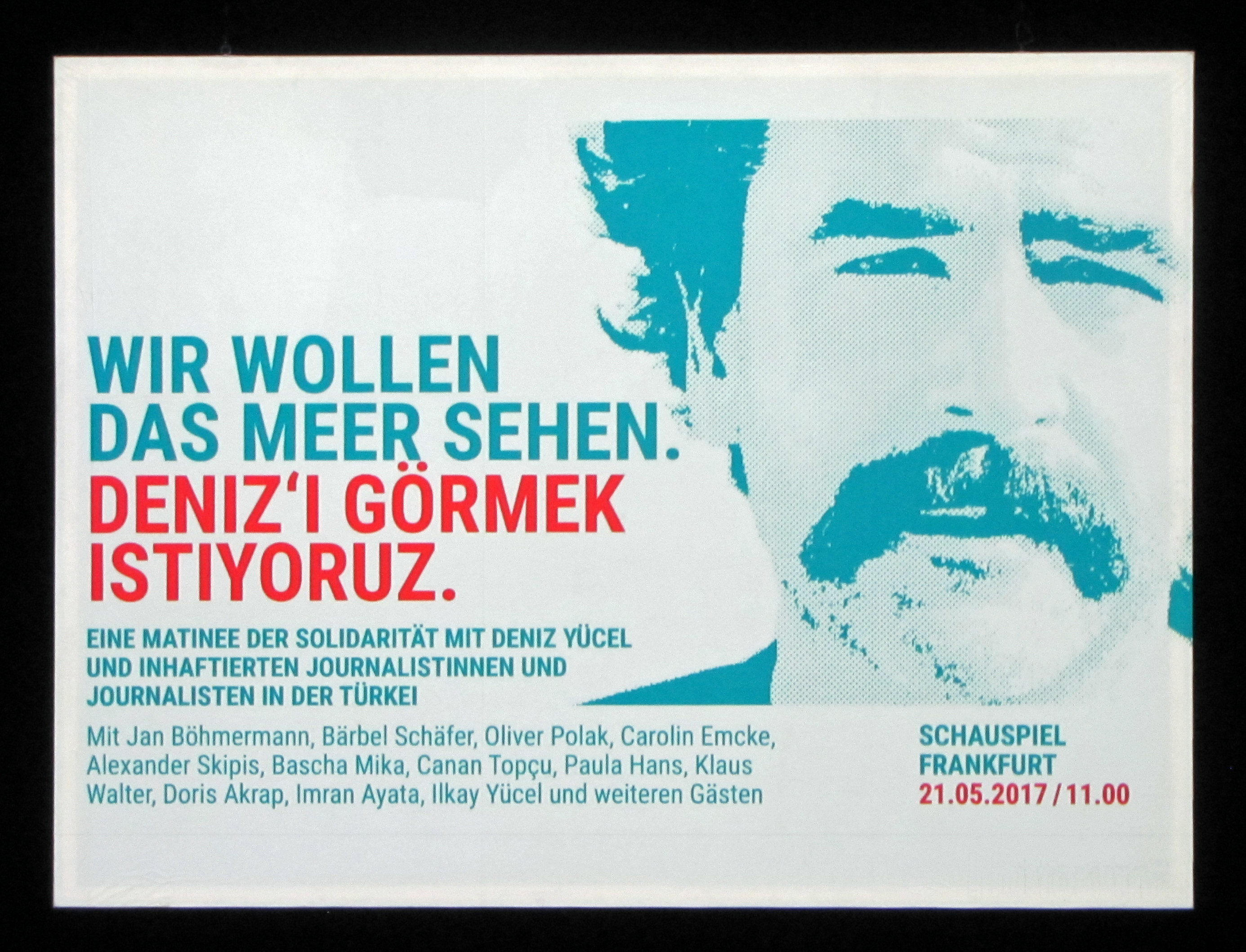

Yet the Yücel case probably came to be seen by the Turkish leadership as a burden that was not worth perpetuating through an obstructionist position. Over the past year, mobilisation in Germany in support of Yücel had been extremely strong and durable: There were public demonstrations, car parades, and discussion events; the #FreeDeniz hashtag was omnipresent; and one of the country’s most popular late night TV shows put up a picture of Deniz Yücel on stage at every broadcast.

Hoping for German tanks

As Turkey has become more and more embroiled in the conflict in northern Syria, its leadership’s attention has shifted onto new fronts. More particularly, the Turkish wish to curb Kurdish autonomy in the region has spurred the desire for better armaments – notably German tanks. Here, the continued irritations stemming from Yücel’s detention were most likely seen as too much of a detraction by Turkish decision-makers.

To be sure, German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel emphatically denied claims that there had been a quid pro quo through which Yücel’s liberation had been ‘bought’ by the German government.2 However, immediately after the journalist had left his prison cell, Gabriel’s Turkish counterpart Çavuşoğlu flouted the “mutually advantageous” idea of a joint venture involving German tank manufacturer Rheinmetall for producing 1,000 Turkish battle tanks.3

A ‘backroom deal’?

Last year, the German government drastically reduced export allowances granted to German defence and armaments producers wishing to sell their products to Turkey. Since the onset of the Turkish offensive against the Kurdish YPG militia in northern Syria virtually no further allowances were granted – a decision strongly criticised by the Turkish government.4

Against this backdrop, Sevim Dağdelen of The Left party criticised the German government for its lack of transparency in the negotiations over Yücel, as well as other German citizens detained in Turkey.5

Yücel himself had expressed his unease with any potential backroom deals being used to secure his freedom. Writing from prison, he had asserted that “I do not want my freedom to be stained by Rheinmetall’s tank deals […], nor by the extradition of Gülenist former prosecutors or putschist former officers.”6

A fraught relationship

While his freedom might have been sealed with precisely such an agreement involving Rheinmetall’s tanks, other issues in the German-Turkish relationship – notably the extradition of President Erdoğan’s political enemies – remain unresolved.

Only in early February did it emerge that Germany has granted asylum to four former military commanders wanted by the Turkish government for their leading roles in the 2016 coup attempt. Turkish negotiators had apparently offered the liberation of Yücel in return for the extradition of the alleged plotters.7

The Munich Security Conference, a high-level meeting involving policy-makers from the security and defence fields from across the world, delivered further signs of ongoing tensions in German-Turkish relations. The Turkish delegation complained that they had to share a hotel with a “terrorist” – the former chairman of the German Green Party, Cem Özdemir. Özdemir was subsequently placed under special police protection.8

Sources

https://www.suedkurier.de/nachrichten/politik/Ein-richtiger-Agent-und-Terrorist-Zitate-zum-Fall-Deniz-Yuecel;art410924,9621302 ↩

https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/interview-gabriel-109.html ↩

http://www.manager-magazin.de/politik/deutschland/panzer-altay-tuerkei-setzt-auf-deutschland-und-rheinmetall-a-1194197.html ↩

http://www.deutschlandfunk.de/freilassung-von-deniz-yuecel-fuer-mich-bleibt-die-frage-was.694.de.html?dram:article_id=410936 ↩

http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/deniz-yuecel-seit-einem-jahr-in-haft-365-ungeheuerliche-tage-a-1193199.html ↩

http://www.zeit.de/politik/2018-02/tuerkei-putsch-anfuehrer-asyl-deutschland ↩

https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/oezdemir-polizeischutz-101.html ↩