In recent years, civil society-led efforts to prevent Muslim youths’ turn to Salafism have intensified.

Often described in terms of ‘preventing violent extremism’ (PVE) or ‘preventing radicalisation’, many of these projects have attracted generous funding by state agencies. Germany is perhaps the paradigmatic case of this development: through successive government funding initiatives, the country has sprouted Europe’s largest civil society counter-radicalisation sector.1

Streetwork in Bonn

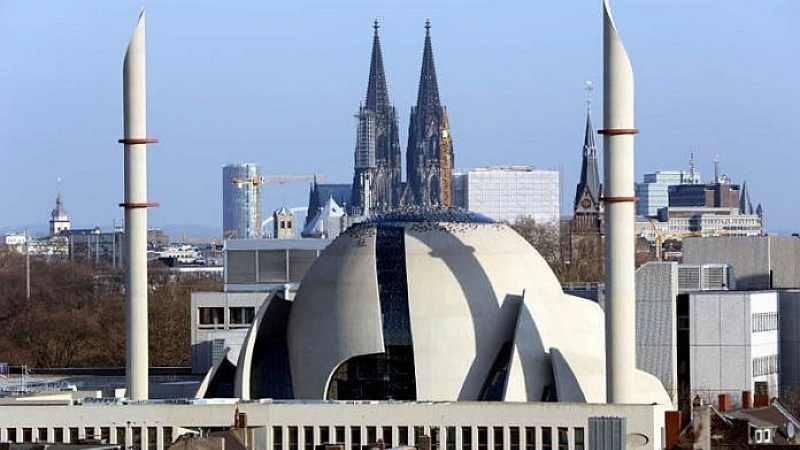

Qantara.de – a website that is funded by the German Foreign Office and, as such, also part of an overall project seeking to encourage dialogue and prevent radicalisation – spoke with activist Saloua Mohammed, a street-worker in the West German city of Bonn.2 The city has been considered as one of the major centres of Salafi organising in Germany.

The article describes Mohammed as working with “young people who have already been in contact with the radical Salafist scene”; what these ‘contacts’ consist in, concretely, is not specified. A particular concern of Mohammed’s are women returnees from the battlefields of Syria and Iraq: they have left ISIS’s crumbling caliphate and are often traumatised; some of them are also still adherents of ISIS’s worldview.

The recent re-focusing on returnees is a further shift in the unstable Salafi field: in the early 2010s, Salafis were occasionally physically present on Germany’s streets – e.g. distributing Qurans in pedestrianized shopping streets. Following a security crackdown, however, the scene has become more secretive, shifting larger parts of its activities online.

Concerns of family and friends

Mohammed paints a picture of families and friends often despairing at the seemingly inexorable turn of a loved one towards more extreme religious beliefs. She also emphasises that Muslim youth are frequently left to their own devices and disorientated, lacking people willing to listen to their concerns.

Mohammed wishes to take ‘her’ youth seriously, considering them as equal partners in a conversation. Yet it is not only this approach that sets Mohammed’s work apart from many other pedagogical interventions aimed at Muslim youth. Rather, it is also comparatively rare for social workers to offer services to adolescents (or grown-ups) who are actually part of a Salafi scene.

In fact, the plethora of civil society-led projects the German government is funding are mostly directed at Muslim youth as such – irrespective of whether they have ever encountered or developed sympathies for Salafi positions.3 This not only raises the question of these projects’ effectiveness; it also highlights the stigmatising and discriminatory side-effects that necessarily ensue when all Muslims are addressed by government-funded initiatives as potential radicals whose slide into extremism must be prevented.

Millions for counter-radicalisation

After the German government has poured millions of Euros into preventing Salafism – in 2017, a new National Prevention Programme was created that made available € 100 million in 2018 alone – it is somewhat ironic that Mohammed is working as a volunteer.

In fact, her regular job is at Caritas, the Catholic Church’s social welfare organisation. (For a lack of funding, professionalism, and legal recognition, there are no major Muslim confessional welfare services.) Her activities as a street-worker are unremunerated and arise from a personal willingness to make a positive contribution.

While her commitment to civic engagement may be seen as inspiring, it also highlights the financial precariousness of projects like hers. In fact, many practitioners complain that there are no funds available for streetwork in difficult neighbourhoods, and that many cities and regions have cut funding for regular youth centres and other social support networks. Yet it is these durable institutions that could actually offer a lasting safety net for all youth – beyond the current concern with ‘radicalisation’.

Security sector suspicion

At the same time, if organisations do obtain state funding, they are submitted to strictures of a different kind. This not only includes swaths of paperwork to satisfy the requirements of the state’s bureaucratic machine. It also directs the glaring gaze of the state’s security agencies at the recipient organisations.

In 2017, for instance, a number of case workers of the counter-radicalisation NGO Violence Prevention Network (VPN) came under suspicion of being Salafis themselves. Although disproven, these accusations quickly turned into an existential threat to the organisation: its reputation was on the line – and hence also the state funding it was dependent on.4

Thus, while Saloua Mohammed emphasises that she is routinely criticised from the far right and from Salafis for her work, there is a third player exercising considerable pressure on social workers active in the counter-radicalisation field: the state. (This should not come as a surprise, given the highly problematic surveillance tactics of Germany’s domestic intelligence agencies, as well as far-right sympathies inside Germany’s security apparatus.)

Epistemological uncertainties

This dynamic of suspicion is so powerful and so expansive, at least in part, because it is so unclear what ‘Salafism’ actually is and what counter-radicalisation initiatives are supposed to ‘prevent’. For when it comes to these fundamental terms, much conceptual confusion reigns.

The Qantara.de article straightforwardly asserts that “radical Salafists [are] ultra-conservative Muslims who interpret the Koran literally, live their faith the way it was common during the times of the prophet Muhammad and who are looking for new followers.” Their “stringent distinctions between good and evil […] evidently facilitate[…] the downward slide into extremism.”

Yet there is nothing ‘evident’ about these far-reaching assumptions, upon further scrutiny. In fact, the argumentative leap from a ‘literalist’ reading of the Qur’an to ‘extremism’ (read: terrorism and violence) remains largely unsubstantiated. As more thoughtful observers have noted, the majority of Salafis never turn to violence. And the kind of rigorous emphasis on purity characteristic of many religious currents dubbed ‘Salafi’ may also lead not to a terrorist uprising but to an apolitical retreat from a world seen as an impure cesspool of vice.

Counter-radicalisation work and the problem of legitimacy

The entire edifice of counter-radicalisation thus rests on extremely questionable epistemological foundations. Street workers such as Saloua Mohammed may be able to circumvent some of these uncertainties in practice: after all, they are dealing with concrete individuals – rather than with the abstract figure of a ‘Salafi’.

Yet as long as the very premises of counter-radicalisation practice remain so unclear and, in fact, dubious, pressing questions persist. They concern, above all, the legitimacy of the counter-radicalisation enterprise: if the diagnosis of the phenomenon to be ‘prevented’ is so murky, then what do these counter-radicalisation initiatives actually accomplish? And until what point must ‘radical’ viewpoints be tolerated rather than ‘prevented’?

Sources

Ceylan, Rauf; Kiefer, Michael (2018). Radikalisierungsprävention in der Praxis: Antworten der Zivilgesellschaft auf den gewaltbereiten Neosalafismus. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, p. 86. ↩

https://en.qantara.de/content/salafism-in-germany-battling-radicalisation-on-the-streets?nopaging=1 ↩

https://www.dji.de/fileadmin/user_upload/DemokratieLeben/Zweiter_Bericht_Modellprojekte_2016.pdf, p. 188. ↩

http://www.faz.net/aktuell/rhein-main/mitarbeiter-von-beratungsstelle-gegen-salafismus-entlastet-14935915.html ↩