Like Christian Easter and Jewish Passover celebrations a few weeks ago, in Germany the Muslim holy month of Ramadan is taking place this year in the shadow of Covid-19. This means that much of the regular festive programme is falling flat: mosques have been closed since mid-March, meaning that believers cannot pray or socialise at houses of worship. Social distancing rules render impossible shared iftars with extended family, friends, or the larger community.

Islamic organisations supportive of mosque closures

Germany’s largest Islamic associations continue to back public measures designed to slow the spread of the virus, even if it means cutting back on beloved Ramadan activities. Aiman Mazyek, chairman of the Central Council of Muslims in Germany (ZMD), asserted that keeping mosques closed remained “our religious and civic duty”.

„Gesundheitsschutz und der Schutz von Menschenleben in dieser Pandemie stellt für uns gläubige Muslime die allerhöchste…

Posted by Zentralrat der Muslime in Deutschland on Thursday, April 16, 2020

At the same time, however, for many mosque congregations the costs of lockdowns are not only of a spiritual nature: Germany’s frequently underfunded local Islamic associations are strongly reliant on donations from members to cover their basic financial expenditures; and Ramadan is traditionally the month were a bulk of these donations are collected. The lockdown is thus expected to result in a large financial shortfall for mosques, leading Mazyek as well as Burhan Kesici – chairman of the Coordination Council of Muslims (KRM) – to call for financial aid from the state.1

Differential impact of the lockdown

The fact that Muslim associations and Islamic communities are much less well protected financially than for instance Germany’s Protestant and Catholic churches highlights the tendency of the virus to reinforce pre-existing inequalities. Yet Covid-19 also has a differential impact among Muslims. To be sure, communal iftars or time spent with friends and family may be missed across the board. Yet individual testimonials collected by bento magazine still highlight massively divergent experiences of a Ramadan in times of lockdown.

On the one hand, 27-year-old Hella – a white German convert to Islam studying at the university in Hamburg – is busy organising an online iftar platform. Its aim is to ‘match’ Muslims that are stuck at home alone for virtual communal iftars. For Hella, this year’s Ramadan is also a time of intensified spiritual introspection; in fact, a somewhat beneficial side-effect of Covid-19 for her is that the virus leaves more time for quiet reflection, since many usual social events and obligations fall away.

On the other hand, 34-year-old Khan – a Bangladeshi man recently arrived in Germany – lives in a public shelter for refugees. It is forbidden to cook or take food to one’s room; and the cafeteria keeps serving meals at regular times – effectively rendering it impossible for inhabitants to keep the fast and celebrate iftar. The only possibility for Khan to enjoy a moment of festive Ramadan feeling is to head for the local train station, where he can use the free WiFi to call his parents in Bangladesh.2

Novel activities, online and offline

The current situation has spawned a search for alternative ways of finding community and spirituality during the holy month. Like Hella’s iftar matching platform, a lot of this is organised online: Muslims can listen to Quranic recitations3; and some organisations have moved their discussion groups and their Ramadan-timed activities of inter-religious dialogue online.4

Others are keeping up at least some form of ‘offline’ activism – mainly through the distribution of food: some are delivering an ‘iftar to go’ especially to elderly Muslim community members left isolated.5 Others are handing out hot meals to students, the elderly, and the poor.6

Muslims as unsolidary ‘black sheep’

Yet Ramadan under conditions of lockdown not only means newfound social solidarity. It also aggravates pre-existing quarrels and brings to the fore more long-standing fault-lines. Perhaps most notably, there is an undercurrent in the German press that accuses Muslims – and their Ramadan customs – of spreading the virus, of being hazard to public health, and of sapping the national union sacrée in the battle against Covid-19.

The reputable Der Tagesspiegel newspaper for instance accused fasting Muslims of being ‘Salafists’ – a term that functions as an invective in the German media context – and of favouring or even intentionally planning the spread of the virus by purposefully weakening their immune system through fasting.7

A similar trope of the ‘rogue’ Muslim was in evidence on the pages of country’s largest tabloid, Bild, which titled that “Churches [are] closed due to worries over Ramadan chaos”: public authorities would in principle open up Christian houses of worship, the paper maintained – yet because Muslims would behave in an unruly manner, mosques had to remain shut. And squeamish politicians were unwilling to call a spade a spade – i.e. single out Muslims as the troublesome group – which meant that all religious services had to remain banned.8

Was ist eigentlich ein "Ramadan-Chaos", liebe @BILD?

Und by the way: Kirchen, Synagogen, Moscheen haben nur aus einem Grund geschlossen: Aus Fürsorge für die Menschen. Und so kurz vor Ramadan – eine Zeit der inneren Einkehr – Gläubige gegeneinander aufzustacheln, ist asozial. pic.twitter.com/5itisVPMre

— Eren Güvercin (@erenguevercin) April 16, 2020

Screaming headlines in Bild: “Churches closed due to worries over

Ramadan chaos” and “Berlin hate preacher fleeced 18,000 Euro of

Corona help – even though he is cashing in on social benefits!”

Disputes over the call to prayer

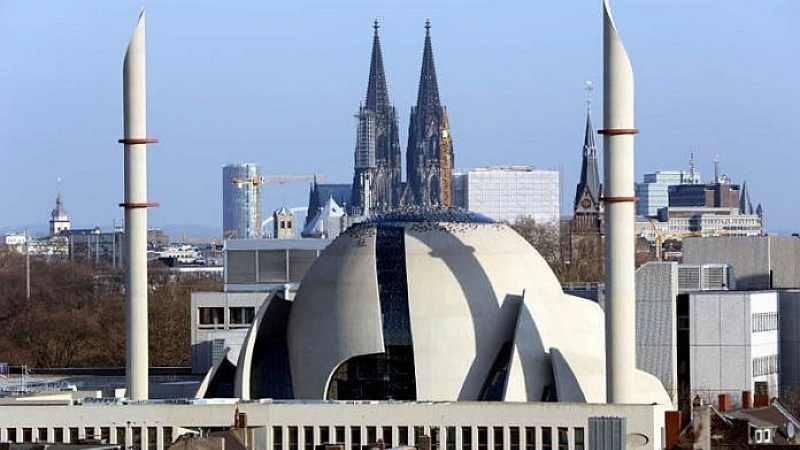

The call to prayer has emerged as another bone of contention. As a rule, mosques in Germany are not allowed to broadcast a call to prayer audible to the outside. Nevertheless, by way of spiritual support to believers of different faiths, a mosque and an Evangelical church in the Berlin district of Neukölln decided to join forces and have the Islamic call to prayer and the Christian church resound in the neighbourhood at the same time.

While the mosque remained closed to visitors throughout this attempted show of inter-religious solidarity, around 300 bystanders gathered outside its gates, for reasons of religious devotion as much as for curiosity. Authorities did not manage fully to enforce social distancing rules; the event was aborted ahead of time, and a the incident was scandalised in the national press.9

Much of the ire was directed at the mosque and its Imam. A long-time advocate of inter-religious dialogue, the mosque runs some of the more ambitious public outreach and debate forums in the city, inviting even its fiercest critics to share its podium. Nevertheless, like much of the Muslim associational landscape, it remains under observation by Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, a fact that has resulted in protracted judicial wrangling.

Plans for a gradual reopening of religious life in May

The Neukölln district has since banned further calls to prayer, falling in line with other German local administrations. While stressing the need to maintain social distancing, Burhan Kesici of the KRM asserted that having audible calls to prayer would mean a lot to believers: “In this difficult time, church bells are tolling to support people. It would have been a very nice signal if Muslim congregations across the federal territory had been allowed to make the Azan call to prayer. People would have found solace.”10

As of the end of April, amidst an overall easing of the measures imposed, German Muslims can however look forward to perhaps being able to visit their local mosque towards the end of the holy month. For instance, the federal state of North-Rhine Westphalia (NRW) – the country’s most populous region – will allow religious services to resume starting at the beginning of May.11

Burhan Kesici nevertheless remained cautious: only those mosques that could maintain social distancing standards and offer hygiene products such as disinfectants would be allowed to open, he said. Wearing masques would be compulsory; openings would be limited to one or two prayer times per day; Friday prayers would not be held; and ritual ablutions might have to be performed at home.12 For Muslims, like for everyone else, easing out of the lockdown will be a lengthy process.

Sources

https://www.welt.de/vermischtes/article207428697/Corona-Zentralrat-der-Muslime-stimmt-auf-schwierigen-Ramadan-ein.html ↩

https://www.bento.de/politik/ramadan-in-der-corona-krise-so-feiern-muslime-in-deutschland-a-e6dc4090-9809-48f4-850f-a906b8e827d0 ↩

https://dtj-online.de/solidaritaetsaktion-ditib-iftar-delivery-statt-gemeinsames-fastenbrechen/ ↩

-

Tabloids stoke fears of ‘Ramadan chaos’

Tabloids have similarly zoned in on Ramadan practices: Der Westen spoke of “unbelievable scenes” at Düsseldorf Airport, when travellers seeking to join their families in Turkey for Ramadan queued up for their flights without respecting social distancing guidelines.(( . https://www.derwesten.de/region/flughafen-duesseldorf-aerger-fuer-ramadan-reisende-daran-halten-sie-sich-nicht-id228967239.html ↩

https://m.bild.de/bild-plus/politik/inland/politik-inland/corona-lockerungen-kirchen-aus-sorge-vor-ramadan-chaos-geschlossen-70066424,view=conversionToLogin.bildMobile.html###wt_ref=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F&wt_t=1588069309540 ↩

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/300-menschen-vor-neukoellner-moschee-berliner-imam-will-interreligioese-aktion-vorerst-nicht-wiederholen/25719902.html ↩

https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article207515019/Gottesdienste-trotz-Corona-Nur-die-Moscheen-oeffnen-die-Hygienestandards-garantieren-koennen.html ↩

https://www.ruhr24.de/nrw/ramadan-2020-coronavirus-nrw-ausgangssperre-zentralrat-muslime-aiman-mazyek-zr-13697627.html ↩

https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article207515019/Gottesdienste-trotz-Corona-Nur-die-Moscheen-oeffnen-die-Hygienestandards-garantieren-koennen.html ↩