For decades now, the hijab has become a symbol of the tensions between Islam and secular European cultures [1].

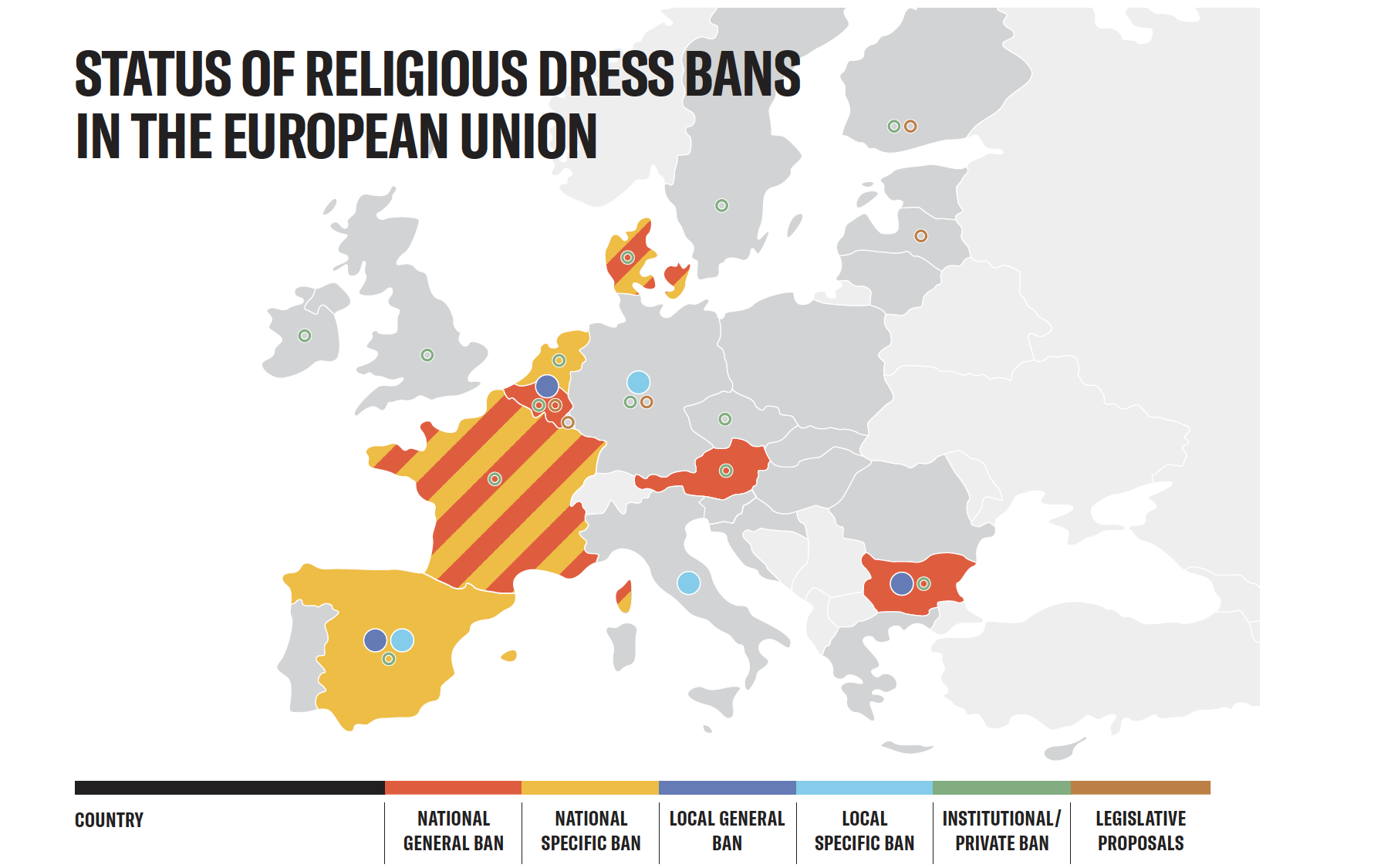

Out of the 27 EU member states and the United Kingdom, 9 countries currently enforce some type of restriction on religious dress for Muslim women. Some of these are national bans (Austria, Denmark, France, the Netherlands) [2], while other countries enforce local bans at provincial or municipal levels (Germany and Italy), and some implement both national and local bans (Belgium, Bulgaria, Spain) [See Map below].

Most of these bans, both national and local, do not explicitly target the veils worn by Muslim women, but are framed in general terms referring to items “concealing or covering the face”. Therefore, they involve prohibitions on the wearing of niqabs or other face veils that could conceal people’s identities (such as burqas) in public spaces, rather than prohibitions on hijabs. Only some specific bans directly refer to religious dress code and visible religious symbols in some settings or sectors, affecting both the wearing of niqabs/burqas and hijabs – this is the case, at the national level, of France (public employees) and Denmark (judges), and of local bans in half of the 16 states in Germany (with varying degrees of application in each) [3].

In addition, 13 EU countries have bans of niqab/burqa and/or hijab in private workplaces, particularly in private education institutions: Austria, Belgium (which has the most restrictions), Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Only 6 countries in the European Union – these being Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Poland, Portugal and Romania – do not impose restrictions on neither the hijab nor the niqab [4].

The existing bans, as well as other legislative proposals, have been justified on multiple grounds: gender equality (Belgium, France, Luxembourg and Spain), neutrality of religious symbols in public spaces (Austria, Belgium, France and Germany), security and counter terrorism (Belgium, Bulgaria, Estonia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania and Spain), integration and assimilation (Czech Republic, Finland, Ireland, and the Netherlands), and desire for homogeneity in society (across the European Union, and specifically in Hungary) [5].

National positions concerning the hijab have often influenced European-level approaches. In November 2021, for example, the Council of Europe attempted to draw attention to the anti-hijab discrimination through a campaign, organized in cooperation with the Forum of European Muslim Youth and Student Organisations (FEMYSO) – which involves 33 Muslim youth organizations across Europe –, that included a short video posted on the Council’s social media channels with the following text: “Beauty is in diversity as freedom is in hijab”, and the hashtags #celebratediversity and #JOYinHIJAB. However, the Council of Europe pulled out the campaign following French backlash, as several French politicians condemned its message arguing that the hijab does not represent freedom [6]. The French government spokesperson, Gabriel Attal, told the Financial Times that “one should not confuse religious freedom with the de facto promotion of a religious symbol,” and he called wearing the hijab an “identitarian” position “contrary to the freedom of conscience that France supports” [7].

Headscarf bans negatively affect hijab-wearing European Muslim women in their daily lives in several domains, from work opportunities to the practice of sports, and even their access to the legal system.

Hijab in the workplace

One of the major impacts of restrictions on the hijab is on Muslim women’s work opportunities. On July 15, 2021, the European Court of Justice (ECJ), based in Luxembourg, issued a ruling stating that companies in the EU can legally ban their female Muslim employees from wearing a headscarf – and any other “visible sign of political, philosophical or religious beliefs” – in the workplace, as long as the employer has a “genuine need” to present an image of “neutrality” to customers or users [8]. With this ruling, the ECJ upheld a 2017 ruling that allowed employers to adopt neutrality policies banning religious signs in the workplace, but it added the condition that employers must prove that such neutrality policy is essential for their business [9].

The ECJ case was brought to the court by two Germany female workers, a day-care centre teacher and a pharmacy cashier, who were suspended from their jobs after they started wearing hijab. The supreme EU court ruled the actions against the veiled employees were acceptable as they had been implemented in a “general and undifferentiated way” and therefore could not be considered “direct discrimination” – as another employee had also been asked to remove her cross necklace [10]. Nevertheless, there have been concerns that the ECJ ruling may facilitate discrimination against Muslim employees in workplaces across Europe. In this respect, the Open Society Justice Initiative – Open Society Foundations’ team of human rights lawyers working all over the world – stated that the ruling “may continue to exclude many Muslim women, and those of other religious minorities, from various jobs in Europe” [11]. The implications of this kind of discrimination, however, may not be easy to measure: most jobs and internships require CV including headshots, and therefore women might not end up knowing whether their rejection was due to their headscarf or to professional reasons [12].

In Germany, headscarf bans for women at work have been contentious for years, particularly regarding school teachers. In 2004, several German states’ governments banned teachers in public schools (some also included civil servants) from wearing headscarves at work – but not Christian symbols. Some of those rules were overturned in January 2015, when the Federal Constitutional Court stated that a general ban on headscarves for teachers is not compatible with the Constitution [13]. This notwithstanding, there are still some local restrictions.

Other European countries have enacted increasingly restrictive bans. France, for example, prohibited displays of religious allegiance, including headscarves, by students and school staff in March 2004 [14]. In 2010, the country enacted a national law banning the wearing of full-face veils anywhere in public. In 2018, the UN Human Rights Council ruled against France following the dismissal of a Muslim day care worker for wearing a headscarf at a private day nursery. According to the UN council, France was in breach of the international agreements on human rights by infringing on religious freedom and creating gender discrimination [15]. Due to these increased restrictions and regulations, France and Germany were listed alongside countries such as Chechnya, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, China, and areas under the Islamic State rule in a Human Rights Watch report published in March 2021, on headscarf bans and requirements [16].

Hijab in sports

Debates around what Muslim women can or cannot wear have resurfaced in France following the controversial “anti-separatism” bill, approved in parliament in July 2021 [See previous article].

On January 18, 2022, the French Senate voted to ban hijab in sports competitions, arguing that neutrality is a requirement and that headscarves can put at risk the safety of athletes. The amendment, proposed by the right-wing group Les Republicains and adopted with 160 votes in favor and 143 against, states that the wearing “of conspicuous religious symbols” is prohibited in events and competitions organized by sports federations [17]. A commission composed of members from the Senate and the lower house should gather to find a compromise on the text before it is published, meaning the amendment can still be erased.Ahead of the 2024 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games in Paris, it remains to be seen how the amended legislation will affect the tournament – in 2019, the International League for Women’s Rights (ILWR), a feminist French group, called for a hijab ban in these games [18].

The French Football Federation (FFF) bans the hijab in official matches and international games. There has been a growing pressure on the FFF to change its rules amid calls for a more inclusive practice that integrates all women, especially from the collective called “Les Hijabeuses”. Football’s international governing body, FIFA, lifted its hijab ban in 2014 [19].

Hijab in courts

In Belgium, Muslim women no longer have to take off their headscarves in the courtroom, following a law of November 28, 2021, that amended Article 759 of the country’s Judicial Code [20]. This follows the case of a Muslim woman, Mrs. Lachiri, who in 2007 was denied access to a court hearing because she was wearing a headscarf. In 2018, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled that there had been a violation of Article 9 (freedom of thought, conscience and religion) of the European Convention on Human Rights [21]. The 2021 amendment is seen as the solution to the issue raised by the Lachiri ruling, and to ensure that similar cases do not reoccur in the future [22].

In the UK, the first hijab-wearing court judge in the country was appointed in May 2020 [23]. She told BBC that she had “broken that stereotype” of what most people think judges look like, and she encouraged others in any profession to “aim high” and “break the mold”.

Conversely, in Germany, the Federal Constitutional Court rejected in February 2020 a petition from a trainee lawyer in the state of Hesse, who objected to the hijab ban in Hessian court houses [See previous article]. The Court defended the ban, arguing that it is necessary for the sake of “neutrality in ideological and religious terms” [24].

Human Rights Watch has warned of the risk of social marginalization and isolation of Muslim women associated with bans on clothing. In July 2021, a Senior Researcher of this organization’s Women’s Rights Division stated that “rather than helping dismantle patriarchal norms that underpin control of women’s bodies and behavior, such prohibitions can feed them”. This statement concluded that “Muslim women shouldn’t have to choose between their faith and their jobs” [25].

By Ada Mullol