The majority of the Muslims living in Denmark are first and second-generation immigrants from Muslim-majority countries. The Muslim immigration to Denmark has three phases. In the 1960’s and 1970’s foreign workers came to Denmark. Most of the workers came from Turkey, former Yugoslavia and Pakistan. Most of the immigrants were single males who were planning on working in Denmark for some years, sending the money home and return home when enough money was earned. In November 1973 the government halted free immigration which meant that only refugees could obtain permanent permit of residence in Denmark (Mikkelsen 2003, 11). However the foreign workers who were already in Denmark and permitted to stay could to be reunited with their families. A lot of the foreign workers chose to live in Denmark with their families instead of moving back to their country of origin. This is the second phase of immigration. The third phase of immigration characterizes the asylum seekers. Denmark accepts around 500 refugees through UNHCR each year 1. In the 1980s most Muslim asylum seekers came to Denmark from Iran, Iraq, Gaza and the West Bank and in the 1990s Muslim asylum came mostly from Somalia and Bosnia (Mikkelsen 2008).

As of January 2009, the total population of Denmark is 5.5 million 2 ; of this population, 526,036 (9.5 %) are immigrants. In Denmark it is not legal to register individuals’ religious affiliation. It is therefore not possible to say exactly how many Muslims there are in Denmark, but the estimated number is 175,000-200,000, making up 3.7% of the total Danish population (Ministry of Refugees, Immigration and Integrations Affairs, Facts and Figures, July 2009, 7).

Labor Market situation of selected ethnic minorities and total population in Denmark

| Country of Origin | Labor Market Participation % | Unemployment % | Hourly wage (DKK) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 76 | 6 | 278 |

| Turkey | 62 | 18 | 171 |

| Iraq | 38 | 27 | 138 |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | 57 | 13 | 177 |

| Other non-western | 56 | 28 | 165 |

Research by state employment agencies and Danish think tanks provides very little information about Muslims in the labor market, because ethnicity is often explicitly kept out of surveys conducted by the national bureau of statistics (Danmarks Statistik), state-subsidized insurance associations, and labor union (OSI Report 2007, 19).

There are indications that Muslims do not excel to the same degree as native-Danish in the job market. According to the Open Society Insititute (OSI) Report, the majority of ethnic minorities possess less skills and qualifications that are valuable in the workplace. However, even when ethnic minorities possess the same skills and education as their native peers, they are not on equal footing (Rezai & Golo 2005). Research by Tranæs & Zimmerman also found that discrimination is crucial factor in immigrants’ experiences with the labor market; how exactly such discrimination is manifest, such as which groups are much affected and in what types of employment scenarios is discrimination still visible, remains largely unknown (OSI Report 2007). The one factor that has received some attention by academics is immigrants’ access to networks-both within their own national and ethnic groups, as well as across ethnic boundaries (Mikkelsen 2001, Dahi & Jacobsen, 2005, Jagd 2004).

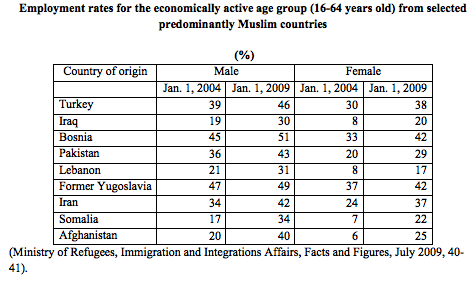

Research by the Ministry of Integration explores employment rates of immigrants based on nation of origin:

A review of the labor-market integration of ethnic minorities in Europe carried out by the Institute for the Study of Labor, collected labor-market data on minority groups in Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and the UK. These data show that the labor-market participation rate among groups that are predominantly Muslim (Turks, Moroccans, Iraqis, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis) is lower than that of the majority population. The review concludes that ethnic minorities “typically have significantly higher unemployment rates, lower labor income, and they are less likely to find and keep their jobs than the majority population” (OSI Report 2009, 109).

[TABLE=41]

When it comes to hiring, it was found that chances of an applicant being called for a job interview varied by a ratio of 1:32 depending on whether the applicant used a typically Danish name or one suggesting a Turkish, Arab or Pakistani background (OSI Report 2009, 120). In the Eurobarometer Survey 26 per cent of respondents believed that an expression of a religious belief would put a job applicant at a disadvantage. The results varied across different EU states, with the visible expression of religious identity cited as most likely to disadvantage a job applicant in Denmark (65 per cent) (OSI Report 2009, 121).

In the economic downturn since fall 2008 it seems that employees with a non-Danish background are doing better than employees with a Danish background. From December 2008 to January 2009 the unemployment rate increased with five percent for native Danes but only with three percent for non-western immigrants. From January 2008 to January 2009 the unemployment rate increased with 10 % for native Danes while the employment rate for immigrants from non-western countries increased with two percent in the same period. As explanation researchers within the field suggest that during the economic upswing in 2006 and 2007 Danish employers hired non-western immigrants and found out that they are a stable and reliable workforce. Therefore they are not the first to get fired in times of economic crisis 4 .

Comprehensive data sets concerning the education outcomes and background characteristics of immigrant students are scarce in Denmark. However, OECD has collected relevant data in the OECD Reviews of Migrant Education.

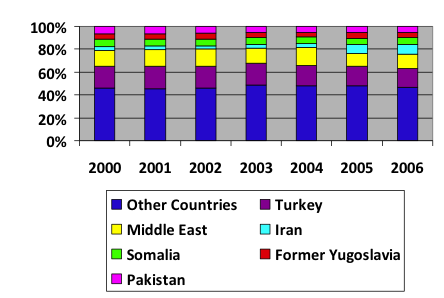

Students with a non-Danish mother tongue now make up 10% of the student population, with the largest groups coming from Turkey, the Middle East, Iran, the former Yugoslavia and Pakistan. Immigrant students are distributed unevenly across Denmark, with a quarter of all immigrants attending schools in just four municipalities (Nusche, Wurzburg & Naughton 2010, 7). National and international studies show that, compared to their native Danish peers, immigrant students on average leave compulsory education with significantly weaker performance levels in reading, mathematics and science. Students with less advantaged socio-economic backgrounds and those with a non-Danish mother tongue face the greatest challenges in achieving good education outcomes. On completion of the Folkeskole (primary and secondary lower school), students progress to the youth education sector. Immigrant students are more likely than native Danish students to go to the VET sector, which qualifies primarily for access to the labor market. Overall, of those students who start a VET program, 51 % are expected to complete the program. Among the immigrant students, however, only 39 % of those who started are expected to complete their chosen VET program. Completion rates are greater for immigrant women at 47% compared to 30% for men (Nusche, Wurzburg & Naughton 2010, 7).

(Nusche, Wurzburg & Naughton 2010, 17)

Important steps have been taken in Denmark in recent years to adapt and update teacher training for diversity. However, the OECD finds take-up of such training remains insufficient and uneven. To enhance the capacity of school level professionals to cater to the needs of all their native and immigrant students, OECD finds it essential to professionalize school leadership through better training, improve the pedagogical skills of teachers necessary to meet the needs of heterogeneous classrooms, and recruit high quality teachers including those from immigrant backgrounds (Nusche, Wurzburg & Naughton 2010, 7).

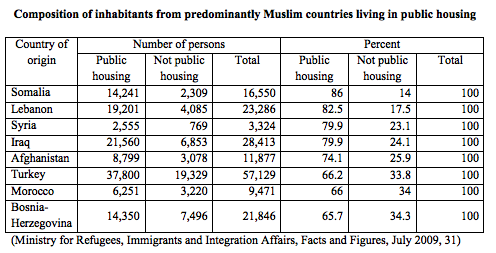

In Denmark, two-thirds of the ethnic-minority populations live in municipalities that account for only 10 per cent of the general population (OSI Report 2009, 134). 54 % of immigrants from non-western countries live in public housing in comparison only 14 % of native Danes live in public housing. Over 80 % of immigrants from Somalia and Pakistan live in public housing.

In Denmark, 27 per cent of minority respondents in one survey said that they faced discrimination in housing. These complaints centered on being overlooked in housing allocations, especially in private housing corporation waiting lists. Discrimination in housing was also highlighted in the European Commission on Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) report on Denmark (OSI Report 2009, 143).

Religious freedom is guaranteed by law in Denmark, and as of March 2010, 21 different Muslim religious communities had status as officially recognized religious societies, which give them certain tax benefits 5. The recognized Muslim religious communities are: Islamic Cultural Center, Muslim Culture Institute, Muslim Cultural Institute, Islams Ahmadiyya Djama’at, Det Islamiske Trossamfund (The Islamic Society in Denmark), Minhaj Ul-Quran International Denmark, Det muslimske kulturcenter (The Muslim Cultural Center), Den Islamiske Verdensliga (Muslim Worldliga), The Islamic Center for E.C., Aarhus Islamiske Trossamfund (The Islamic Society in Aarhus), Pakistan Islamic Welfare Society, Kulturforeningen for folk fra Irak (The Cultural Association of the People of Iraq), Islamic Center Jaffaria, Shiamuslimsk Trossamfund Danmark (The Shiamuslim Society in Denmark), Den Islamiske forening af Bosniakker i Danmark (The Islamic Society of Bosnians in Denmark), Islamisk Kulturcenter Amager (Islamic Cultural Center of Amager), Foreningen Ahlul Bait i Danmark (The Association Ahlul Bait in Denmark), Dansk Tyrkisk Islamisk Stiftelse (Diyanet), Det Islamiske Forbund i Danmark (The Islamic league in Denmark), Det Albanske Trossamfund i Danmark (The Albanian religious community in Denmark), Moskeforeningen i København (The Mosque Association in Copenhagen).

Unlike the majority of countries in the West, Denmark lacks separation of church and state, resulting in economic advantages for the Church of Denmark not shared by Muslim or other minority communities. However recognized religious societies are compensated by tax benefit. Muslims constitute the second largest religious community in Denmark after the Lutheran Protestant Church.

The Evangelical-Lutheran Church (The National Church of Denmark) is the official church of Denmark. All other religious groups in Denmark fall into one of three categories: approved, recognized, or “other religious communities”/“societies of a religious character.”

Historically, many religions in Denmark have been either “approved” or “recognized” by the Danish government. The 1969 Marriage Act marked a turning point in legislation regarding official recognition of religious institutions: prior to the 1969 Marriage Act, eleven religious communities had been approved by “recognition” by royal decree. Following the Marriage Act, which came into effect on 1 January 1970, official recognition came in terms of “approval” and included fewer privileges than “recognition.”

These concepts are similar except that “recognized” religious have additional, yet “quite small” 6 differences: ministers of “recognized” religions are by extension also approved by royal decree, these religions name and baptize children with legal effect, and they maintain their own church registers and can provide official certificates based on information from their registers. All other rights of “recognized” religions are shared by “approved” religions. These rights include: they are allowed to conduct ceremonies such as marriage with legal effect; second, under the Aliens (Consolidation) Act of September 2006 7, they have the right to residence permits for foreign preachers 8; and third, member of these communities to deduct contributions to the community from their taxable income.

Since 1970, more than 100 religious communities have been approved. The number of religious groups “approved by the Danish government has increased exponentially over the past several years. In the thirty year period between the passing of Marriage Act (1969) and 2001, 57 groups had received approval 9. That number has almost doubled to over 100 as of 2006 10.

The criteria for approval have been laid down on the basis of the legislative history behind the Marriage Act. They relate to the size, orderliness, and likelihood of continued existence of the religious community. A standing advisory committee was created in 1998 to monitor approved religious institutions and guarantee that they still meet approval criteria. This body is independent of the Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs and its members hold expertise in religious sociology, religious history, law and theology 11.

According to the Minister of Ecclesiastical Affairs, burning of the Koran “may constitute a criminal offence and result in a prison sentence” 12.

There are 179 members of the Danish national parliament and currently (March 2010) four MP have Muslim background: Naser Khader (Conservative People’s Party), Yildiz Akdogan (The Danish Social Democrats), Kamal Qureshi (Socialist People’s Party) and Özlem Sara Cekic (Socialist People’s Party). No individuals with Muslim background were elected to the European Parliament. There are several Muslim members of the local councils with most in the bigger cities.

Naser Khader was a Social Liberal Party MP from 2001 until May 7, 2007, when he split from the party to form the party “New Alliance” with Anders Samuelsen (Social Liberal Party) and Gitte Seeberg (Conservative People’s Party). The New Alliance wanted to be a right wing alternative to Venstre and Conservative People’s Party whom they meant were too influences by Danish People’s Party. New Alliance sky rocketed in the polls but at the national election in November 2007 they only gained 5 seats. Naser Khader’s lack of being able to communicate the party’s policy clear and understandable is regarded as a main reason. January 5, 2009 Naser Khader left New Alliance and March 17, 2009 he joined Conservative People’s Party as MP. He is the party’s spokesperson for Integration Affairs and Foreign Affairs 13. Khader is a prominent advocate in Denmark of the compatibility of Islam and Democracy. In response to the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy, which began after the September 30, 2005 publication of offensive images of Muhammad in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, Khader established a new organization, Moderate Muslims (see the “Media Coverage and the Jyllands-Posten Cartoon Controversy” section below). The organization was soon after renamed Democratic Muslims.

Yildiz Akdogan was elected to parliament in November 2007 and is the Social Democrats spokesperson for matters regarding IT 14. She is the chairwoman for the network ‘Turkey in the EU’ and she writes for the Danish-Turkish newspaper ‘Haber’. She is one of the founders of Democratic Muslims (see the “Muslim Organizations” section below) and is the organizations spokesperson 15.

Kamal Qureshi was elected to parliament in November 2001. He is a doctor of education and has been positioned as such in Iraq in 2003 with the Danish charity DanChurchAid. Kamal Qureshi is known for speaking up for homosexuals’ rights and for bringing mothers’ and fathers’ unequal visitation rights in relation to divorce into focus. In 2003 and 2005 he was elected politician of the year of the National Association for gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transsexuals 16. In 2007 and 2008 several newspaper articles accused Qureshi of fraud regarding renting an apartment. The police investigated the case but found no evidence that Qureshi was guilty of fraud. In February 2008 the Danish newspaper Ekstra Bladet wrote that Qureshi had cheated in order to pass his medical exam 17. Qureshi denied this. However he was relieved as Socialist People’s Party’s spokesperson for equality and health, apparently to give him time to handle the charges 18. No legal charges were put forward. In 2008 he regained his position as Socialist People’s Party’s spokesperson for equality and he is now also the spokesperson for human rights 19.

Özlem Sara Cekic has been a member of Socialist People’s Party since 2001 and was elected to parliament in November 2007. She is trained as nurse and was in 2003 elected member of Danish Nurses’ Organization as the first person with an immigrant background. She is engaged in the work for diversity in the health care sector and for recruiting nurses with an immigrant background. She has participated in several TV programs on integration and has written the autobiographical book ‘Fra Føtex til Folketinget’ (From Føtex (a supermarket) to the parliament). She is the Socialist People’s Party’s spokesperson for psychiatry and social affairs 20.

Although there are a number of Muslim organizations in Denmark, none represents the entire community in relations with the state. Muslim groups have called on the government to support the establishment of a democratically elected national council to represent Denmark’s Muslims, but unlike the governments of other EU countries, the Danish government has not to date supported this effort 21.

The status and legitimacy of Muslim organizations in Denmark is a complex and controversial subject. While the majority of Islamic groups in Denmark represent relatively small local communities 22, the most visible Muslim organization are those that have been central players in national debates about Islam in Denmark and they are therefore associated with Denmark’s most recent controversies. The Jyllands-Posten cartoon controversy was by far the most formative event for Muslim organizations in the past decade. This event, which took place between September 2005 and March 2006, began with the publication of twelve offensive cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten and at its height, put the Danish government in the middle of an international controversy (for more information on the Jyllands-Posten cartoon controversy, see the “Media Coverage” section below). Three organizations in particular received exceptional media attention: the Islamisk Trossamfund (the Islamic Society in Denmark), the Danish-based European Committee for Prophet Honouring (ECPH), and the Democratic Muslims.

Islamisk Trossamfund (IT) 23 and the ECPH are both at odds with the Danish government after members of these organizations worked to internationalize the 2005-2006 Jyllands-Posten cartoon controversy. Since the controversy, the government has targeted members of these groups for deportation and censorship 24. Leadership within IT, including imam Ahmad Abu Laban and spokesman Ahmad Akkari, played a prominent role in the internationalization of the cartoon controversy despite efforts by the Danish government to keep the affair contained. Although Abu Laban claimed in February 2006 that he had no intention of making the Jyllands-Posten cartoons anything more than an internal Danish conflict 25, an 2006 paper by Anders Rudling documents how Abu Laban and Akkari contributed to the internationalization of the controversy by circulating a 43-page manifesto to political and religious leaders and media in the Middle East 26. Although the government does not recognize them as a representative voice of the country’s Muslims. During the cartoon controversy, the Danish news publication Ekstra Bladet reported that Abu Laban’s estimated support was likely closer to 5,000-15,000 Danish Muslims, and not 200,000 as he had estimated 27. Abu Laban passed away on February 11, 2007.

Research on Danish Muslim organizations has suggested a connection between IT and the Wahabism of Saudi Arabia 28. This is the case insofar as the IT’s political positions (for example, the organization’s vehement resistance to the publication of images of the prophet) have been consistent with Salafi and Wahhabi doctrine. Salafism and Wahabism are both Sunni movements that place emphasis on Qur’an and the imitation of the Prophet Mohammed and the first generation of the companions of the Prophet and are culturally conservative. Salafism is the traditional theology endorsed by the Saudi state.

During the height of the controversy (Fall 2005 to Spring 2006) former IT spokesman Ahmad Akkari also served as spokesman for the European Committee for Prophet Honouring (ECPH). The ECPH has been referred to in the press as the “umbrella group that represents 27 Muslim organizations that are campaigning for a full apology from Jyllands-Posten.” News coverage during the controversy does not clarify the relationship between IT and The ECPH, although Akkari is referred to as spokesman for both of these organizations in articles from this period. There is also no coverage of the ECPH forming, but the first publicized reference (in English) to Ahmad Akari as spokesman for the group was in a February 6, 2006 article in The Guardian, when he made public the group’s intentions to press charges against Jyllands-Posten. Media coverage speaks of 27 Muslim groups filing a defamation lawsuit against Jyllands-Posten in March 2006, represented by lawyer Michael Christian Havemann 29. This is the same number of groups (27) reportedly represented by Akari’s ECPH, whereas Islamisk Trossamfund claims to represent 29 organizations (Rudling 2006).

On the other end of the political spectrum the organization ‘Democratic Muslims’ was founded in February 2006. The organizations’ first official activism took place on February 13, 2006 when they met with the Danish Prime Minister for talks to defuse the crisis 30. The Democratic Muslims Advocate peaceful co-existence between Islam and democracy. According to Naser Khader, one of the organization’s founders, the organization’s mission is to facilitate debate within the Danish Muslim community and create space to explore the compatibility of Islam and democracy, as well as Islam and freedom of speech 31. From the beginning Democratic Muslims experienced huge support and a lot of Muslims wanted to become members and support the organization. However the organization never succeeded in establishing a proper administration and the members were not registered 32. Soon after the establishing of Democratic Muslims the organization experienced heavy internal debate on core issues on whether it should be allowed to criticize the Qur’an 33. This led to members leaving the organization. After the Muhammad Cartoon Crisis cooled of the level of activities of Democratic Muslims have been on a minimum. Today the organization doesn’t play any role in the Muslim community or Danish politics and Democratic Muslims is widely regarded as a dying organization.

In 2006 another Danish Muslim organization was established. The Muslim Council of Denmark was founded in September 2006 and is an umbrella organization representing 14 Muslim associations with a total of around 35.000 members 34. The Muslim Council of Denmark marks a new trend in Denmark. Earlier most of the Muslim organizations in Denmark have only represented one ethnic group but the Muslim Council of Denmark represents associations with members of different ethnic origin such as Afghan, Pakistani, Albanian and Turkish 35. The Muslim Council of Denmark’s’ mission is to represent a broad range of Muslims in Denmark and act as a common voice for Danish Muslims. The Council wishes to support activities that promote active, informed citizenship and greater participation in the Danish democracy and society 36. It also wishes to act as mouthpiece between the Danish Muslim community and the Danish authorities. At the moment the council is acting as the municipality of Copenhagen’s Muslim partner in a large-scale project of building the first purpose build mosque in Copenhagen 37. In February 2009 the organization experienced heavy attention from the media. The Minister for Welfare, Karen Jespersen, said that [i]“leading members of the council are extremists who prefer a Qur’an based society instead of a secular democracy”[/i] and she said that it was naïve of the municipality of Copenhagen to use the council as its Muslim interlocutor. The mayor for Integration in Copenhagen defended the city’s collaboration with the council by saying: [i]“It is dangerous if one demonizes as big a group as the Muslim Council of Denmark represents. I do not have any reason to believe that Abdul Wahid Pedersen and Zubair Butt Hussain are extremists. It is problematic that we get a debate about extremism every time an organization tries to unify the Danish Muslims”[/i] 38 . A big challenge for the Muslim Council is to get funding enough to run an effective organization. In order to be 100 % independent the board have chosen not to receive any funding from abroad. At the same time the Danish state doesn’t support religious organizations that are not recognized as religious communities (see the section “State and Church” above for a definition of the terms). The Council therefore has to rely on member fees.

Yet another Muslim Organization has seen the light of day in the recent years. In March 2008 the organization Danish Muslim Union was founded. Also the Muslim Union wants to be a unifying organization for Muslims in Denmark. The organizations works to strengthen the Danish Muslim community and the Muslim identity and it provides counseling for members, the Muslim community in Denmark and the Danish authorities 39. However, the organization is not very active in the public debate and it seldom comment on issues relating to Danish Muslims. Like the Muslim Council of Denmark the Danish Muslim Union is an umbrella organization representing 39 organizations with members from different ethnic groups 40. How many individual members the Union represents is unknown.

Public school religious education explores a number of different religious traditions but is primarily focused on Christianity. Parents can request that their children not take part in these classes. Muslim organizations have suggested that there should be cooperation between the Ministry of Education and their organizations in the curriculum development, but as of this writing, this had not yet taken place.

Denmark also allows religious communities to establish private schools, which can receive state funding of up to 85% of the budget if the curriculum and practice meet state guidelines. In 2002, the guidelines were amended to ensure that schools prepare students to “live in a society characterized by freedom and democracy.” At the same time, regulation and supervision were increased, and private schools were required to hew more closely to the public school curriculum. This caused protests among the independent schools.

There are fifteen Islamic Schools in Denmark which is approved by the Ministry of Education 41. State funding covers up to 60 % of “free schools’” costs. The remainder of the schools’ costs is paid monthly by parents 42. About half of the Islamic schools in Denmark are located in Copenhagen.

Security, Immigration and Anti Terrorism Issues

The Danish government has enacted some of the most restrictive immigration laws in Europe. In November 2001 a center-right coalition took over after nine years of Social Democratic ruling. In 2002 the government (consisting of the two parties The Liberals and Conservative People’s Party) together with Danish People’s Party enacted a new law for immigrants. The law makes it easier to reject asylum claims, limit residence application and family reunification 43, as well as social benefits for refugees and foreigners. A much discussed part of the law is that non-Danish citizens must be at least 24 years old to marry. This rule should counter forced marriages. Furthermore the resident spouse must show economic capability to support both persons of the couple and suitable accommodation is also demanded (§ 9 in the Danish Law of Immigration).

Between 2000 and 2006, there have been four significant pieces of Danish legislation related to immigration. The Aliens (Consolidation) Act of September 1, 2006 made family reunifications more difficult for immigrant families and made it easier for the government to deny entry or expel immigrants 44. The Aliens Order of October 5, 2005 clarified existing legislations and put further restrictions on the issuing of passports, visas, work permits, and residence permits 45. Act No. 375 on Danish courses for adult aliens clarified issues of structure, curriculum, financing and implementation of the Danish citizenship courses 46. Finally, the Act on Equal Treatment of June 29, 2000 explicitly forbids discrimination on racial or ethnic terms and designated the Danish Institute for Human Rights as an official organization to monitor and make recommendation to combat discrimination and promote equal treatment 47.

Two significant pieces of legislation related to terrorism have also come into effect since 9/11. In June 2002, a package of laws called L35 were passed by the Danish parliament to combat international terrorism. The law gives police greater powers of surveillance, which can be used against Muslim individuals and groups. The law allows for the tapping and monitoring of emails without former permission of a magistrate, increased resources to use secret informants. It requires telecommunication companies and internet providers to record all internet traffic and mobile telephone communication.

In June 2004, the Danish Parliament passed the so-called “Imam Law”, which would require religious leaders to speak Danish and respect “Western values” 48 such as democracy and the equality of women 49. Further legislation gave the Danish government the right to reject “foreign missionaries” who espouse radical views. Although Danish constitutional law does not allow the mention of religion, the bill was widely viewed as being targeted at Muslims.

In May 2009 the parliament enacted a law which forbids judges to wear any religious or political symbol in court 50. The judiciary was voicing its principally opposition to the legislation and the law is widely regarded as way of avoiding Muslim women wearing hijab as a judge, however there has to date not been any Muslim judges wearing hijab in Danish courts.

In the fall 2009 FBI and the Danish Intelligence Service arrested two men whom they suspected of planning terrorism against the head quarter of the newspaper Jyllands-Posten which first published the Muhammad cartoons. David Coleman Headley and Hussain Rana, both residing in the US, are charged with plans of blowing up Jyllands-Postens headquarter and killing cartoonist Kurt Westergaard and editor Flemming Rose. Furthermore they are charged with being part of the terrorist attack in Mumbai in November 2008. The trial takes place in the US 51.

Denmark has an anti-discrimination law, Criminal Code Article 266b, which prohibits dissemination of racist statements and racist propaganda. Article 266b criminalizes insult, threat or degradation of persons, by publicly and with malice attacking their race, color of skin, national or ethnic roots, faith, or sexual orientation. When a number of Muslim organizations filed complaints with Danish police against Jyllands-Posten, they claimed that the newspaper had committed an offence under 266b and Blasphemy Law (Criminal Code Section 140) (for more information on the Jyllands-Posten cartoon controversy, see the “Media Coverage” section below). The Blasphemy Law prohibits disturbing public order by ridiculing or insulting the dogmas of worship of any lawfully existing religious community in Denmark. Public authorities, first the Regional Public Prosecutor and later the Director of Public Prosecutors in Denmark, found no basis for concluding that the cartoons constituted a criminal offence, given that in this case public interest was better served by protecting the right of editorial freedom to journalists.

The first complaint was filed on October 27, 2005 to the Regional Public Prosecutor in Viborg. On January 6, 2006, the Regional Public Prosecutor discontinued its investigation on the grounds that no criminal offense had been committed. On March 15, 2006, the Director of Public Prosecutions filed a decision supporting actions taken by the regional Public prosecutor 52. Though these legal resolutions decided in favor of Jyllands-Posten’s right to editorial freedom of expression, they also identified the need in Danish society for a respectful dialogue about Danish and Muslim values, ultimately suggesting that while the newspaper would not be censored, it also had a responsibility to contribute to a respectful climate. In its conclusion, the decision by the Director of Public Prosecutions states that statements by the Jyllands-Posten defense were “not a correct description of existing law” when they claimed that “it is incompatible with the right to freedom of expression to demand special consideration for religious feelings and that one has to be ready to put up with “scorn, mockery and ridicule.”

International organizations have been among the most active voices in condemning what they perceive to be anti-Muslim sentiment in Denmark. In the Spring of 2001, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI 2000) public its second periodic report on Denmark, which contained a number of well-documented critical remarks and recommended measure to eliminate both day-to-day discrimination as well as institutionalized discrimination against minorities in areas such as housing and the economy (OSI Report 2007, 36). The following is an excerpt from the report:

Problems of xenophobia and discrimination persist, however, and concern particularly non- EU citizens – notably immigrants, asylum-seekers and refugees – but also Danish nationals of foreign backgrounds. People perceived to be Muslims, and especially Somalis, appear to be particularly vulnerable to these phenomena. Most of the existing legal provisions aimed at combating racism and discrimination do not appear to provide effective protection against these phenomena. Of deep concern is the prevailing climate of opinion concerning individuals of foreign backgrounds and the impact and use of xenophobic propaganda in politics. Discrimination, particularly in the labour market, but also in other areas, such as the housing market and in access to public places, is also of particular concern (ECRI 2000).

The OSI report notes that the dominant political establishment (including the Social Democrats, and most media outlets, downplayed both the authenticity and validity of the report’s criticisms. Ironically, there is a growing body of scholarship about political discourse in Denmark that supports the findings of the ECRI report and documents how such alleged xenophobia and anti-Muslim sentiment appear increasingly visible 53.

Some scholars have ventured to claim that Denmark has become one of the most staunchly anti-Muslim nations in the West (Andersen et al 2006). This sentiment is also reported by domestic observers and social science researchers (OSI report 2007, 37). Two other publications have supported this perception: the first was a PhD dissertation by a Danish scholar in 2001 claimed that there was widespread cultural racism in Denmark directed particularly at Muslims long before 9/11 (Wren 2001); the second was a report by the European Monitoring Centre (EUMC) which placed Denmark on the top of the list of countries where there had been a sudden increase in racial attacks against minorities.

In addition to this documented rise in discrimination and cultural racism, there has also been a substantial increase in the number of attacks on Muslims since September 11th, 2001 (Committee on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination, United Nations, 2002). The Danish police report hate crimes to the Danish Civil Security Service (PET), but do not categorize these incidents as anti-Muslim, anti-Semitic, or anything else. In 2004, the PET database recorded 32 “racist/religious” incidents. The Documentation and Advisory Centre on Racial Discrimination (DACoRD) is a nongovernmental organization that collects information on a range of racist and xenophobic incidents. In the period between January 1 and October 13, 2005, DACoRD recorded 22 Islamophobic incidents, eight of which were also documented in the PET database 54.

Reports have shown that many Danish Muslims have had difficulties gaining access to public places such as restaurants and clubs, and women wearing headscarves have been denied transportation on public buses (ECRI Report on Denmark, 2000).

Somalis in particular have had difficulties in Denmark, being both Muslims and asylum seekers. Media and politicians have contributed to a widespread view that Somalis are not able to integrate into Danish society, and this has had a negative effect on the self-perceptions of the community. High unemployment and low hopes have led high numbers of students to drop out (ECRI Report on Denmark, 2000).

There are approximately 70 prayer rooms serving as mosques in Denmark, but none of these spaces were built specifically as places of worship (Kühle 2006). This is mostly due to divisions within the Muslim community, although recent years have seen an increase in public and political opposition to the building of mosques.

In December 2004, the Dansk Islamisk Begravelsefond (Danish Islamic Cemetery Fund) purchased property outside Copenhagen to establish a Muslim cemetery. The purchase followed several years of dispute with municipal authorities 55. September 2006, the first Muslim cemetery was opened near Copenhagen. It is owned and managed by the Dansk Islamisk Begravelsefond (Danish Islamic Cemetery Fund), a foundation composed of approximately 25 Muslim organizations and associations 56. Prior to the establishment of this cemetery, Muslims were sometimes buried in special sections of others, but generally this made it difficult to follow Muslim tradition, which encourages Muslims to be buried with other Muslims, with the body facing Mecca.

As in most of the rest of Europe, there have been some conflicts over the hijab. In 2000, the courts decided that a department store’s refusal to accept a girl wearing the headscarf to its training program constituted illegal discrimination. However, in 2003, the court decided that a supermarket which had a policy against any headgear in public positions was not acting in a discriminatory fashion. The cases hinged on the decision of whether the policy had reasonable and unprejudiced motivations. These decisions have been upheld by the Danish Supreme Court.

The Danish People’s Party has suggested a ban on the hijab in schools and other public places. Their proposal would prohibit the wearing of “culturally specific” headgear, but exempt Christian and Jewish culture. They argued that the hijab has a “disturbing” impact on “ordinary people” and slows integration of Muslim girls into Danish society. This proposal has not yet been brought for decision in Parliament, but the government appears to be rejecting the idea.

In August 2009 Conservative People’s Party suggested a ban on wearing burqa. A heavy debate followed and it was discussed whether it would be against the freedom of expression to ban the wearing of burqa. A commission was formed in order to investigate how many women in Denmark wear burqa. In January 2010 they presented the final report which concluded that only three women in Denmark wear burqa. The idea of banning the wearing of burqa was dropped because of constitutional and human rights concerns 57.

There are regulations on slaughter practices, but these have not proven to be too burdensome for the traditional Islamic style.

Media Coverage and the Jyllands-Posten Cartoon Controversy

Since September 2001, the coverage of Muslims has been dominated by security and terrorism. There is particular criticism of the gap between the scale of coverage given by newspapers to arrests connected to terrorism and the lack of coverage when arrested individuals are subsequently released without charge. Analysis of Danish news media found that Muslims also face stereotyping through culturalist interpretations of crimes where the perpetrator is Muslim, that is, a tendency to explain crimes committed by Muslims by reference to their religion (OSI Report 2009, 211).

PhD Brian Arly Jacobsen has researched the Danish debate on immigrants. He has found that there are similarities in the way Danish politicians talked about Jews before World War II and the way they talk about immigrants today. He concludes that the cultural and religious practice of Muslims are seen as an antipole to Danish culture 58. Other studies indicate that the daily media and the press as an institution, reduce the complexity of cultural variations within the Islamic community perpetuate stereotypes of Muslims (OSI Report 2007, 35). Studies that explore these themes include Hussain et al, 1997; Hussain, 2000b; 2002b; 2003b0; Hervik et al, 1999; Slot, 2001; Hervik, 2003; Madsen, 2000; Andreassen, 2005.

Media coverage of Muslims in Denmark has been focused on divisive controversies. After the murder of Theo Van Gogh in the Netherlands, a public Danish television station was sued by a group of Muslims for repeatedly airing his film “Submission”, which was widely regarded as offensive by Muslims 59. This episode was given media attention at the time. The most significant controversy in Denmark, however, followed the publication on September 30, 2005 of 12 cartoons in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten that caricatured Islam and the Prophet Muhammad.

The episode began with a contest for caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad by a Danish Paper responding to what was perceived as a climate of censorship surrounding coverage of Islam. Flemming Rose, cultural editor of the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, became concerned by a series of events he interpreted as censorship by the European Muslim community in the summer of 2005: the first of these was the closing of an art exhibit said to offend Muslims at the Museum of World Culture (the Världskulturmuseet) in Gothenburg. Secondly, the Tate Gallery in London cancelled an exhibit artist John Lathham that depicted the Koran, Bible and Talmud torn to pieces. A third event occurred in September when Kåre Bluitgen, a Danish children’s writer experienced difficulties locating an illustrator for a book about the life of Muhammad. Three artists turned down his offer out fear for physical repercussions and the artist who finally agreed did so only on conditions of strict anonymity (Rudling 2006, 2). That same September, a delegation of Muslims approached Danish Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen demanding that Rasmussen intervene with the Danish press to produce more positive coverage of Islam.

Rose held a competition for cartoons caricaturing Islam and the Prophet Muhammad. Twelve cartoons, selected from these submissions, were published on September 30, 2005. Muslims hold widely variant opinions on depictions of the Prophet Muhammad. Though the Qur’an makes no prohibition on the reproduction of images of Muhammad, Salafi and Wahhabi strains of Sunni Islam object strongly to the publication of representations of Muhammad (Rudling 2006, 4) 60.

Many high-profile Muslims in Denmark were outraged by the cartoon and 3,500 protests were organized in Denmark throughout early October 2005. Prime Minister Rasmussen was approached on October 12 by eleven ambassadors from Muslim countries to discuss what they argued was anti-Muslim media coverage (Klausen 2009, 63). Rasmussen refused to meet with the delegation (Klausen 2009, 65). Two Danish clerics, seeing that street protests and diplomatic gestures toward the Danish government were not effective, turned their efforts toward the international Muslim community.

In December 2005, a thirty-one year old imam named Ahmed Akkari traveled to the Middle East with a 43-page dossier of cartoons, letters and drawings. He represented the Islamic Faith Society of Denmark (Islamisk Trossamfund i Danmark) and claimed to represent 29 Danish Muslim organizations and the 170,000 to 200,000 members they represented. Abu Laban, a prominent imam in Copenhagen and leader of IT, was responsible for sending Akkari to contact religious and political leaders for help putting pressure on the Danish government. In addition to the twelve Jyllands-Posten cartoons, Akkari’s dossier also included three cartoons that had not been published in the cartoon competition yet which Akkari claimed to represent Danish attitudes toward the prophet. The addition of these cartoons later made Akkari and Laban subject to criticism that they were trying to inflame an already tense situation. These three cartoons were images of a praying Muslim being sexually assaulted by a dog, a picture of a “pedophilic Muhammad” holding hands with a young girl, supposedly his wife Fatima, whom Muhammad married when she was six and he 54. The third picture was of a Frenchman dressed as a pig for a “pig-squealing competition,” to which Akkari added the caption that “this is the true picture of Muhammad” in the Danish press 61.

Throughout December and January, protests, some of which became violent, broke out across the Middle East, and media coverage, including that by English and Western outlets, misreported that the three added cartoons were part of the original Jyllands-Posten publication 62.

On January 26, Saudi Arabia pulled its ambassador from Denmark, as did Libya on January 29. Syria called for the Danish government to punish the Jyllands-Posten “criminals” and the Organization of Islam Conference, which represents 57 Muslim states, called upon the UN for a Resolution and economic sanctions against Denmark. On January 30, al-Fatah militants stormed the Gaza EU offices and demanded an apology from the Danish government. A boycott of Danish products spread throughout the Muslim world. During this period, many protests turned violent (Rudling 2006, 12). On February 4 in Damascus, the Danish and Norwegian Embassies were attacked, and in Beirut the next day, the Danish Consulate was targeted. Crowds in Tehran attacked the Danish and Austrian embassies on February 6 63. In Europe during the following days, many Muslims also took to the streets.

On January 30, Carsten Juste, the Editor-in-Chief of Jyllands-Posten published an open letter of apology for causing offense and speaks of the controversy as the result of a grave misunderstanding.

Both Akkari and Laban were attributed with internationalizing the cartoon controversy. Pia Kjærsgaard, leader of the nationalist Danish People’s Party, accused the imams of “conducting a smear campaign against Denmark.” 64 One popular reaction in Europe was to show solidarity with the newspaper. A significant portion of the European media chose to show support of Jyllands-Posten by re-printing the cartoons. By the beginning of March 2006, the cartoons were published in 143 newspapers in 56 countries across the world 65.

In response to the boycotts by Muslim countries of Danish product, the Danish dairy company, Arla, issued a statement published in 25 Arabic newspapers explaining that they “understood and respected” the boycott of their products. Danish politicians, including the leaders of the governing party The Liberal (Venstre) and of the right-wing Danish People’s Party immediately condemned Arla’s statement as a submissive and spineless campaign 66. By March 2006, the Swedish-Danish Arla Foods had lost 500 million Swedish crowns (approximately 80 million US dollars) from the Muslim boycott. This is just one example of how the Danish economy suffered from the controversy.

Beginning in February 2006, certain events helped slowly diffuse the controversy. Abu Laban made public statements on February 10, 2006 defending Denmark as a “nice and tolerant” country and called for the violence to stop. On February 27, the European Union issued a statement that “freedom of expression and independence of the press are “”universal rights” but that they must be “exercised with responsibility”, “within the limits of the law” and with “respect for religious feelings and beliefs.” The members of the European Parliament also expressed solidarity with Denmark and condemned anti-Europe violence, especially the burning of European embassies in the Middle East 67.

The Danish government could no longer ignore the crisis. Although the government’s initial reaction in October had been to refuse to accept any responsibility for the publications of a private media entity, the government did respond in February and March in a tone that defended Danish values and attempted to address what misinformation had been spread about Danish values and legal positions on religious practice. Prime Minister Fogh Rasmussen agreed to an interview with Al-Jazeera and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark initiated an information campaign to clear up misinformation that was circulating in the Muslim media.

On March 15, the Danish Director of Public Prosecutors ruled that Jyllands-Posten was not in violation of Danish law. From that point forward, the controversy continued to cool, although the Danish foreign ministry remained on high alert and Danish export to the Middle East continued to suffer. Muslim protests continued through the spring, with select Muslim leaders issuing statements of condemnation and calling for boycotts, including one by Osama bin Laden on April 24, 2006 (Feldt & Seeberg).

In February 2008 the Danish Security and Intelligence Service arrested two Tunisian citizens and a Danish citizen who they suspected of planning to kill Kurt Westergaard, the cartoonist who drawed Muhammad with a bomb-shaped turban. Since then Westergaard’s house has been heavily fortified and is under close police protection. None the less he was attacked in his home in January 2010. A 28-year old Somali man broke in and attacked Westergaard with a knife and an axe. Police officers were also attacked by the intruder and shot him in the right leg and left hand. He was hospitalized, but not seriously injured. After the attack Danish intelligence officials said the 28-year old was connected to the radical Islamist al-Shabaab militia, sympathizes with al-Qaida, and has been under surveillance by the Danish Intelligence Service for some time 68.

In February 2010 the Danish newspaper Politiken, one of 11 Danish newspapers that reprinted the Muhammad cartoons, issued an apology to eight Muslim organizations for offending Muslims – allegedly to avoid a lawsuit. The settlement which was reached between the paper and the organizations did not, however, apologize for the printing of the cartoons, nor prevent the paper from reprinting them in the future. The eight organizations who reached the agreement with Politiken are based in Egypt, Libya, Qatar, Australia, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Palestine. Together they represent 94,923 descendents of the Prophet Mohammed. In August 2009 the groups’ Saudi lawyer, Faisal Yamani, requested that Politiken and 10 other newspapers remove the images from their websites and issue apologies along with a promise that the images, or similar ones, will never be printed again. Politiken is the only one of the 11 newspapers who has agreed on a settlement 69.

Politiken’s editor-in-chief, Tøger Seidenfaden, said he was hoping the agreement would help improve relations between Denmark and the Muslim world and that “other acts of dialogue and reconciliation may follow”. But the move was derided by other newspapers, cartoonist Kurt Westergaard and leading politicians. Other newspapers which reprinted the cartoon, including Berlingske Tidende, Kristeligt Dagblad and the original publisher Jyllands-Posten, refused to enter into the same agreement with the organizations. Jyllands-Posten editor, Jørn Mikkelsen, called it a “sad day for Danish media, for freedom of speech and for Politiken”. In 2006 Jyllands-Posten apologized for upsetting some Muslims with the cartoons, but Mikkelsen believed that Politiken’s apology crossed the line as it was made as part of a deal. Meanwhile, Westergaard accused Politiken of giving up on freedom of speech and said they had given into the fear of terror. However, professor in rhetoric at University of Copenhagen, Christian Kock said that Jyllands-Posten apology from 2006 and Politiken’s apology rom 2010 are more or less similar. None of them apologizes for printing the cartoons. They apologize for offending Muslims by doing it. The difference is that Politikens apology is part of a settlement with Muslim organizations.

Opposition leaders Helle Thorning-Schmidt of the Social Democrats and Villy Søvndal of the Socialist People’s Party called the move outrageous and said deals should not be done involving freedom of speech. But not all politicians were deriding Politiken. Leader of Danish Social-Liberal Party Margrethe Vestager thought Politiken was acting courageously by choosing dialogue rather than confrontation. Also the Danish imam Abdul Wahid Pedersen praised Politiken for the apology. He didn’t think the agreement was a threat against freedom of speech: “Politiken doesn’t apologize for printing the cartoons. They apologize for having offended some by doing it” Wahid Pedersen said 70.

Politically, the controversy put the Danish government in the middle of one of the most internationally publicized conflicts since World War II (Rudling 2006, 14). It continues to be cited by European governments as an example of the need to strike a delicate balance between freedom of expression and cultural respect.

One of the best sources of public opinion towards Muslims has been in polling done surrounding the Jyllands-Posten cartoon controversy 71. In a poll conducted by Megafon and released February 9, fifty-eight percent of a total 1,033 Danes polled said the Danish imams were responsible for the worldwide protests. Of this group, 22% blamed Jyllands-Posten and 11% blamed leaders in the Middle East. Only five percent blamed the Danish Government 72. Seventy-nine percent supported their Prime Minister’s refusal to apologize, and 62% of Danes did not believe Jyllands-Posten should apologize for its role in the controversy 73. Eighty-two percent felt that the imams had hurt efforts to integrate immigrants in Denmark, while only six percent said they were helping the process 74.

The Megafon polling also had some interesting findings about how the controversy had changed public opinion in Denmark. Regarding their changing perception of Islam, sixty-one percent said their view had become more unfavorable (Megafon, February 9). Most Danes felt their relationship with Muslim countries had been damaged. On January 27, twenty-five percent of Danes said they felt these relationships had be irreparably harmed. On February 3 (less than one week later), this number had climbed to 46% (Epinion, January 27, February 3). Fifty-six percent of Danes felt the controversy had caused the divide between Danish Muslims and non-Muslim Danes to widen. Only 3% felt the gap was narrowing and 31% said it stayed the same (Epinion, February 5). This same period of time, from late-January to early-February, also saw a significant jump in the amount of Danes’ who felt the controversy had increased the risk of a terrorist attack against Denmark. On January 31, 69% of Danes felt the risk had grown; on February 9, this number was 78% (Megafon, January 31, World Public Opinion Polling).

A February 5 Epinion poll also found Danes split down the middle when it came to the controversy’s impact on large-scale religious conflict. Forty-eight percent said they were worried the violence could lead to a war of religions, while 46% said they felt that war of that kind was overrated (Megafon, January 31, World Public Opinion Polling).

Negative perceptions of ethnic minorities in Denmark were documented in 1995 Gaasholdt and Togeby (1995). They found that 37% of Muslims would not want a Muslim for a neighbor and 64% would not want a close family member to marry a Muslim (OSI Report 2007, 34). When the same questions were asked by replacing “Muslim” with “person from another race,” the figures changed to 18% and 36% respectively, indicating that public attitudes were especially negative toward Muslims.

The official position of many scholars and members of the government is that attitudes towards Muslims have not changed significantly over the past decade. These were the findings of a study by Togeby et al. (2003) and were echoed in a 2002 report by the Ministry of Integration. Furthermore, anti-Muslim attitudes are characterized in these reports and in a study by Andersen and Tobiasen (2002), as reflections of the fact that Danes themselves are not religious and are overwhelmingly secularized and therefore harbor a general skepticism toward religious practice (OSI Report 2007, 34).

There is a second body of scholarship that holds the opposite view of Danish popular perception of Muslims-namely, that public attitudes towards Muslims have deteriorated since the late 1980s (OSI Report 2007, 35).

As it is not legal to register people’s religious affiliation there are no exhaustive data on Muslims’ political participation and religious practice in Denmark. However the National Broadcasting Company Denmark’s Radio, tried to investigate this in the campaign ‘Your Muslim Neighbor’ in April 2009 and they conducted a survey building on 523 interviews with Muslims living in Denmark. Many have questioned the quality of the survey and doubt it is representative because it only builds on answers from 523 persons. Another issue of discussion has been how to define people as Muslims. Because people’s religious affiliation is not registered in Denmark it is necessary to select the respondents by name or country of origin but an Arabic sounding name or origin from a predominantly Muslim country doesn’t necessarily mean that people are Muslim. However Senior Consultant, Anders Kragh Jensen, from the Research Institute Capacent who made the survey, thinks the survey gives an indication of the perceptions among the Muslim community in Denmark 75.

The survey shows that Muslims tend to vote center/left-wing. In April 2009 58.3% of the asked Muslims would vote for the Social Democrats. In total the center/left-wing parties would gain 89.1% of the Muslim votes. The ruling parties of the government, The Liberals and Conservative People’s Party would gain respectively 5.7% and 1.1% while Danish People’s Party would gain 4.1% percent of the Danish Muslims’ votes. The only Party who seem to get as many votes among the total population and Muslims is the Social Liberal Party with respectively 5.1% and 5.8% 76.

The survey also shows that the majority of Muslims in Denmark don’t think a Muslim woman should be veiled. 51% thinks it is unnecessary for Muslim women to be veiled while 23% thinks they should. The majority of the people who don’t think the veil is essential are men 77.

When being asked whether they sympathize with extremist Muslim organizations six percent say they sympathize more or less with Al-Qaeda, 11% say they sympathize more or less with Hizb ut-Tahrir and 18% sympathize more or less with Islamic Jihad. When being asked whether they disassociate themselves from terrorism 82% say yes. In the non-Muslim Danish population 97% mean that terrorism is unacceptable. Six percent of the Danish Muslims think terrorism can be acceptable. The Danish expert on radicalization, Jørgen Staun, said in this regard that it is important to define what terrorism is. “It could be that the ones asked have another perception of what terrorism is; maybe they think it is a fight for liberation rather than terrorism” Staun said 78. In relation to this 31% of Danish Muslim thinks the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are violations against the Muslim world while 40% doesn’t think so 79.

The survey also showed that 18% of Danish Muslims would like Sharia to be integrated into Danish Law. In Denmark it is possible to take out a so-called sharia mortgage without interest but there are no sharia councils like in the UK 80.

The right-wing think tank CEPOS has also conducted surveys of Danish Muslims’ perceptions. In February 2009 they launched a study concluding that 50% of Danish Muslims would like books and movies which attack religion banned. However the data that the study was based on turned out to be one and a half years old and collected during the heated election campaign for parliament in 2007. Many researchers found the data useless. CEPOS said they didn’t publish the data sooner because it should attract attention to their conference on “Immigration, Culture and the Liberal Democracy” in spring 2009 81.

Political and Intellectual Discourse

Anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant politics has been increasing over the last years, with anti-Muslim rhetoric becoming more prominent 82. Although most anti-Muslim rhetoric comes from far-right groups, they do have a tendency to affect the discourse from other political parties. Danish arguments over the headscarf have not been successful at the political level, but the courts have ruled that businesses may restrict their wearing in public positions (IHF 2005).

Rhetoric of a value-divide between Danes and Muslims is common within the political sphere (OSI Report 2007, 36). Social Democrat leader Paul Rasmussen (1994-2001) in 2000 spoke of a divide between “us” and “the others” and said that “it is really a problem if the Danes begin to feel strangers in their own neighborhood.” Moreover, according to Rasmussen, “everyone should accept Danish values”.

The former Minister of Interior Affairs, Karen Jespersen, expressed that same year that “I could never under any circumstance live with (the idea of) a multicultural society in which the cultures are positioned equally.” She added, “In my opinion it is wrong to juxtapose Muslim values with Danish values” 83.

International governmental and research organizations have documented growing anti-Muslim sentiment in Denmark. The European Commission against Racism and Intolerance 2001 report on Denmark identified day-to-day discrimination against minorities as well as institutionalized discrimination in areas such as housing and the economy (OSI Report 2007,36). Other international bodies have also offered critiques of the Danish climate, including the United Nations Standing Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDW), and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (OSI Report 2007, 38).

The response of leading political figures can generally be categorized in the words of former Prime Minister Fogh Rasmussen’s response to the ECRI’s most recent report (2006), calling it a botched up job not to be paid any attention to (OSI Report 2007, 39).

In February 2006, the anti-immigrant Danish People’s Party (DF) called for the government to revoke the citizenship of three leaders involved in the controversy, and to exclude them from integration dialogue because of their involvement in “internationalizing” the cartoon controversy. The three individuals targeted by the DF were Ahmad Akari, former spokesman of the Islamic Society of Denmark and spokesman (as of February 2006) of the ECPH; Mahmoud Al-Barazi, head of the Muslim League in Denmark; and imam Mohammad Al-Khalid Samha, a member of the ECPH and leader of the Danish Muslim delegation who visited Muslim countries. These Muslims have complained that threats of deportation are the opposite of what Denmark needs: according to Imam Mohammad Al-Khalid Samha, a member of the European Committee for Prophet Honoring and leader of Muslim delegation that is attributed with internationalizing the conflict, “We are in a dire need now to open a direct dialogue to listen to each other without barriers.” Moves by conservatives, therefore, are perceived as acts of censorship on much needed dialogue 84.

Minister for Refugees, Immigration and Integration Affairs of the time, Rikke Hvilshøj, was one of the officials behind the call to exclude these Muslim leaders from integration dialogue in Denmark. She argued that they were knowingly trying to arouse anti-Danish sentiment in the Muslim world. On February 8, 2006, he told the Berlingske Tidende newspaper, “I think we have a clear picture today that it’s not [these] imams we should be placing our trust in if we want integration in Denmark to work.”

Jyllands-Posten editor offered a similar explanation when he chose to hold a contest for Muhammad cartoons. He was responding to demands by the Muslim community for more balanced and/or positive reporting on Islam and to recent decision by European theaters and art galleries to cancel potentially controversial exhibits and performances 85. He felt that Muslim objections to negative coverage and threats of violence amounted to censorship and limitations on freedom of speech: “This is a popular trick of totalitarian movements: Label any critique of call for debate as an insult and punish the offenders” 86.

The statements of Samha, Hvilshøj and Rose’s have similarities: each of these individuals are trying to influence how practical issues related to Islam and Muslims are approached (such as press coverage, artistic expression, conflict resolution), which actors are recognized as legitimate negotiating partners in discussion, and how integrated Danish Muslims should act. Rose and Samha also directly speak of fears that censorship stands in the way of constructive dialogue, although they disagree on the sources of this censorship.

Danish Muslims are not the only Danes who object to Rose and Hvilshøj’s conservative positions. In the Danish Parliament, Minister Hvilshoj’s calls for deportation were rejected by the ruling coalition. According to Britta Holberg of the ruling Liberal party in the naturalization committee “We are in no position to revoke someone’s citizenship.” She added, “I cannot punish someone just because s/he thinks differently and it is ridiculous at the first place to grant them Danish citizenship and them revoke it.” Simon Emil Ammitzbøll, at the time representative of the Social Liberal Party, also said the call was an attack on free speech and that individuals’ citizenship should not be subject to political motivations, “It makes no sense to reconsider the citizenship of someone because some politicians are not pleased with his/her opinions; otherwise, everyone in this society will really watch their words from now on for fear that their citizenship could be revoked.”

In early February 2006, civic organizations emerged to critique anti-immigration conservative attacks. One day after its February 9, 2006 launch, the webpage had collected 8,500 greetings and short messages from Danes. The website included a letter printed in Danish, Arabic, and English that “strongly condemns the actions of Jyllands-Posten that have offended Muslims around the world” and called for an apology from Jyllands-Posten editors. According to anotherdenmark.org spokesman Nicolai Lang, “If we want to break down prejudices on both sides, then it’s important to show that the majority of Danes aren’t hostile toward Islam, and that there are many of us who believe that we can live together with respect for each other’s culture and identity.”

Another site, Reconcliation Now (doesn’t exist anymore) was able to gather 36,000 electronic signatures in its first four days of existence. This electronic petition, designed by Dane Hans Hüttel, criticized the cartoons for showing “a serious lack of tact and sensitivity” and pointed to the distinction between “opinions expressed by a Danish newspaper and the opinions of the Danish people as a whole”.

In March 2008 a ‘Division for Cohesion and Prevention of Radicalization’ was established under the Ministry for Refugees, Immigrations and Integrations Affairs. The Division’s first task was to write a new plan of action for prevention of radicalization. When the plan of action was published in a hearing in the end of 2008 one of the focal points was dialogue with extremist groups such as Hizb ut-Tahrir. Minister for Welfare at the time, Karen Jespersen was very much against this and called the idea of dialogue with extremist groups “alarming” 87. At the other end of the spectrum the Minister for Refugees, Immigration and Integration Affairs, Birthe Rønn Hornbech, said that the ideas in the action plan fully followed what was agreed on in the Government Bill. Hornbech and Jespersen had a heavy debate about the idea of dialogue and the Prime Minister had to calm his two ministers down 88. The debate about whether the authorities should be having dialogues extremist groups in order to prevent radicalization is an ongoing debate in Denmark. The Secret Service has been having talks with extremist groups for some years now and especially Danish People’s Party keep questioning the expediency in these talks 89.

“Act No. 375 of 28 May 2003 on Danish courses for adult aliens.” NewToDenmark.dk Available online at: http://www.nyidanmark.dk/resources.ashx/Resources/Lovstof/Love/UK/danish_courses_act_375_28_may_2003.pdf retrieved 2 April, 2010

“Act on Ethnic Equal Treatment Danish Ministry of Refugee, Immigration and Integration Affairs, ref. no. 2002/5000-6 527717.” NewToDenmark.dk Available online at: http://www.nyidanmark.dk/NR/rdonlyres/E67D2D1B-5CAD-4036-AE73-36A3A23B87E5/0/act_ethnic_equal_treatment.pdf retrieved 2 April, 2010

“Alien (Consolidation) Act. Consolidation Act No. 945 of 1 September 2006” NewToDenmark.dk website Available online at: http://www.nyidanmark.dk/resources.ashx/Resources/Lovstof/Love/UK/aliens_act_945_eng.pdf retrieved 2 April, 2010

Andreassen, R. The Mass Media’s Construction of Gender, Race, Sexuality and Nationality. An Analysis of the Danish News Media’s Communication about Visible Minorities from 1971-2004. PhD dissertation, Dept. of History, University of Toronto, 2005.

Andersen, J., E. Larsen and I. H. Moeller (2006). Exclusion and Marginalisation of Ethnic Minorities in the Danish Welfare Society – Dilemmas and Challenges. paper prepared for the XVI ISA World Congress of Sociology, RC 19. Durban, South Africa, 23-29 July 2006.

Boerresen, S. K. Fremmedhed og praksis – om tyrkiske og pakistanske indvandreres bosætning og boligvalg (Foreignness and practice – the Turkish and Pakistani immigrants’ settlement patterns and the choice of housing). PhD dissertation, Dept. of Sociology, Copenhagen University, 2000.

“Consolidation of the Act on Integration of Aliens in Denmark(the Integration Act). Consolidation Act No. 643 of 28 June 2001.” NewToDenmark.dk

Dahl, K. M., & V. Jacobsen. Køn, etnicitet og barrierer for integration. Fokus på uddannelse, arbejde og familieliv (Gender, ethnicity and barriers for integration. Focus on education, work and family life) The Danish National Institute for Social Research (SFI), 2005.

“Danish Consolidation Act No. 945 of 1 September 2006” NewToDenmark.dk.

“Debates and votes: Cartoons controversy: respect freedom of expression and religious beliefs, say MEPs”

Strasbourg Plenary (13-16 February 2006). Available online at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/expert/background_page/008-5223-047-02-07-901-20060209BKG05095-16-02-2006-2006-false/default_p001c004_en.htm retrieved 2 April, 2010

“Decision on Possible criminal proceedings in the case of Jyllands-Posten’s Article “The Face of Muhammed”” The Director of Public Prosecutions. 15 March 2006. Available online at: http://www.rigsadvokaten.dk/media/bilag/afgorelse_engelsk.pdf retrieved 2 April, 2010

“Denmark.” US Dept of State. International Religious Freedom Report 2004. Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

European Commission on Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) The 2nd Country Report on Denmark. ECRI, Strasburg, 2000.

European Commission on Racism and Intolerance (ECRI). The 3rd Country Report on Denmark. ECRI, Strasburg, 2006.

European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia. Muslims in the EU: Discrimination and Islamophobia. 2006.

European Parliament “Islam in the European Union: What’s at Stake in the Future” Policy Department, Structural and Cohesion Policies (May 2007).

“Executive Order on Aliens’ Access to Denmark (Aliens Order). 943 of 5 October 2005.” Bekendtgørelse nr. Available online at: http://www.nyidanmark.dk/resources.ashx/Resources/Lovstof/Love/UK/udlaendingebktg_943_eng.pdf retrieved 2 April, 2010

Feldt, J. and P. Seeberg. “New Media in the Middle East – an introduction” University of Southern Denmark. In New Media in the Middle East Working Paper Series No. 7:17. Centre for Contemporary Middle East Studies (2006).

“Freedom of religion and religious communities in Denmark.” The Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs (May 2006). Available online at: http://www.km.dk/fileadmin/share/Trossamfund/Freedom_of_religion.pdf retrieved 2 April, 2010

Geertz, A.W. and M. Rothstein. “Religious Minorities and New Religious Movements in Denmark” Nova Religio 4.2 (April 2001): 300.

Ghosh, F. Minoritetssocialrådgivere i et majoritetssamfund (Minority social workers in a

majority environment). The Association of Social Workers in Denmark, 2000.

Haarder, B. “Denmark and Islam: Facts and Fiction.” Office of the Minister for Education and Minister for Ecclesiastical Affairs, Denmark (February 27, 2006). Available online at: http://www.km.dk/497.html retrieved 2 April, 2010

Hervik, P. (ed). Den Generende Forskellighed. Danske svar på den stigende multikulturalisme (The Annoying Diversity: the Danish response to increasing multiculturalism). Copenhagen: Hans Reitzels Publishers, 1999.

Hervik, P. “Det danske fjendebillede” (“The Danish image of an enemy”). In Islam i bevægelse (The dynamics in Islam (alternatively) Islam under transformation). Eds. M. Shiekh et al. Copenhagen: Academic Publishers, 2003.

Hervik, P., and R. E. Jørgensen (2002). “Danske benægtelse af racisme” (“The Danish denial of racism”) in Dansk sociologi I Dag (Journal of the Norwegian Sociological Association) 4 (2002).

Hjarnø, J., & T. Bager. Diskriminering af unge med indvandrerbaggrund ved jobsøgning

(Discrimination of young applicants with immigrant backgrounds during job applications). Research Paper 21. Esbjerg: DAMES, 1997.

Hussain, M. “Denmark.” In Racism and Cultural Diversity in the Mass Media. An Overview of Research and Examples of Good Practice in the EU Member States, 1995-2000. Ed. J. Ter Wal. European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC), Vienna, 2002.

Hussain, M. “Islam, Media and Minorities in Denmark.” Current Sociology 48.4. Special Issue on the Muslim Family in Europe, October, 2000. 95-116.

Hussain, M. “Media Representation of Ethnicity and the Institutional Discourse.” In Media, Minorities and the Multicultural Society. Ed. T. Tufte. The Nordic Association of Communication Researchers (NORDICOM): Gothenburg University, 2003.

Hussain, M., et al. Medierne, minoriteterne og majoriteten – en undersøgelse af nyhedsmedier og den folkelige diskurs (The media, minorities and the majority – an investigation of the news media and the public discourse). Board for Ethnic Equality, Copenhagen, 1997.

“Intolerance and Discrimination against Muslims in the EU: Developments since September 11.” International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights (IHF) (March 2005). Available online at: http://www.ihf-hr.org/viewbinary/viewdocument.php?doc_id=6237 retrieved 2 April, 2010

Jagd, C. B. Breaking the Pattern of Unemployment through Social Networks. Paper presented at the 13th Nordic Migration Conference, November 18-20, 2004.

Klausen, J. The Cartoons that shook the World, Yale University Press, 2009

Koch-Nielsen, I., and I. Christiansen. Effekten af den boligsociale indsats over for indvandrere og flygtninge (Effects of social policy in the housing sector on the situation of the immigrants and refugees). AMID Working Paper Series 16. Aalborg: Aalborg University, 2002.

Kühle, L: Moskeer i Danmark – islam og muslimske bedesteder (Mosques in Denmark – Islam and Muslim places of worship), Forlaget Univers, 2006

Mikkelsen, F. Integrations Paradoks (The Paradox of Integration). Copenhagen: Catinét, 2001.

Mikkelsen, F. (ed.), Indvandrerorganisationer i Norden (Immigrants Organizations in Scandinavia) Nordisk Ministerråd, Akademiet for migrationsstudier i Danmark, Nord 2003:11

Mikkelsen, F., Indvandring og Integration (Immigration and Integration), Akademisk Forlag, 2008

Ministry of Integration Aarbog om Udlændinge (Yearbook on Foreigners). Copenhagen, 2005. Available at: www.inm.dk retrieved 2 April, 2010

Ministry for Refugees, Immigrants and Integrations Affairs, Integrationsforskningen i Danmark 1980-2002 (Integration Research in Denmark 1980-2002). Ministry for Refugees, Immigrants and Integrations Affairs, Copenhagen, 2002.

Ministry for Refugees, Immigrants and Integrations Affairs, Udvikling i udlændinges integration i det danske samfund (Trends and development in the integration of foreigners in Denmark). Ministry for Refugees, Immigrants and Integrations Affairs, Think Tank Report. Copenhagen, 2006.

Ministry for Refugees, Immigrants and Integration Affairs, Tal og fakta – befolkningsstatistik om indvandrere og efterkommere (Facts and figures – statistics on first and second generation immigrants), July 2009. Available online at: http://www.nyidanmark.dk/NR/rdonlyres/1515B0D4-92A1-451F-905C-8AC5A595C9EB/0/tal_fakta_juni2009_revideret_090709.pdf retrieved 13 February 2010

Ministry for Refugees, Immigrants and Integration Affairs, Tal og fakta – Indvandrere og efterkommeres tilknytning til arbejdsmarkedet og uddannelsessystemet (Facts and figures – First and second generations immigrants’ association with the labor market and system education), December 2009. Available online at: http://www.nyidanmark.dk/NR/rdonlyres/BA42D1B3-8F3C-4288-B9EB-42716FA5C13B/0/tal_fakta_dec_2009.pdf retrieved 13 February, 2010

Møller, B., & L. Togeby. Oplevet Diskrimination (The Experienced Discrimination). Board for Ethnic Equality. Copenhagen, 1999.

Nusche, Deborah, Wurzburg, Gregory & Naughton, Breda (2010): OECD of Migrant Education, Denmark, March 2010, available online at: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/54/17/44855206.pdf retrieved 30 March 2010

Open Society Institute, European Union Monitoring and Advocacy Program. Muslims in the EU. Cities Report. Denmark, 2007. Available online at: http://www.soros.org/initiatives/home/articles_publications/publications/museucities_20080101/museucitiesden_20080101.pdf retrieved 2 April, 2010

Open Society Institute, Muslims in Europe – A report on 11 EU cities. Available online at: http://www.soros.org/initiatives/home/articles_publications/publications/muslims-europe-20091215/a-muslims-europe-20100302.pdf retrieved 2 April, 2010