Germany has gone to the polls – and the results have thoroughly shaken the country’s political scene. The impression, prevailing at times in sections of the liberal international media, of Germany as a beacon of stability in a Western world marred by the rise of populism had for a long time been a faulty one. The election results of September 24th should finally dispel this myth.

A diminished Chancellor

To be sure, Mrs. Merkel will most likely remain Chancellor for a fourth term. Yet after her CDU/CSU party obtained only 32.9 per cent of the popular vote – its worst score since 1949 – many are expecting her to step down and make way for a successor before the next scheduled elections in 2021.1

Not only the CDU/CSU took a drubbing, however – the Social Democrats (SPD), Merkel’s junior partner in the outgoing coalition government, also suffered heavy losses. In what amounted to the SPD’s fourth electoral defeat since its ousting from the chancellery in 2005, the party only took 20.5 per cent of the vote – the worst results of the post-war era.

‘Jamaica’ coalition at odds on immigration, Islam

With the SPD immediately declaring that it would not join another Merkel-led coalition government, the Chancellor is now faced with the unenviable task of having to piece together a new government made up of her CDU/CSU party, the Greens, and the Free Democrats (FDP).

Whilst this coalition is gaily referred to as the “Jamaica” option because of the black, green, and yellow colours of its composite parties, reaching an agreement between conservatives, liberals, and ecologists will be anything but easy.

Not least with respect to questions of immigration, integration, identity, and Islam the three parties espoused strongly diverging positions throughout the electoral campaign. These differences are likely to harden now: the conservative wing of the CDU/CSU is attributing the severe losses of the election night to an insufficiently conservative profile. Long-standing critics of Merkel’s centrist course announced immediately after the publication of the first exit polls that they would seek to “close the party’s right flank”.2

Ending Germany’s anti-populist ‘exceptionalism’

This ‘right flank’ had fallen prey to the large-scale electoral gains of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party. The AfD had started as an anti-Euro movement; it centred on dissatisfaction with what it perceived as an overly concessionary stance on Mrs. Merkel’s part towards Greece and other southern European countries during the Eurozone crisis.

Yet the group quickly took on an anti-immigration line, particularly since the arrival of several hundred thousand refugees in 2015. Ever since, it has developed a staunchly Islamophobic profile and relied upon the calculated breaking of taboos in order to gain attention. Leading party functionaries have strong ties to the Pegida movement, as well as to the neo-Nazi scene.3

After scoring 12.6 per cent of the popular vote on September 24th, leading AfD politician Alexander Gauland announced to overjoyed supporters that this was the first step to “taking back our country and our people”. This statement built not only on the widespread populist slogan of ‘taking back control’, so widespread for instance in Brexit Britain. It also retained the völkisch-nationalistic tone of the AfD’s election campaign.4

“What is wrong with this country?”

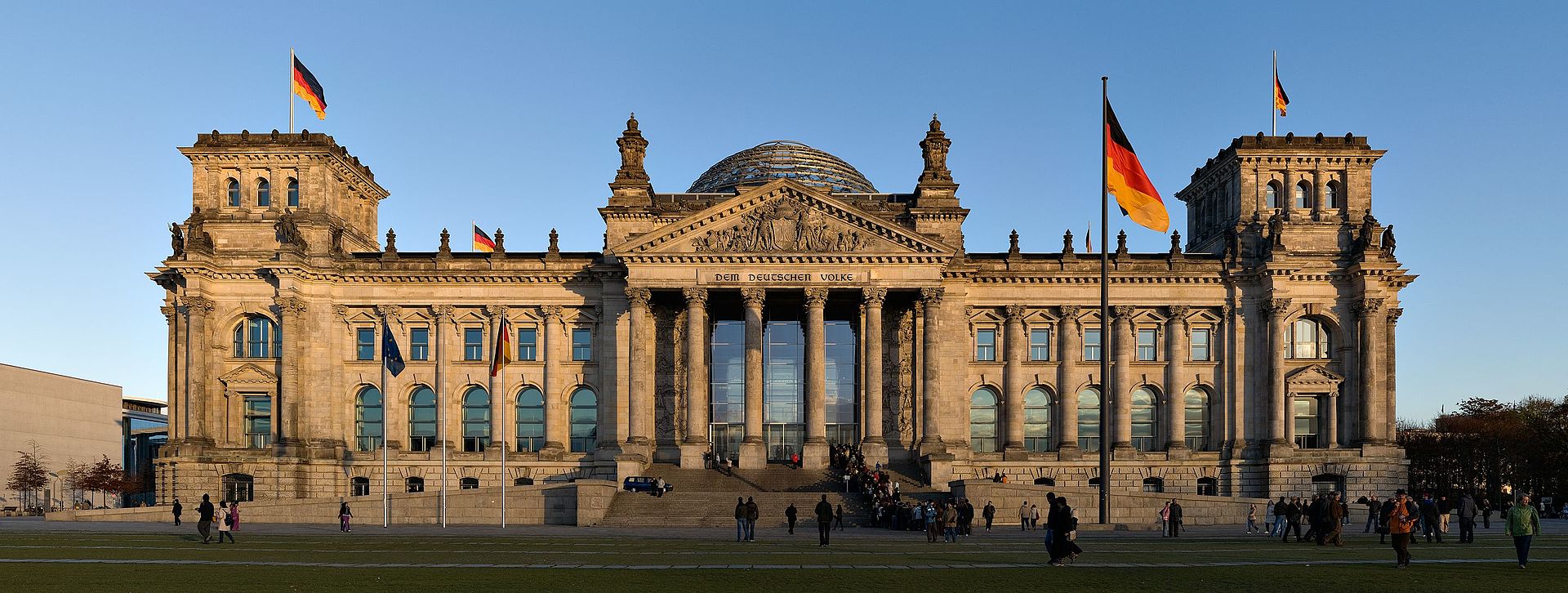

The AfD thus emerged as the biggest winner of the election night by far: in 2013, the party had failed to take the five-percent-threshold below which parties do not obtain any parliamentary seats. Whilst it had been expected that the AfD would make it into the Bundestag – and thus constitute the first far-right party to enter the national parliament since 1961 – the populists’ strong showing was nevertheless met with shock by German Muslims.

Many took to Twitter to express their incredulity: lawyer Serkan Kirli asked “What is wrong with this country?”5 And renowned journalist Hakan Tanrıverdi felt like he “had been made a foreigner” by the millions who voted AfD.6

Religious leaders’ reactions

Religious leaders from Christian, Jewish, and Muslim groups have expressed their concerns over the AfD’s entrance to parliament. Many Christian leaders stressed that the party’s positions were irreconcilably opposed to the fundamentals of the Christian faith.7

Among the initial Muslim voices, the most widespread fear has been that the established parties might adopt the AfD’s far-right positions in an attempt to regain the trust of the populists’ electorate. Burhan Kesici, leader of the Islamic Council of Germany (IRD), voiced the expectation that “not a single Islamophobic or xenophobic statement be tolerated in the Bundestag”8

Muslim representatives demand AfD’s ostracism

The Islamic Community Milli Görüş (IGMG) stated that “we expect a clear demarcation against the AfD’s positions”9; a sentiment echoed by Aiman Mazyek, chairman of the Central Council of Muslims in Germany (ZMD). For even if the other parties should make the AfD’s suggestions their own, “in the end”, Mazyek asserted, “voters will not vote for the copy but the original”.10

Non-denominational organisations, such as those representing ethnic Turks in society and in politics, have taken a similar stance. For the Turkish Union in Berlin and Brandenburg (TBB), “the democratic parties are now called upon not to seek any cooperation with the AfD and to refrain from making any AfD positions their own.”11

Approach towards AfD and its voter base unclear

What continues to be unclear from the formal statements of German Muslim figures, as well as from the post-election utterances of the mainstream parties, however, is how democratic forces should actually engage with the AfD and its sympathisers.

To many observers – Muslim or other – the desired ‘clear demarcation’ against the AfD amounts to de facto ignoring the populists. Yet it is not only that the AfD managed to gain millions of votes: judging from the party’s behaviour so far, its spite and disregard for democratic rules will simply be difficult to ignore in the Bundestag.

In a post-election opinion piece for the Tagesspiegel newspaper, Aiman Mazyek consequently noted that merely ‘ignoring’ the party would not do: “We should precisely not ignore [the AfD] but rather take on the controversial debate and lead it in the light of the defence of freedom and human rights”. What this might mean in practice remains of course to be seen.12

Explaining the AfD’s rise

In any case, the night of the election was less dominated by a discussion of how to deal with the AfD in the future Bundestag than by the attempt to make sense of its electoral success. Scrutinising the role of the media, ZMD chairman Mazyek highlighted the ways in which populists had managed to set the political agenda through their dominance of airtime.13

In particular, he criticised the TV duel, which had focused overwhelmingly on issues of migration, integration and Islam, and in which suggestions that migrants were dangerous scum wishing to drain the German welfare state and upend the country’s social order went unchallenged.

A deeper process

Yet whilst the media circus obviously boosted the AfD’s taboo-breaking messages by giving them a disproportionate share of the broadcasting time, the roots of right-wing populism in Germany are much deeper than suggested by a mere focus on skewed pre-election media reporting.

The arrival of the AfD in the federal parliament only renders visible what had previously remained hidden under the surface (or, perhaps more accurately, been swept under the rug). On September 24th, mainstream observers and politicians alike were finally made to take note of the fact that a non-negligible part of the country no longer shares the very basics of the political consensus.

“Why did you vote AfD?”

In a sign of its befuddlement, the socially liberal Die Zeit newspaper asked “Why did you vote AfD?” and asked readers to describe their electoral motives in the comment section. The paper received hundreds of answers. These are of course not statistically representative; they are nevertheless illustrative of the parallel universe of xenophobia, Islamophobia, and paranoia many AfD voters live in.14

Responding to the Zeit’s question, one women commented that “I have voted for the AfD because I have thoroughly studied the Qur’an and the hadiths; terms such as ‘abrogation’ or ‘taquiyya’ [misspelling of the Arabic term original] are more than familiar to me.”

She went on to name the most trusted sources for her supposedly authoritative understanding of Islam. Pride of place was accorded to the right-wing blogs of ‘intellectuals’ such as Henryk M. Broder and Roland Tichy, both of which regularly pedal in conspiracy theories and anti-Muslim hatred.

‘Critics of Islam’

She also mentioned a barrage of books on the ‘Islamic danger’ that have often dominated Germany’s best-seller lists over the last few years. Authors include Hamed Abdel-Samad, Abdel Hakim Ourghi, Bassam Tibi, Zana Ramadani, or internationally-known Ayaan Hirsi Ali.

Authors and activists such as Seyran Ateş and Ahmad Mansour also had the dubious honour of being included on her list. This shows the unfortunate development in which politically conservative voices get co-opted into the worldview of the radical right – even if they seek to avoid it and even if they might offer an understanding of issues such as jihadism that is at least in parts more nuanced.

A parallel discursive universe

All of these seemingly legitimate voices have created a far-right universe of immense depth. AfD sympathisers can move within this segregated sphere of ‘alternative facts’ without ever being confronted with diverging statements – or with a Muslim, for that matter: once more, support for the AfD was strongest in areas with the lowest number of immigrants.15

Consequently, the AfD’s stronghold continues to be the territories of the former GDR, where it obtained 21.5 per cent of the popular vote. In the state of Saxony, home of the Pegida movement and the site of some of the most vitriolic anti-Muslim and anti-establishment hatred, the AfD emerged as the largest party, outdoing even the CDU in its former heartland.

In a somewhat ironical take on the election results, Green Party politician Belit Onay noted that it was therefore not Muslim immigrants who had created ‘parallel societies’ in Germany – a supposed development often presented as proof of insufficient integration. Instead, he argued, the true ‘parallel society’ existed in the AfD milieus of the East.16

“Anxious citizens” and their fear of Islam

Many Muslims have also taken offence at mainstream politicians’ insistence – both before and after the election – that they would ‘take seriously’ the fears and worries of the AfD electorate. In a euphemistic turn of phrase, Pegida marchers and populist supporters have become known in Germany as ‘anxious citizens’ (besorgte Bürger).

This term connotes a predominantly but not uniquely Eastern swathe of the electorate that is in part hard-pressed by socio-economic conditions, yet whose overall fearfulness is squarely directed at cultural change associated with immigration.

According to statistics published by the ARD public broadcaster, 95 per cent of AfD voters feared “the loss of German culture and language”, and 92 per cent were afraid of “the influence of Islam in Germany”.17 This resonates with previous studies, in which 40 per cent of German respondents believed that the country was being ‘infiltrated’ by Islam.

Minorities not present during the campaign

In a piece titled “Here is an anxious citizen speaking”, journalist and activist Ferda Ataman castigated the fact that all parties rushed to embrace and legitimise the fears of the AfD electorate. Conversely, she observed, “no one spoke of the anxieties of Muslim, Jewish, or homosexual voters” in the face of the AfD’s rise.

In fact, she asserted, the voice of these minorities had been almost completely absent during the campaign, ensuring that everybody talked about them but that they were never at the table. In this way, racist, xenophobic, and sexist claims were never effectively contested in public.18

Pushing back against populism

Some hope that such contestation will take place now, and that the arrival of the AfD in the Bundestag will reinvigorate civil society activism – especially among those groups most targeted by the AfD’s programme. Christian religious leaders have already urged their community members to step up against nationalism, xenophobia, and racism, and to become politically active.19

The Liberal Islamic Union (LIB), a small group of self-definedly ‘progressive’ Muslims, wrote in a Facebook post that the LIB was now “confronted with an important task: to continue to work together for an open and tolerant society, in which everybody has his or her space.”20

Many existing Muslim civil society initiatives will also take the election result as a call to action: Ozan Keskinkılıç, one of the co-founders of the Berlin-based “Salaam-Shalom” initiative for Jewish-Muslim dialogue, emphasised his willingness to take up the fight with the surging forces of populism: when asked whether he was contemplating emigration from Germany, he vowed “I stay and thereby I resist”.21

Limited organisational footprint

It would surely be a most welcome development if the AfD’s success at the ballot box should lead to increased Muslim engagement in society and in politics. At the same time, financial and organisational resources of many Muslim initiatives continue to be exceedingly limited, and the political climate is likely to worsen in the coming years.

Against this backdrop, some think that the best hope for Germany’s Muslim community is the potential breakup of the AfD amidst infighting between its national-conservative and quasi-fascist factions. Indeed, the party’s short history has been thoroughly marked by infighting. Although these disputes have shifted the party to the right countinously, some observers expect the party to lose popular appeal as it becomes ever more radical.22

Waiting for the AfD’s break-up?

Indeed, on the morning after the vote, AfD leader Frauke Petry (who had just been elected to the Bundestag) announced that she would not join her party’s parliamentary group. For months, Petry had wished to take her party on a firmly ethnonationalist yet parliamentary course, with the ultimate aim of forming a coalition with the CDU/CSU.

Her party base thoroughly rejected her ‘moderate’ stance, however, opting instead for an opening to the neo-Nazi flank and a more rabble-rousing style. Following Petry’s departure from the parliamentary group, leading counter-terrorism expert Peter Neumann commented sardonically: “The AfD is radicalising itself through successive schisms. Social scientists know such processes from terrorist organisations as well.”23

Waiting for the AfD’s self-destruction nevertheless seems a risky gamble. Not only is the implosion of the populists not a foregone conclusion; even if it did happen, they might still manage to do severe harm to German democracy in the process.

Sources

http://www.stuttgarter-zeitung.de/inhalt.kanzlerdaemmerung-in-berlin-wie-lange-bleibt-merkel-noch-kanzlerin.a322c77d-9fc8-4cff-9792-3569fd3cff5a.html ↩

http://www.fr.de/politik/bundestagswahl/nach-der-wahl-seehofer-will-die-rechte-flanke-schliessen-a-1357158 ↩

http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/neue-abgeordnete-das-sind-die-radikalen-in-der-afd-fraktion/20361302.html ↩

http://www.deutschlandfunk.de/bundestagswahl-gauland-afd-wird-die-bundesregierung-jagen.1939.de.html?drn:news_id=795978 ↩

https://twitter.com/RA_SerkanKirli/status/912216210045128704 ↩

https://www.domradio.de/themen/kirche-und-politik/2017-09-25/religionsvertreter-zu-den-ergebnissen-der-bundestagswahl ↩

http://islamrat.de/kesici-zum-wahlausgang-wir-alle-tragen-eine-historische-verantwortung/ ↩

http://islamrat.de/kesici-zum-wahlausgang-wir-alle-tragen-eine-historische-verantwortung/ ↩

http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/gastkommentar-des-zentralrats-der-muslime-was-wir-im-umgang-mit-der-afd-falsch-gemacht-haben/20370900.html ↩

http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/gastkommentar-des-zentralrats-der-muslime-was-wir-im-umgang-mit-der-afd-falsch-gemacht-haben/20370900.html ↩

http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/gastkommentar-des-zentralrats-der-muslime-was-wir-im-umgang-mit-der-afd-falsch-gemacht-haben/20370900.html ↩

http://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2017-09/wahlentscheidung-warum-afd-gewaehlt ↩

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/afd-im-bundestag-hier-spricht-eine-besorgte-buergerin-kommentar-a-1169716.html ↩

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/afd-im-bundestag-hier-spricht-eine-besorgte-buergerin-kommentar-a-1169716.html ↩

https://www.domradio.de/themen/kirche-und-politik/2017-09-25/religionsvertreter-zu-den-ergebnissen-der-bundestagswahl ↩

https://www.facebook.com/liberalislamischerbund/posts/1487350311300459 ↩

https://twitter.com/ozankeskinkilic/status/912012221026271232 ↩

http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/demoskop-richard-hilmer-zu-afd-das-geht-bis-tief-in-die-mittelschicht-hinein/13318392.html ↩

https://twitter.com/PeterRNeumann/status/912270720440373249 ↩