Introduction

In July 2022 the report “Discrimination, Prejudice and Cohesion – Intergroup relations among Black, Muslim and White People in Britain in the Context of Covid-19 and Beyond” was published as part of the Beyond Us and Them project, “a series of national and sub-national surveys examining perceptions and experiences of social cohesion across Britain between May 2020 and July 2021”1. The report aims to better understand and to compare the attitudes held towards, Black, Muslim and White people in the UK during the pandemic by drawing surveys data on prejudice, experiences of discrimination and intergroup contact2. It is a collaborative endeavour, authored by Dominic Abrams Fanny Lalot and Hilal Ozkeçeci, (Centre for the Study of Group Processes, University of Kent), and Jo Broadwood, Kaya Davies Hayon and Andy Dixon (Belong – The Cohesion and Integration Network, a charity and membership organisation with the belief in a more integrated, less divided society).

Methodology

To answer the central question “how are relationships between individuals, communities and society adapting and reshaping in the face of this pandemic?”3, the authors used a combination of focus groups, structured interviews, and online surveys (through the Qualtrics survey platform) across the UK. Between May 2020 and June 2021, 39,000 responses were collected through a series of eight online surveys4. The authors stipulated that a the survey was addressed to specific areas, places, and/or types of people, rather than opting for a single national survey5. Regarding areas and places, surveys were first directed to people living within different parts of the UK (Scotland, Wales and one part of England – Kent), then a further six samples were collected from the following local authorities in England: Blackburn with Darwen, Bradford, Calderdale, Peterborough, Walsall and Waltham Forest)6. These areas were selected because they had prioritised social cohesion by implementing programes in response to different local integration and cohesion challenges. For example, Bradford’s “Stronger Communities Partnership Initiative (2018-2023)” aimed to make Bradford a place where everyone feels they belong, are understood, feel safe and can participate in civic life7, and Walsall’s (2019) “Our vision for integrated and welcoming communities” sought to create empowered, inclusive communities where people from different backgrounds can come together and celebrate what they have in common8.From December 2020 until June 2021, surveys were added in Greater London, West Midlands, Greater Manchester, and the West of England. To ensure there was quota samples large enough to capture experiences reliably, the authors over sampled people who are Muslim and Black9.

61 Focus groups and 256 one-to-one semi structured interviews were then conducted in all sampling areas9. The four primary interviewers were women, from different ethnic backgrounds, with one identifying as having a disability10.

The report focuses primarily on attitudes towards and experiences of Black and Muslim people in the UK. The authors also acknowledge the disproportional impact of Covid-19 for these groups and the absence of large-scale research which focuses on Black and Muslim people’s experiences of the pandemic. With ethnic differences in mortality and hospitalisation for Covid-19 rising, increased awareness of racial discrimination following the murder of George Floyd, and stigmatisation and scapegoating being regularly reported11, attention needed to be paid to “assessing impacts on the perceptions and self-perceptions of Black and Muslim people in response to both media coverage and government actions”12.

Key Findings

- Perceptions of division and unity between different social groups

In contrast to the build-up to the 2019 UK General Election, the report notes that by May 2020 (two months after the beginning of the first national lockdown) “there was a strong sense of cross-national unity, and this perception was consensually shared across all social groups”13. Divisions between groups emerged in the Summer of 2020, where “at least a third of respondents perceived groups based on age, nationality, or ethnicity as being in opposition or strong opposition to other groups in society”14. When breaking this down by race and religion, key findings show that:

a. Perceptions that Muslim people are opposed to others in the UK is 10% < higher among White respondents (46.9%) and Black respondents (47.7%) than Muslim respondents (35.1%)15. Muslim respondents are also more than twice as likely to perceive Muslims as being united with other groups in the UK (29.9%) than White respondents (12.1%)16.

b. Over 40% of Muslim, White and Black respondents report that Black people are opposed, rather than united with, other groups in the UK17.

c. More than 8% of Muslim respondents perceive younger people in the UK as being typically more united with older people, than Black or White respondents. Although over 35% of all respondent groups still perceive different generational groups to be in opposition18.

Taken these findings all together they show that Muslim respondents are more likely to perceive unity between different generations, Muslim groups and Black groups that other respondents, and more than a third of all respondents perceive Black and Muslim people to be in opposition to others19.

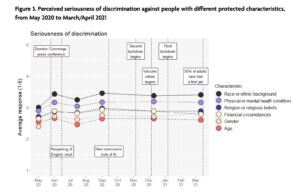

- Perceptions of discrimination as a serious issue

Finding two explores the severity of discrimination amongst and between groups by asking “how serious do you think the issue of discrimination against people is, because of: (people’s age, race or ethnic background, religion or religious beliefs, presence of physical or mental health condition, and financial circumstances”20. Answers ranged on a scale of 1 (Not at all serious) to 5 (Extremely serious). The perception of severity changed during data collection, with an increase in perception of seriousness of discrimination following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. Perceived seriousness also increased for all protected characteristics from June 2020. Authors also found this increase in their qualitative analysis with respondents commenting on the higher Covid-19 mortality rates for ethnic minority groups21.

When analysing the statistics by protected characteristic for each respondent group the authors found the following:

a. As shown in the figure below, discrimination based on ethnicity/race is perceived as the most serious, with age being the least serious22.

b. All respondents regard discrimination based on ethnicity/race to be above 3 on the 1-5 scale, with Black respondents regarding discrimination on ethnicity/race to be more serious than any other respondent group23.

c. Muslim respondents regard discrimination based on religion to be more serious than Black respondents, who in turn regard it as being more serious than White respondents24.

d. Women, across Black, Muslim and White respondent groups regard discrimination based on race, religion, and gender as being more serious than their male counterparts25.

e. Black respondents are more likely to rate gender discrimination as serious. Regarding Muslim and White respondents on the topic of gender discrimination, Muslim women are more likely to rate gender discrimination as serious than White women, but White men perceive gender discrimination as more serious than Muslim men26.

These findings are indicative of “cumulative rather than multiplicative effects of belonging the multiple groups that face discrimination”27. As shown in finding 2E, respondents do not generalise the sense of seriousness against their own group to their perception of seriousness of discrimination towards others. The authors further note that there seems to be some social of psychological obstacles to people’s perceptions across different groups and categories. In turn, this may make it more difficult to reach consensus on the overall impact of prejudice and discrimination and the policies required28.

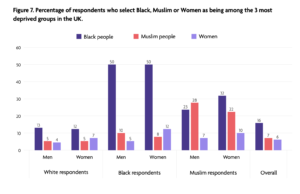

- Perceptions of deprivation

Focussing more on inequalities and vulnerabilities in relation to one’s economic status, respondents were asked in March-April 2021 which three groups they believe were currently the most deprived in the UK. A list of 31 groups were provided for respondents to choose from and included. Only 16% of respondents included Black people, 6.5% included Muslims and 6% included women in their top three, meaning Black people, Muslim people, and Women were ranged 5th, 14th and 15th out of the 31 groups29.

The results in the figure below from the report show that the acuteness of deprivation is perceived more acutely by those who are directly affected:

a. Half of all Black respondents perceive Black people as being deprived and a quarter of Muslim respondents perceive Muslims to face deprivation in the UK30.

b. White respondents are only a quarter likely to perceive Black or Muslim people as being deprived. Black and Muslim respondents are also only half as likely to see each other’s groups as deprived compared to their own31.

c. Across all respondent groups, women are at least a third more likely to consider women are more deprived in the UK than men32.

- Attitudes towards White, Black, and Muslim people

In this section of the report attitudes and emotions towards other social groups were measured through a “feeling thermometer”. Here, respondents had to indicate how “cold” or “warm” they feel towards a specific group33. The results from the survey show that attitudes towards Muslim people are consistently less favourable than all respondent groups, with the exception of migrants. However, “warmth of feeling” towards Muslim and Black people, and to a lesser extent migrants increased in June 2020, which the authors argue can “reflect the issue of racism being brought to wider public attention by the Black Lives Matter movement”34.

- Experiences of discrimination

The levels of discrimination reported by both Muslim and Black respondents was extremely high. 81% of Black and 73% of Muslim respondents, both male and female, reported having experienced some form of discrimination in the past month, in comparison to 53% of white people35. When breaking these statistics further by age and gender, 78% of respondents aged 18-24 reported facing discrimination in comparison to 44% of those aged 45<. Respondents who are younger, female, and Black and/or Muslim reported experiencing more discrimination than any other group. These findings highlight the intersection nature of discrimination that becomes cumulatively greater the more protected characteristics one has36.

- Intergroup contact between White, Black and Muslim people

The final finding focuses on intergroup contact with the authors acknowledging that “contact between members of different groups (under certain conditions) can help reduce prejudice and intergroup conflict”37. The researchers focused both on contact in person and on social media, the quality of contact (positive/negative) and the quantity (frequency or number of people).

The results from the survey show that Muslim and Black respondents were more likely to have intergroup contact than White respondents, due to the demographics of the UK and distribution of ethnic minority people geographically38. Muslim and Black respondents were also more likely to have negative intergroup experiences than White respondents39.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The report concludes that these findings show how much more work is required if the UK is to ensure equality of treatment and inclusion across ethnicity, religion, gender, age, and other protected characteristics. The authors offer three primary recommendations: to give greater urgency and commitment to tackling discrimination, to strengthen policies and initiatives that build connections between groups, and to foster public spaces and forms of dialogue between different groups across society40.

Sources

https://www.belongnetwork.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Belong_IntergroupRelations_Report_V3.pdf

https://www.belongnetwork.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Belong_SocietalCohesion_Report_V5.pdf