The 8th June 2022 saw the release of a new U.S. TV show “Ms Marvel”, created by British-Pakistani stand-up comedian and screenwriter, Bisha K. Ali. The show follows Kamala Khan, a Pakistani-American teenager who transforms into a superhero whilst grappling with familial and religious obligations1. This makes Khan the first Muslim superheroine of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and one of the most successful Marvel characters of the last decade. Despite some criticisms of the show, according to the New Arab “Ms Marvel should mark a dramatic shift for the future of Muslims in popular media”2 that comes at a time when Hollywood “continues to largely depict Muslim characters as targets or perpetrators of violence”3.

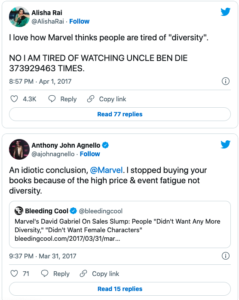

In 2013, Marvel announced they were reimagining the comic book character of Ms. Marvel, from a white blonde woman to a Pakistani Muslim teenager, which was “considered a controversial and risky proposition”4. Marvel’s vice president of sales, David Gabriel, in 2017, stated that feedback from retailers indicated that “people didn’t want anymore diversity […] they didn’t want female characters out there”5. Yet, upon publication, Ms. Marvel became one of the biggest selling comics online, and by 2018 had sold more than half a million paperbacks6. According to Dr Mel Gibson (associate professor at Northumbria University) it attracted “non-traditional comic-book readers – such as females, Muslims or Pakistani Americans for example. It helped draw in new folk and diversify the fan base”7. Writer of the Ms. Marvel comic book series, G. Willow Wilson (also a white American convert to Islam), responded to Gabriel’s comments that “the reason Ms Marvel has struck a chord it has is because it deals with the role of traditionalist faith in the context of social justice, and there was – apparently – an untapped audience of people from a wide variety of faith backgrounds who were eager for a story like this”8.

The head writer of the show Bisha K. Ali states that she used her own experiences as a second-generation writer and growing up as the child of Pakistani-born parents in England9. Whilst the show has been written for the broad Marvel audience, Ali says it particularly speaks to people “who rarely get to see themselves be the protagonists, who have suffered from a history of poor media representation in the West”10. She added it has been a joy “hearing a lot of people from Pakistani backgrounds, and I think a lot of second-generation backgrounds especially, responding, being like ‘Yep, I’ve had this word-for-word dialogue with my parents. It’s like you’re living inside my teenage living room”11. Ali does point out the show avoids common stereotypes of second-generation Muslims rejecting their community. There’s no glimpse of “these people, this culture oppresses me and I’m in direct conflict”12 with the community, Ali says. Instead, the show depicts important aspects of South Asian Muslim culture, with characters speaking a combination of Urdu and English, wearing South Asian dupatta’s when attending mosque, the soundtrack including a mixture of pop and desi tracks, and the feature of a South Asian wedding in Episode 813.

Other central themes in the show include the empowerment of the character Nakia by wearing the hijab, or the generational trauma of the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan. Concerning the latter, reviewers have commended the show for depicting the trauma with nuance and sensitivity14. Film industries in India and Pakistan predominantly portray the partition with anguish and sorrow. Ms. Marvel on the other hand, addresses it through the lens of the present which creates a multi-generational story of loss and, identity15. The history of the partition is shown through the storyline of how Kamala gains her powers; from a bangle that belonged to her great-grandmother Aisha, who disappeared during the partition. One of the show writers, Aanchal Malhotra, who has documented oral histories of the partition in her previous works, states “people carried heirlooms across the border and in the show, it’s literally a portal to the past […] for younger generations that don’t know anything about the cataclysmic events of 1947, an object can be a starting point” to understanding16. In the show, Kamala, is transported to the past, and the audience can hear the voices and conversations from oral histories recorded in two independent archives: the Citizen’s Archive of India and the Citizen’s Archive of Pakistan17.

About the hijab , Bisha K. Ali sought to depart from the dominant narratives that depict it as a tool of oppression. She writes “what felt really important was that this was a choice for her [Nakia]. She feels empowered by putting it on”18. Although Bisha does acknowledge that she is mindful she cannot represent every single Muslim experience on the show, she hopes that some young girls who have chosen to wear the hijab can see themselves and their choices in Nakia19.

However, Safiyya Hosein (Lecturer at Toronto Metropolitan University) has highlighted that whilst most Muslims welcome the show, some have been outraged by the revelation in Episode 3 that Kamala is a djinn (a Qur’anic term popularly understood as supernational beings)20. Filtered through a western orientalist lens, djinn has led to “genie” stereotypes and depictions21. Hosein notes that many Muslims have said it has been a surprising choice to draw on orientalist tropes for the first Marvel Muslim Supehero as a djinn.

Kristian Peterson (Assistant Professor in Philosophy and Religious Studies ad Old Dominion University) has written that what makes Ms. Marvel so authentic, is not just the on-screen representation but those behind the camera too. Ms Marvel is put together by a team of “writers, directors, as well as visual and musical artists who come from Muslim communities and cultures”22. It means they draw on their own lived experiences within their communities to tell genuine stories about Muslims. Peterson adds “Muslim storytellers are envisioning new powerful narratives about their lives and paving the way for future media makers”23 which, is the path to dismantling historically stereotypical portrayals of Muslims. “In the end representation of Muslims on screen is important but it also matters who is in the room to tell the story”24.

Sources

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-62117924

https://english.alaraby.co.uk/features/ms-marvels-creative-team-what-makes-it-special